It was the beginning of triathlon training season. As I slipped into the pool, I was trying to remind myself of what I knew. Stroke, stroke, stroke, breathe left. Stroke, stroke, stroke, breathe right. Pull the water. Keep your head down. Kick. Harder. After a mere 10 lengths in the pool, my arms were tired. How would I ever be able to swim a half-mile non-stop for the triathlon?

Although I asked the question, I knew the answer: by building my stamina. Ten lengths the first day is 12 lengths the next week which is 15 lengths the next and at that point I’m doing about a quarter-mile: halfway there. When I give myself plenty of time to train, the gains are small and appreciable. A month before the race, the day of 10-length sore arms is only a memory.

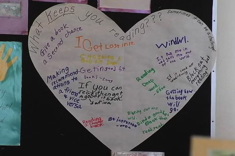

Students build stamina for writing in the same way. Stamina is defined as “staying power” or “toughness.” Often when we think of staying power related to writing, we think of the amount of time a writer generates at one particular sitting. Katie Wood Ray (author of many books including one of my favorites: Already Ready) talks about another kind of stamina – the staying power to come back to the same piece and pursue project-like work, connecting one day to the next.

A third kind of stamina highlights toughness. Every time we reread our work and doctor a word here and a phrase there – that is toughness. Every sentence we cut or move to its rightful place is hard work. Every ending we re-write is stamina too.

When it comes to writing stamina, these are the types that matter:

1. One-sitting staying power

2. Same project staying power

3. Toughness to revise

How Do Students Exhibit Stamina?

One-sitting staying power is the type of stamina I see most often taught in classrooms. Thanks to the work of many workshop models like The Daily Five that focus on teaching expectations through slow gradual release, teachers begin by expecting a shorter time-on-task initially, and increase the time expectation as students’ skills strengthen.

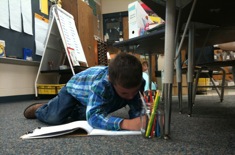

I got to see one-sitting staying power up close and personal in Linda Karamatic’s class, where second graders wrote for almost five minutes on the first day of school. And in March? Those same seven-year-olds wrote for over an hour as Linda and I taped individual conferring sessions with the Choice Literacy crew!

Another aspect of staying power is knowing when and how to take breaks. I just got up and took a brisk walk around my property because I’d been writing for about twenty minutes. After twenty minutes I find that if I get up stretch and move for a couple minutes, I can come back to my project with renewed energy and work for another twenty minutes or more. Often in those transitions, my good ideas flow. Kids can learn to take appropriate breaks to rest their hands, change position, or browse a book.

With the second type of stamina, consider: Do students know how to “pick up where they left off”? Some naturally understand project work, but many do not. Students are successful when they have an organized writing system to be able to locate their current project, followed by time to review what they were working on yesterday. Explicit strategies like “point and chat” with a partner buoy their connections to past work.

How Do We Model Stamina?

“Welcome back from recess everyone. I can see your pink cheeks. I’m glad you were running around. Yesterday in writing we started our literary nonfiction pieces. Turn to someone next to you and whisper the topic you are writing about. If you need to peek in your writing folder to remind yourself — that’s fine.”

The room is filled with whispered topics like “Tigers,” “Mango,” “Japan,” “Polar Bears” and more.

“I asked you to bring your writing folders down to the carpet because it can be difficult to know how to start after your first day of writing. Does everyone remember that I’m writing about rice noodles?”

I show my writing folder.

“I’m going to model with my partner, Felix, and I’m going to ‘point and chat’ for a minute to tell Felix what I’m working on. This will help remind me of where to start. Watch what I point to and listen to what I say, you can tell me after.”

“Okay Felix,” I say as I point to the notecards in the right hand pocket of my folder. “Yesterday I found 1 . . . 2 . . . 3 . . . facts about rice noodles and I have two more blank cards so I could start by finding more facts if I wanted.” Then I point to the lined paper, “I also started describing what happens to the dry rice noodles when they are put in warm water. I left off with the word ‘and’ [I point to the word] so I could keep writing about that because I haven’t told yet about how they get soft and slimy in the water. I think I’m more excited about the describing part right now, so I’ll whisper read what I’ve written so far and then add more.”

I pause as I ask, “What did you see me point and chat about?”

The kids recall me pointing to my facts cards and my lined paper. One student in the back says, “You pointed to your last word to help you remember.”

Then Felix models with his folder and points at his notecards, “I worked on facts all day yesterday about mango so I have 1 . . . 2 . . . 3 . . . 4 . . . 5 cards. I’m going to keep getting more facts today. I wrote down the website so I could go back there because it’s a really good one. When I get about three more, then I’m going to start on the story part about eating mango on my uncle’s farm in California. I have my notes on that right here.” He points.

“Now writers, turn to your partner and point and chat about what you were working on yesterday and what you may work on today.” The room is filled with words like facts, nonfiction, started, now, today, and write. We review what the voice level in the room will sound like and then I offer an invitation, “If you are unsure of what you are working on today, stay at the carpet for a moment.”

This day four writers stay. One was absent. Another is unsure if she should keep fact finding or transition to her literary part. A third isn’t liking his topic as much as he thought he would. The last just wants to show me what he’s got.

I don’t make assumptions that kids will know how to start back up with a project. I know I won’t need to model ‘point and chat’ every day, but right now they need the support. I also don’t assume that every student got what he/she needed during partner talk so I offer the flexible small group on the spot. Without that step, in my experience it’s sometimes been 5…10…even 15 minutes before I’ve found them struggling to get started.

What Happened? What’s Next?

One-sitting stamina and project staying power are essential skills for writers. For some, this writerly tenacity comes naturally, and for many others it needs to be modeled, taught, reinforced and celebrated. When I take teachers to observe in rooms of distinguished colleagues, they all comment on the students’ level of independence and their stamina. By April it looks like magic, but in the beginning it was a patient investment of intentional teaching.

I’m swimming comfortably in the pool now and soon it will be time for me to transition to the lake to prepare for my Seattle triathlon. The swim leg of the triathlon is often the most difficult for new triathletes. A half-mile may not seem daunting until you are in the water, swimming and swimming and swimming. I’m thankful I’ve had good friends and coaches to encourage me to build my stamina — it’s made all the difference. I’m not fast, but I finish.

Consider these questions:

- How long can your students currently sustain writing?

- What are some strategies you use to help students connect to projects and continue work?

- What does stamina look like in your writers? What do you want it to look like?