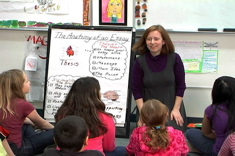

Teachers and coaches often ask us for a list of mentor texts to teach a particular strategy or genre unit of study. While we certainly have some favorites, we truly believe that when it comes to mentor texts we cannot lose sight of our purpose and audience. There are key factors teachers need to consider when selecting mentor texts: purpose, developmental stage of readers, and teaching objectives. Coaches have an additional factor — very limited time.

Our purpose in a demonstration lesson or a coaching session is to model something so that we can create a shared experience that inspires discussion, reflection and dialogue around instructional decisions and planning with teachers. We never have enough time for all we’d like to accomplish, so we look for short, potent texts that bring us to the teaching objective quickly. Here are a few texts that provoke deep thought, inspire accountable talk and allow us to complete the lesson in twenty minutes or less.

No, David! by David Shannon

This text is short, but there is so much you can do with it. We love it for modeling inferences, author’s message, character changes, conflict, connections, and fluency. As soon as you open to the title page and see the mom’s hands on her hips, you know what she is thinking, feeling and what she is about to do! We can hear how the mom is saying, “No David!” We can easily infer David’s motives and how his feelings change throughout the book. What type of person is David? Would you want to live with him? Why do you think David Shannon wrote this book? What is the author’s message to adults? Rich conversation begins almost instantly, and students can easily back up their opinions with evidence in the text since there is not much text to refer to.

When Sophie Gets Angry – Really, Really Angry by Molly Bang

Students begin to connect with Sophie before we even open the book. Who hasn’t been angry? We can already predict character motive, conflict, and theme based on the cover illustration. Students want to debate why Sophie is angry. Is it conflict between people or conflict within oneself? What is the theme? What is the author’s message? How does the author use color as a symbol in her illustrations? We can teach mood, conflict, and symbolism with this text. Since there is not a lot of text, it allows the students to really focus on the literary craft or strategy. When we can get kids thinking deeply right away, and we can model as coaches how to lift the quality of talk and thinking during a demonstration lesson.

Tough Boris by Mem Fox

We always used this book in kindergarten and first grade. One day we found ourselves unexpectedly in a fifth-grade classroom. We needed to cover this room for about 30 minutes. We had no plan, and the only text we had with us was Tough Boris. Like most elementary teachers, we are accustomed to pitching in and making do with what’s on hand, so we tried this text and were amazed where it took us. Is he really tough? What type of person is he? What is the theme of the book? What is Mem Fox trying to get us to think about in terms of stereotypes? What is the parrot a symbol for? What was the importance of the violin? What was the role of the boy in the story? How did Boris change throughout the story? What craft techniques did Mem Fox use to emphasize her theme? A sophisticated conversation ensued after reading this text we assumed was too basic for fifth grade. We now use this book all the time in grades 3-5 — we are amazed at the level of talk after reading only 70 words.

The Quiet Book by Deborah Underwood

We love this book for sensory images. You can get students hearing, feeling, seeing, and tasting by reading only one line. This book had many universal themes in it. Students can stick with one line and build off of each other’s thinking.

Some pages that have inspired the best talk for us have been:

- Last one to get picked up from school quiet

- Top of the roller coaster quiet

- Best friends don’t need to talk quiet

- Others telling secrets quiet

- Thinking of a good reason you were drawing on the wall quiet

What we have found is that kids not only relate to the sound, but to the feeling that situation produces in a person, and why we have that feeling. It is a powerful conversation about author’s craft when students discover the number of images Deborah Underwood can evoke with less than ten words. How did she do that? Why did she focus on a sound? Why is it so easy to have an emotional connection to the images she is using? Why are our images and connections different? She has also published The Loud Book!, and we are looking forward to using it as well.

The Dot by Peter Reynolds

This book inspires creative teaching in so many ways. It is great for modeling character and theme. This book gets kids thinking and talking about perspective — how is the message different if you read it from the teacher’s perspective versus the student’s perspective? Students quickly begin to ask:

Why did he write this book?

Why is the dedication important?

Is the dot a symbol? Why is the title not capitalized?

Why did the author use the font? How does the font add to the meaning of the story? How did Vashti change throughout the book and why?

We find that students can extrapolate the lessons in the book to many different examples in their own life.

One by Kathryn Otoshi

We are seeing this book used in so many schools to inspire conversations about bullying. We often use this book to model theme, inferring, prediction, character development, motive, author’s message, symbolism, and mood. We love that younger students get the basic message about the importance of being nice to everyone, and it is not okay to bully someone else. Older students get the more implicit message that if you are not part of the solution then you are part of the problem. They begin to explore the times when they have seen or heard something and have chosen to not get involved. They also love to explore how Otoshi uses colors and numbers, and how this adds to the meaning of the book.

Reflections

There are so many wonderful books to use to model our thinking and engage students in meaningful dialogue. Debbie Miller in Teaching with Intention reminds us then when thinking about mentor texts, “Authenticity matters. I can’t fake it. My connections, or questions, or inferences — whatever the strategy focus happens to be — must be genuine. That’s why book selection is key; choosing well-written picture books, narrative and informational nonfiction, and poetry that you love and can use over the course of a year to model a variety of strategies is essential. No matter how perfect someone else may tell you a book is, or how great a lesson they taught using it, it won’t be perfect unless you can connect with it and put your personal stamp on it in some way.”

As coaches we have the added pressure of time, and it is not always our best use of time to have teachers watch us read to students for long stretches. They want to see us model and facilitate accountable talk. The quicker the text gets us there, the more time we have to focus on this aspect of instruction during our demonstration lessons.