A high school teacher tells me, “The students aren’t coming from the middle school with the grammar skills we expect of them.”

The middle school teachers ask me, “Are elementary teachers even teaching grammar at all anymore?”

A team of elementary teachers admit to me that they’ve hung on to outdated grammar reproducibles, “We don’t know what else to do besides drill it into them.”

The worry about not preparing writers is understandable. Problems with grammar and mechanics can become an obstacle for students trying to get their message across. But are outdated grammar reproducibles really the way? As a teacher I never saw those fill-in-the-blank skills transfer to students’ writing. The Carnegie Foundation reviewed the research in their Writing Next report and found:

Grammar instruction in the studies reviewed involved the explicit and systematic teaching of the parts of speech and structure of sentences. The meta-analysis found an effect for this type of instruction for students across the full range of ability, but surprisingly, this effect was negative. This negative effect was small, but it was statistically significant, indicating that traditional grammar instruction is unlikely to help improve the quality of students’ writing.

A teacher said to me, “Kids just need explicit teaching of grammar. They don’t even know the difference between verbs and nouns anymore. And the students who struggle to write need it even more.” Yet the research again is conclusive: struggling, low-achieving students had negative results with isolated teaching of grammar skills.

Drill and kill is not the way to build writing skills.

Put It Together

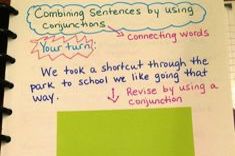

What did rise up out of the research with positive results is sentence combining. William Strong in his book Writer’s Toolbox: A Sentence Combining Workshop explains, “As its name implies sentence combining involves putting sentences together, using what you already know about language from your own experience of speaking and reading. The sentence combining approach mirrors what happens when you put meanings together in everyday life.”

Many traditional grammar practices involve taking sentences apart. We ask students to insert the missing punctuation or identify the subject. In Daily Oral Language we give them something incorrect to dissect and correct. Diagramming sentences is an obvious pull-apart strategy. In contrast, sentence combining is a putting-together approach. William Strong uses clusters of sentences and a problem-solving approach to writing.

For example,

I like my mom.

I like my dad.

I like my whole family.

These were a first grader’s three sentences when I sat down to confer with him. Although listy, these sentences are complete and correct as they are. I invited the young writer to play with the sentences after I gave him two examples.

Possible sentences:

1. I like my mom and dad. I like my whole family.

2. I like my whole family, especially my mom and dad.

I asked, “Which one do you like most?”

He said, “I like the second one.”

“Why?”

“Because it sounds good.”

“Okay,” I said. “What did I do to make it sound good?”

We studied the sentence and noticed that I used the word “and” to put his mom and dad together and “especially” to make his mom and dad sound special. Grammatically, I turned his simple sentence into a complex sentence. That is, the first sentences all had one independent clause per simple sentence and we changed it to “I like my whole family, especially my mom and dad,” which has an independent “I like my whole family” and dependent “especially my mom and dad” clause, forming a complex sentence.

If you need review on distinguishing between simple, compound, and complex sentences, this short video was helpful to me.

Using the analogy of Legos (which the young first grader loves), I encouraged him to go back and try building sentences with more parts to them. Instead of writing strings of simple sentences, he was hard at work building complex ones.

Older Writers Also Benefit from Sentence Combining

Consider this cluster of sentences:

The government was shut down for 16 days.

The cost of the shutdown was $2 billion dollars of lost productivity.

This also affected people who weren’t furloughed.

There are many possible ways to combine those sentences:

1. Because the government was shut down for 16 days, it cost $2 billion of lost productivity and even affected people who weren’t furloughed.

2. Two billion dollars of lost productivity was the cost of the 16-day shutdown that affected everyone — even those who weren’t furloughed.

3. Even if you weren’t furloughed, you were probably affected by the 16-day, $2 billion dollar government shutdown.

Read these aloud. Which one did you like best? Try writing one of your own. Now imagine middle schoolers, high schoolers, and even adults taking clusters of their own ideas and playing with them. By engaging in decision-making, writers use what they already know about language and build on it.

As William Strong writes, “This process of fishing — pulling in possible sentences and then making choices — lies at the heart of sentence combining. No one can tell you how to do it. It’s something you have to experience.”