The launch of a new writing unit is an exciting time. Usually, students have just experienced some sort of writing celebration, and they have felt the pride and energy that comes with having an audience and a purpose. To keep up the energy and maximize instructional time, I have a few ideas as the new unit launches.

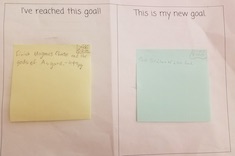

1. Pre-assess.

Pre-assessing means asking students to do what the unit is asking them to do at the end of the unit. Many teachers worry about standardizing the pre-assessment, making sure that they don’t do any teaching at all. I have a different take on this. If we are launching an opinion unit, I ask students to write the best opinion piece they can. I provide them with a chart of my expectations—the chart may vary depending on the grade level, but I go over the expectations I have before they begin writing. Then, as they write, I walk around and provide precise compliments, sometimes even with audible gasps. I say things like, "Wow, what a hook you’ve included in your beginning. Look at those transitional phrases. I’m impressed you remembered to use paragraphs. Your evidence is perfect for backing up your reasons . . ."

My rationale for providing this feedback is that if students can revise their writing just because they have heard me say some compliments to peers, then they probably don’t need much direct instruction on that skill. The purpose of the pre-assessment is to inform instruction.

2. Make the explicit connections between the previous unit and the current one.

Making the connections between personal narrative and realistic fiction is fairly obvious for many teachers, but these connections are not as obvious to students who don’t necessarily recognize that narrative writing is narrative writing. I was using the charts below around the room to remind students of their learning from the personal narrative unit. Their teacher had emphasized the concept of “Somebody wanted . . . but . . . so . . . and,” teaching into the concepts of problem and solution, character growth, and conflict and resolution, so that is what the initials stand for. The students approached their realistic fiction with great confidence when they realized from this chart that the only truly different element involved making up a character.

I have made similar charts with students as we have transitioned between information and opinion writing. Having the language of the previous and new genre on a chart in front of students really helps them transfer previously learned skills.

3. Ask students to share what they already know.

Students love to be experts on topics, and when we ask them what they already know, they surprise not only us, but also themselves. Sometimes we don’t know what we don’t know, but sometimes, we don’t know what we DO know. All of the writing genres repeat throughout the grades, although the expectations grow. A sixth-grade teacher facilitated the creation of the charts below, but this process could happen in lower grades as well. Because she teaches three separate sections, her students used different colors for different classes. They had to read what was already on the charts before adding to them. As she worked through her teaching points during the unit, the classroom teacher could refer the students to the charts that they created.

Sometimes we use precious instructional minutes teaching what students may already know and be able to do. Using any one or a combination of these three strategies may help maximize the time teachers have to create meaningful learning experiences.