“I suggest the crime was committed in the lounge by Mr. Green with the wrench.”

Can you prove the suggestion false? Ah-ha, you happen to have a Clue card representing the lounge so your evidence proves that there was no crime committed in the lounge, not today my friend.

Evidence is essential for making accurate accusations in the game of Clue, and will be increasingly important as we transition to the Common Core Standards.

The very first Common Core Anchor Standard in reading states:

Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

We pull out the main verbs of this standard — read and cite. What are we reading? The text — closely — for the purpose of making logical inferences. What are we citing? Specific evidence for the purpose of supporting conclusions.

Shifts Around Reading Closely

In the description of the game above, the player was able to cross the lounge off of the check sheet. They made a conclusion, based on close attention to the “clue.”

Reading closely requires students to slow down and consider the intention of the author. This brand of “scholarly reading” pushes readers to make careful meaning from texts, grappling with the message intended by the author, rather than piecing clues together with snippets of “This is kind of like . . .” and “I’ve heard something like this before and . . .”

The role of the teacher is that of masterful detective. Careful prereading of text allows the teacher to sleuth out exactly where to stop and draw attention to the language of the text. She or he works to craft questions intended to pull students into the text and activate thinking. This time spent planning reflects the ultimate goal of the shift: rigorous thinking about the meaning of the text.

Detective work takes time. Often, the game of Clue goes on for hours, as the players work to piece together all that they have inferred from their cards. This shift also requires time. Prereading with the intention of formulating engaging, text-based questions doesn’t come easily. As literacy coaches, we see ourselves supporting teachers in acquiring competence with this skill. As teachers, time will be spent supporting students in developing their thinking while keeping it grounded in texts. The result will be deeper comprehension, and the ability to defend ideas and opinions in a way that is both thoughtful and precise.

Shifts Around Citing Specific Evidence

If we want our students to support their conclusions with evidence we need to start with where they are at, be it kindergarten, fourth grade or ready to graduate from college. Let’s look at informational and literary examples to put this in context for our students.

Underwater Life by Patricia Miller Schroeder begins with these words:

All living things have a life cycle. They begin life, grow, reproduce, and die. Some underwater animals, including frogs, change shape as they grow. This type of change is called metamorphosis. Not all underwater animals go through metamorphosis. For example, amphibians such as frogs change shape, but mammals do not. A whale is a mammal . . .

If a third grader then is to “ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers,” we might ask, “After reading this informational text on life cycles, does a whale start out as an egg and go through metamorphosis? Share evidence from the text to explain how you know.”

Here are some written responses we might see:

No it doesn’t, that’s silly.

No, because I saw a National Geographic Special.

If we are looking for a response using evidence from the text, it might look something like this:

The text said a whale is a mammal and that mammals don’t change shape and go through metamorphosis so my answer is no.

Notice that the question didn’t simply ask the kids to respond at the literal level, but asked them to use two separate pieces from the text — “a whale is a mammal” and “mammals do not (go through metamorphosis).” The clues are there in the text, but the detective reader has to put them together for a conclusion.

In Thank You, Mr. Falker, by Patricia Polacco there is a precious exchange between a teacher and student:

But Mr. Falker caught her arm and sank to his knees in front of her. “You poor baby,” he said. “You think you’re dumb, don’t you? How awful for you to be so lonely and afraid.”

She sobbed.

“But, little one, don’t you understand, you don’t see letters or numbers the way other people do. And you’ve gotten through school all this time, and fooled many, many good teachers!” He smiled at her. “That took cunning, and smartness, and such, such bravery!”

Then he stood up and finished washing the board. “We’re going to change all that, girl. You’re going to read — I promise you that.”

Those same third graders are expected to “ask and answer questions to demonstrate understanding of a text, referring explicitly to the text as the basis for the answers.” We might ask, “After reading about Mr. Falker and Trisha, is he angry at her for fooling her teachers? Share evidence from the text to explain how you know.”

Here are some written responses we might see:

No, he’s not mad. That would be mean just because she couldn’t read.

No, no one should be mad at her.

If we are looking for a response using evidence from the text, it might look something like this:

The text says that he smiled at her and gave her compliments like being brave. Then he promised her she would learn to read so he wasn’t angry at her.

What’s Next?

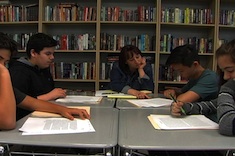

Reading closely looks like kids looking back at text, rereading, pointing to lines, and underlining as they make meaning. It sounds like readers asking themselves, “Where was that line?” and “I remember the text said…”

Citing specifically looks like kids copying phrases and sentences from the text, synthesizing evidence from different locations of the text, and drawing a conclusion. It sounds like writers asking themselves, “Where did the text tell me that?” and “How do I use evidence to explain?”

With each of these shifts we begin with a student-centered approach: What will students need to know and be able to do? And then work backward to think about what, in turn, teachers will need to know and be able to do. This shift implies that teachers know how to ask questions that take kids back to the text, and know the difference between literal (exact words contained in the story), inferential (putting two or more ideas from the text together) and critical questions (questions answered from the author’s point of view via the text). It also implies that teachers are helping students make connections to reading through speaking and writing. We know students are likely to start by answering questions with no evidence, or answering questions with opinions and experiences. What support will they need as they become detectives, making stronger connections between their ideas and texts?

As we work through these shifts and standards, it’s with some discomfort. Talking together, we keep a healthy wariness about shifting too far with this standard. Yes, kids will be better citizens if they use evidence for their conclusions. Yes, we want readers supporting their conclusions in writing. Yet we don’t want to lose sight of the importance of connections kids make when they answer questions that take them at times away from the page, and back again.