I love nonfiction. I love learning about new things and broadening my horizons. But when I was a sixth grader, I was singing a different tune. I all but ignored the nonfiction books in our school and small-town library, and I couldn’t have cared less about social studies and science. Mostly, I sat through those classes in a daze, daydreaming about other things or counting paragraphs in my textbook during round-robin reading so I could silently practice the portion I would have to read when it was my turn. I know how dry, boring, and not-relatable nonfiction can be. But it certainly doesn’t have to be. Not only is there an amazing amount of vivid and engaging nonfiction available for kids, but there are ways to help kids connect and delve into nonfiction with purpose and relish.

My reader’s workshop has consistently been based on choice reading. The novels my students choose to read along with a read-aloud novel that I read to my classes are the basis of each minilesson. My classroom library, although stocked with hundreds of novels, picture books, and poetry, is somewhat limited in its array of nonfiction titles. The issue was how to incorporate a lot of nonfiction in a way that allows my students to not only enjoy it, but also share the experience and connect it to something they all may care about. The answer came to me as I was reading The One and Only Ivan by Katherine Applegate over the summer. I wanted to connect our read-aloud novels to nonfiction topics of interest.

As the first read aloud of the year, The One and Only Ivan made that goal easy to accomplish. My students and I not only fell in love with Applegate’s book and the characters, but were all inspired to know more about animals living in captivity. We focused on gorillas for obvious reasons, and I found articles, photographs, and video clips about these majestic creatures in the wild, their fight for survival, and reasons behind the capture and killing of gorillas. This led to even more articles and video clips on other forms of animal poaching—specifically elephants—and some stories of elephants held in cruel captivity. Before I knew it, we had read several articles, watched numerous video clips, and looked at myriad pictures to learn more about this topic. My students were increasing their schema for the topic, but also for reading and reflecting on nonfiction. They were talking—forming opinions, conversing, and writing academically about their thinking. They were posing arguments and backing them up with evidence compiled from all that we had been learning. They were owning the information and engaged.

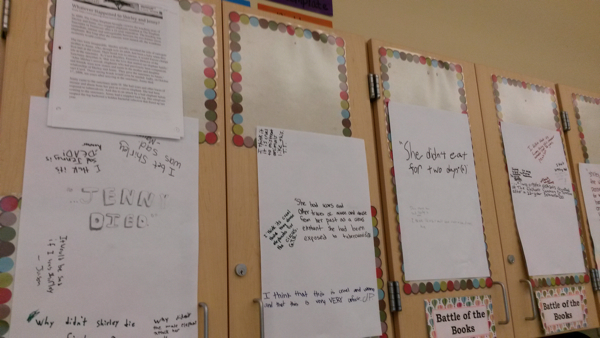

To keep the conversation going and mix things up a little, I tried something new. After watching a short video clip and reading an article about two former circus elephants who, after 25 years, were reunited at an elephant sanctuary in Tennessee, my students were to collaborate with their classmates and choose one quote from the article that they found to be thought-provoking or powerful in some way. They were to write this quote in the center of a large piece of construction paper (we were also learning to punctuate and cite quotes correctly). Then, each group member wrote their personal thinking about this quote on the paper around it. Each group then shared their quote and why they chose it with the rest of the class, and the pieces of construction paper went up on the wall.

To keep the conversation going and mix things up a little, I tried something new. After watching a short video clip and reading an article about two former circus elephants who, after 25 years, were reunited at an elephant sanctuary in Tennessee, my students were to collaborate with their classmates and choose one quote from the article that they found to be thought-provoking or powerful in some way. They were to write this quote in the center of a large piece of construction paper (we were also learning to punctuate and cite quotes correctly). Then, each group member wrote their personal thinking about this quote on the paper around it. Each group then shared their quote and why they chose it with the rest of the class, and the pieces of construction paper went up on the wall.

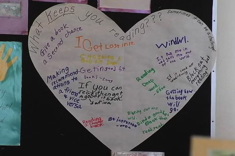

Later on during the week, we practiced adding more thinking to the pages. Armed with markers, students were asked to thoughtfully peruse the quotes and notice when something struck them. Each child then wrote a comment, question, or reflection of their own on the pages. Some of these additions were reactions or questions to the quote, and some were aimed at the thinking of their classmates and peers. Questions popped up, as well as answers to those questions. One of the benefits of making space for this (on a row of cupboards in my classroom) is that for all three of my language arts classes, students can have written dialogue across class sections and periods. The conversations can go further because more students are involved.

As the writing on the walls grew, I encouraged my students to review the new thinking and ideas that cropped up to see if they had anything more to add. In this way, the conversation continued to evolve. Responding to thoughts or quotes on the graffiti wall has become a nice option during reader’s workshop. In fact, it has spread a bit further. Students are commenting on the work in other areas of the classroom too. Anchor charts may have an added sticky note or two with a compliment, question, or reflection on it. I also can see that students are willing to talk more about the nonfiction we read, and they are readily making connections between various texts, both fiction and nonfiction, as their schema grows. All of a sudden, our learning, our thinking, and how it changes over time is a living and breathing visible component of our classroom.

As the writing on the walls grew, I encouraged my students to review the new thinking and ideas that cropped up to see if they had anything more to add. In this way, the conversation continued to evolve. Responding to thoughts or quotes on the graffiti wall has become a nice option during reader’s workshop. In fact, it has spread a bit further. Students are commenting on the work in other areas of the classroom too. Anchor charts may have an added sticky note or two with a compliment, question, or reflection on it. I also can see that students are willing to talk more about the nonfiction we read, and they are readily making connections between various texts, both fiction and nonfiction, as their schema grows. All of a sudden, our learning, our thinking, and how it changes over time is a living and breathing visible component of our classroom.