Helping children learn to listen to each other well and give feedback takes a great deal of time. For many years, I just assumed that kids intuitively knew how to talk to each other. I could just write on a to-do list, “When you feel like you need a conference, ask a friend” and everything would work out just fine.

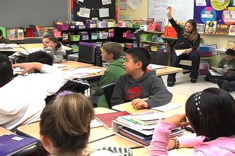

The writing workshop in my fourth-grade room looked fine. Kids were writing, sharing, and revising, and they seemed to be enjoying themselves. It wasn’t until I actually took the time to listen in on some peer conferences that I realized I hadn’t set them up for success. For about a week I listened to conference after conference after conference that had two parts. Child A would read his or her entire piece aloud to Child B. Then Child B would say, “That was great! Do you want to hear my story now?” Students would swap roles, and after 10-15 minutes, both walked away feeling good, but without any specific feedback or tips to help make the writing stronger.

This week of observational inquiry happened a few years ago, and since then, I have worked hard to take the time to establish norms that will help the writers in our class use the time of peer conferences more effectively. We spend a great deal of time the first six weeks of school just learning how to listen and respond to each other in a variety of situations. Then we start layering in norms for writing conferences. Being explicit about how we should talk with each other instead of at each other is hard work. But if you take the time to establish and practice some norms, the way students converse will become routine.

Invitations

Invitations are enjoyable to receive, unless you are being invited to a party celebrating an intolerable family member or work colleague. When we get an invitation, we feel included and usually figure out a way to honor it. However, when we are directed or commanded to do something, we often feel resentful. Think about being invited to a book talk before school with colleagues versus the mandatory staff meeting called last week that wasn’t on the schedule. Chances are you are more positive about the former.

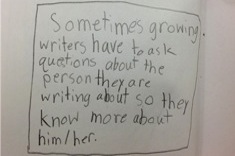

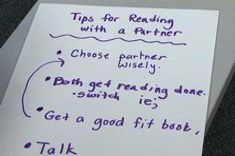

If we can help our students give feedback that sounds invitational, then the author’s stance changes. When we are helping students develop ways to give critical feedback, we are helping them invite a fellow author to see his or her writing through different eyes. We model this type of talk in whole-group as well as one-on-one conversations. The class discusses how we can phrase feedback. We draft anchor charts that give some possibilities for how to phrase constructive feedback. And maybe most important, we walk the talk. We use the language that has been set up as exemplars. We take the time to check in on peer conferences as outside observers. We listen carefully to our students during their peer conferences and provide subtle feedback when needed.

Our goal is that instead of hearing phrases like, “You need to fix your spelling mistakes” or “You need to add more detail,” a shift will happen and we’ll start to hear things like, “You always have good details when you describe a character. Have you thought about doing that when you describe the setting?”

Here is a video example of how I work with my class to teach the principles of thoughtful, invitational response:

Setting goals for ourselves as writers is crucial. If you are like us, you need to have the accountability of setting a goal to get your butt in a chair and write. Children need to be able to set goals as well. The children we work with tend to set generic goals like “I will publish a novel with several sequels this year” or “I want to be a better writer.”

One of our current questions is how setting a goal based on the feedback from a peer conference would affect our writing. For example, if during a peer conference, Jackson hears, “The beginning of your story really pulled me in, but toward the middle I got a little confused with all the talking between the characters,” would he be able to frame a goal that might not only help him work on the confusing part of the story, but help him in the long run as a writer?

In this second video example, I coach two boys working through how to balance compliments with critiques:

Helping children frame goals that will propel them to become better writers is difficult work. To be honest, my students still often set overly general or lofty goals. But I have seen some small successes. We want our students to be independent goal setters. I think that if during the time they spend in our writing communities our students can become better at setting goals independently, they will become writers for themselves, not just writers for school.