When we take a vacation to Disney World, our family has almost as much fun planning the trip as we do going on it. Once we decide how we’ll get there, we create menus of possibilities. We research various restaurants, read reviews of new attractions at the parks, talk about our individual hopes for the trip, and make a tentative plan for when we might do what. But once we get to Disney, our plans often change. A rainy day may require that we see a movie instead of visit the pool. A short line may be an opportunity to get an extra chance at a popular ride. We love to have plans, and it is always fabulous when they work out. But the planning phase is helpful even when things don’t go as planned. Planning always helps us know what the possibilities are when things don’t go as planned. Planning helps us enjoy our trip because of the options we have built in.

Planning a unit of study is much like that. I used to think of a unit of study as a set of daily minilesson plans. But I’ve realized that unit planning is not merely about creating lessons for several days. Several things go into planning, but I’ve come to think of unit planning as creating a menu of opportunities that can grow and change as we get into the unit. I’ve been teaching long enough to know I can count on certain things in my teaching. But I also know that every class is different, and if I truly go listen to my students, I can’t just follow the same lesson plans year after year.

So I plan a unit of study much like I plan a vacation. I dig in and study the big idea. I think of all the possibilities. I create opportunities, and I collect stacks of resources. I want to have as much available as possible throughout the unit, and I plan for flexibility. I find that when I know the big picture well, when I know where we are going and have at my fingertips a variety of things to support the learning, my students learn.

I follow the same steps when designing any writing unit of study. I determine goals, organize minilessons, collect resources, create scaffolds, and plan for sharing. These steps help me keep my eye on the big picture on a daily basis. Recently I planned a narrative writing unit of study, and this is the thinking I did.

Step 1: Determine Big Goals

The narrative unit of study is one of the first genre studies in our writing workshop. After we’ve developed routines and learned about living our lives as writers, we go into a unit of study on narrative writing. Of course a goal for that study is for students to learn to grow as writers of narrative text. But since it is our first unit of study, I have other, more important goals for the writers in my classroom—goals that will be important no matter what they write. Within the unit I want my students to begin to

- learn how to study a mentor text and use what they learn from other writers,

- use learning from minilessons in their independent writing,

- organize writing in a way that makes it easy to go back to,

- learn the power of revision,

- try new things while revising,

- use feedback to make their writing better, and

- find new ways to share published writing with others.

Step 2: Organize Writing and Minilesson Work

After students have become comfortable keeping a notebook, whether that is a traditional or digital notebook, I know that I’ll want them to have a place to collect writing and learning across a unit of study. I plan to give each child a folder with prongs to keep things from the whole-class minilessons—tools such as our district writing checklist, texts from minilessons, and their writing. For this unit, I brainstormed the minilesson topics specific to narrative that we’d be learning. I wasn’t sure of the order they would go in or how much time we’d spend on each, but I wanted them to have a visual reference as a reminder of the things to think about while writing narratives. So I created a sheet for their notebook with space for any personal notes as we went along.

Step 3: Collect a Menu of Books and Resources

I also know that I have to have a menu of books that invite playing with narrative as part of our minilesson work. I am always looking for new books to add to this menu, because I am never sure exactly which ones will meet the needs of this year’s writers. I try to collect them in a basket that I can use and then make accessible to students to revisit as writers.

Saturdays and Teacakes by Lester Laminack

The Relatives Came by Cynthia Rylant

Blackout by John Rocco

Blizzard by John Rocco

Marshfield Dreams by Ralph Fletcher

Knucklehead by Jon Scieszka

Fireflies by Julie Brinckloe

Step 4: Create Scaffolds for Writers

I’ve taken the advice of Kristine Mraz and Marjorie Martinelli and begun planning my boards and charts when doing my unit planning. In Smarter Charts, the authors share that “Kristine now plans the goals in her unit, any unit, first and then the charts needed to support these goals. Before starting any unit, she always asks, ‘What are the very big ideas I am teaching in this unit?’ . . . Once she has an idea of the three or four big goals, next is to start thinking about how each individual chart might go.”

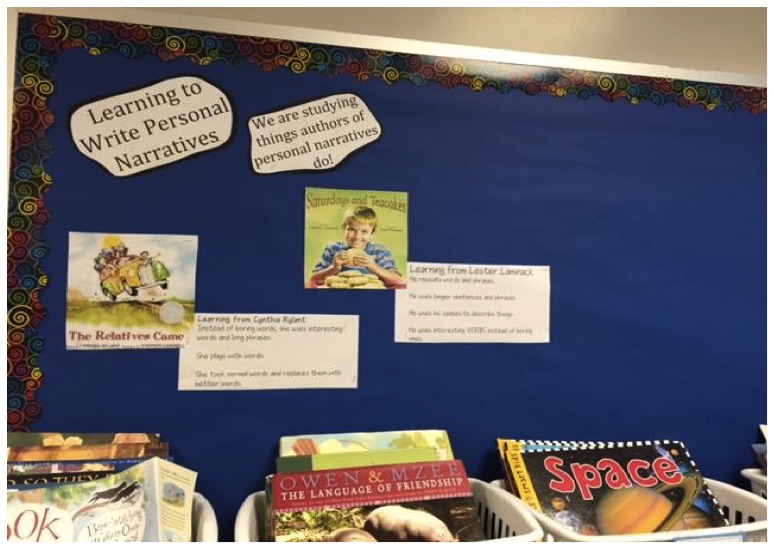

I followed their lead and planned out a board that would support writers as they became more skilled writers of narrative. I knew I wanted them to learn from mentors and I wanted those mentors to influence their own writing. I planned a board that would help us capture the learning from mentors and that writers could go back to during the writing process. We started learning from Lester Laminack, and the students created a chart listing the things we learned from him. We added those to the board and continued with other authors as we studied their work.

Learning from Lester Laminack

He repeats words and phrases.

He uses longer sentences and phrases.

He uses his senses to describe things.

He uses interesting verbs instead of boring ones.

Step 5: Plan for Sharing and Publication

Planning for daily share sessions for this unit was an important piece because I wanted students to think about ways to share their process rather than their products. I wanted them to understand that the share session was powerful in the way the community could help make their writing better.

I know third graders often think that sharing is about sharing writing with an audience, and we do some of that in the first few weeks of school to build community. But this unit gives us a good time to ask more of our writers during share time than to merely share writing. Planning for sharing meant brainstorming questions I might ask to move the share session away from product and toward process:

Does anyone have a new lead that they tried or a few leads they are deciding between that they want to share with the group?

Was there a word or a phrase in your writing that you were especially proud of today?

Having variety in the kinds of sentences you write helps keep the reader engaged. Does anyone want us to help revise a paragraph of sentences to make your writing more interesting?

How are you deciding whether you have enough dialogue? Does anyone want to share his or her thinking about where to include dialogue?

The unit of study was a success. The big-idea planning, rather than daily planning, helped me stay focused on what was most important so that students did not just go through the motions of writing.