Powerful writing instruction allows time for students to practice. When we force a lockstep approach to writing instruction, we diminish time for students to practice writing. Sometimes in the quest for structure or precision, we break down writing projects and guide students through them. Everyone writes an introduction on Monday. Everyone writes three topic sentences for the body paragraphs on Tuesday. Everyone writes the details of each body paragraph on Wednesday. This process can capture young writers to stay with the same writing project for two or more weeks and at the end they have only a few paragraphs.

When we allow students to develop fluency and stamina within a writing project, they finish the first draft sooner than when we lockstep them through. Granted, this first draft will not offer the precision or components drafts have when teachers lead students bit by bit in crafting a draft. However, I believe the benefits of allowing students to draft at their own pace—encouraging a fast and furious pace—far outweigh the precision and perfection of a lockstep writing project.

The point of writing workshop isn’t to produce a single project; it is to help each student become an effective and efficient writer. When we allow students the space to write their best first drafts, we provide opportunities to become stronger writers. Here's why.

Ownership Builds Confidence

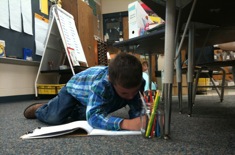

Writing is an art. Like all art forms, writing becomes most powerful when it is personal. By giving students space to fool around in the drafting process, writing less-than-perfect first drafts, we provide opportunities for them to develop ownership. They learn what works for them in getting words on the page. They figure out their best writing spots and their best writing tools. They learn whom they can sit beside and whom to avoid. As this ownership develops, confidence grows. The most important thing we can do for our students is to give them confidence in themselves as writers. When they believe in themselves, they become unstoppable.

Drafting Fluency Develops Over Time

Too many people are stymied by writing because they don’t know how to get words on the page. When students have the opportunity to craft their best first drafts, first facing the blank page and then making decisions about how to get going, they learn to develop fluency when writing. When teachers ask everyone to write a single paragraph or part of a project in one sitting, then young writers never learn how to keep going. As students face more experiences where they have to compose under a timed situation, it is important for them to develop a drafting fluency. It’s not enough to write a few sentences in a sitting; they must learn to draft fast and furious to become a fluent writer. Much like encouraging students to become fluent readers, we want to encourage them to become fluent writers.

Practice Makes Effective

We all know the old adage “practice makes perfect,” but we shouldn’t expect perfection from young writers. They are growing and developing. Rather than searching for perfection, a more worthy goal is to help every writer become more effective. To become better at anything, we must practice. Writing a single narrative or essay or persuasive letter is not enough to become more effective. Young writers need lots of practice writing. When Andy and I first got married, all of the side dishes for dinner were never done at the same time. The apple cobbler might come out first and be cold by dessert. Andy would watch the chicken so closely, the rolls would burn, and I’d forgotten to cook the peas. The rolls were burned so often that it’s still a joke between us: “Don’t forget the rolls!”

More than 15 years later, we are still cooking together. Today our timing is impeccable. It is the norm, rather than the exception, for everything to be ready on time. (And the biscuits are rarely burned.)

This happened because we practiced. The cooking didn’t get any easier. We cook bigger meals, with more side dishes, for our family of six than when we were newlyweds. Cooking is a hobby and has become more elaborate, but practice makes effective. This is true for anything in life—especially learning to write.

Next Drafts Aren't Always Revised Drafts

When young writers write a first draft (often much faster than I expect) and proudly announce, “I’m done!” I smile. I can’t help myself. I know the feeling of finishing something—even something that isn’t ready for publication. It feels good to write a whole draft. I give them a high five and celebrate with them.

I didn’t used to respond this way. Young writers popping up like movie theater popcorn and yelling, “I’m done!” did little to make me smile. I’ve realized that when students draft fast, there is plenty of room for revision.

Now I ask, “What are you going to write next?” Instead of helping them “fix” the draft they just finished, I encourage them to write something new—not a second draft of what they just finished, but a whole new writing project. If we are in a unit of personal narratives, I help them think of the next personal narrative to write. If they just finished writing a review of their favorite pizza joint, I ask if they have another restaurant they would like to review. Writing one of something isn’t enough practice; students need to write several drafts to learn how a genre works. Sometimes they need to write several drafts to find a topic that works.

When it comes time to revise, I invite students to select a draft that is worthy of their time and work to revise. I teach students to reread their drafts, looking for the one with the most potential. Then we are ready to revise in significant ways.

Messy Is Sometimes Good

Giving students space to draft at their own pace will never be as neat as guiding an entire class through a lockstep approach. It is messy. Some students write slim drafts, and others write never-ending drafts. There are missing parts and extra portions. However, it is through the mess that students develop the stamina and confidence needed to become capable writers.