I have not had many struggles with spelling and conventions in my life. That being said, there are a couple of words I know are hard for me. Embarrass is one of them. With most words, if I have any question at all, I can write them, eyeball them, and accurately recognize whether they “look right.” With that one word, the e-word, my eyeball trick doesn’t work. If you lined up three different versions with varying numbers of r’s and s’s, I wouldn’t be able to tell you the right spelling without consulting my other strategy of remembering two sets of doubles. All I know from the choices is that spelling the e-word is tricky; I don’t know which one is the right choice.

I share this example because I see young writers having similar experiences on worksheets and even on teacher-created examples, especially when it comes to grammar and punctuation. “Find the mistakes” or “Circle the correct examples” are cues that there are some wrong examples in the mix. A set of multiple choice examples may show students three examples of incorrect work and one example of the work done right.

In a 2017 lecture at Teachers College in New York, Mary Ehrenworth outlined some important stages to consider as we teach grammar. First, students are able to recognize, then they can approximate, and then they reach mastery. She and her colleague Vicki Vinton have identified an additional stage they call “slippage,” which has to do with the number of times students are exposed to incorrect usages.

Mary reminded the audience of how often students see u as opposed to you, i as opposed to I, and more. Social media and texting contain a whole other set of rules and expectations for spelling and grammar, causing students to code-switch. Code-switching is when we alternate between two or more languages or varieties of language, such as how we talk to our children and then turn around and talk to our bosses. We all have to be aware of students’ ability to recognize and change their syntax and delivery, but also the confusion that code-switching may cause.

One of the points that has stayed with me since Ehrenworth’s lecture is the importance of showing students correct usages; giving the choice of a wrong way and a right way may not get the brain to remember the right way. The brain may choose instead to remember only that it’s complicated, especially if the brain is working on integrating and approximating other new information and skills at the same time. Therefore, whenever I meet with teachers about grammar and conventions, my recommendation is to give students as much exposure to correctness as possible when teaching complicated concepts or tricky situations. So what might that look like?

Shifting How We Ask Questions

| Instead of | Try this |

| Choose the correct word:

(They’re, their) going to (there, their) cousins’ house for dinner. |

Write in the correct they’re, there, or their:

__________ going to ___________ cousins’ house for dinner. |

| Which sentence is correctly punctuated?

“I love meatballs”, she said. “I love meatballs,” she said. |

Explain what makes the following sentence correctly punctuated.

“I love meatballs,” she said. |

The differences between the two examples are subtle, for sure. However, the right column does not present the choice of an incorrect response. Yes, students may create an incorrect response, but the hope is that by the time they are being asked to do this work, they know strategies to create the correct answer. As examples, they could look to their notes, ask someone, or use a system they’ve created for remembering. They can also use and study correct examples to create ones of their own.

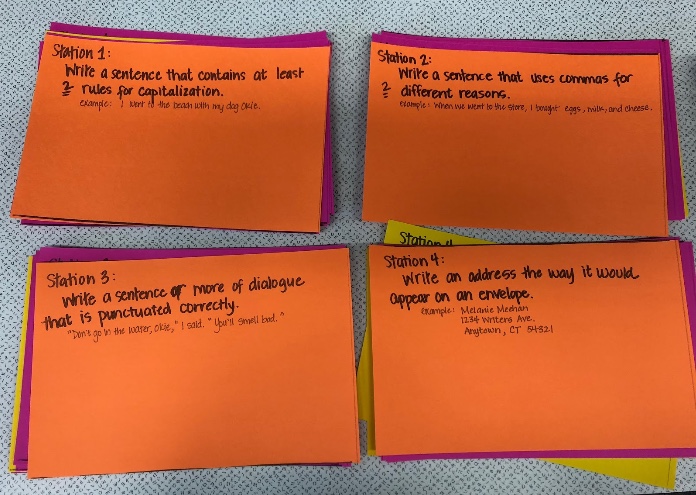

Setting Up Centers

Another way to build this “see it the right way” framework is to set up centers for writers. When I set up convention/spelling-oriented centers, I keep a couple of factors in mind:

- The activity should be short and able to be independently completed.

- The examples should be correct examples, as opposed to choices of correct and incorrect.

- Students should have to create or produce something as a result of the centers.

Remember that you don’t want to have students looking at incorrect examples and choosing between them, so try to keep it positive. Here are some possible stations you could create:

Write a sentence that contains examples of two rules of capitalization.

Example: We went to the park with Okie.

Rules: Capitalize the first word of a sentence and names.

Write a sentence or more that uses correctly punctuated dialogue.

Example: “Don’t go in the lake,” I said to Okie. “I don’t want your fur to smell bad.”

Rules: Comma is inside the quotation marks.

Period is inside the quotation marks.

Write a sentence that has two commas used for different reasons.

Example: When we go to the store, we have to remember eggs, milk, and butter.

Rules: A comma is used after a dependent clause and to separate items in a list.

Depending on the resources in the classroom and the skill level of the students, I may even make a chart that supports the center skill. For example, I may make a chart to accompany the second example about when we use commas. That way, when students work at the center, they have three experiences: they see a correct example, they review the rules about the skill, and they create something of their own.

I like centers for a lot of reasons. They offer flexibility in that we can change the number of them, their timing, and the skills. Additionally centers ask students to work independently, putting their knowledge and skills to use without an adult’s close direction. They can work with other students or on their own.

Brains are tricky. Sometimes we remember correct versions of information, sometimes we remember incorrect versions, and sometimes all we know is that we can’t remember! When it comes to students, the more we provide correct visual examples, the better our chances that they’ll retain and reproduce what we hope to see. In the meantime, I’ll keep working on my own e-word.