“Wait a minute. Is there a turtle in this book or not? Are you saying that the turtle shell is a way to describe the preacher’s feelings? I completely missed that. Can we talk more about what the turtle shell means?”

This was one student’s comment during a grand conversation about Because of Winn Dixie. Her thoughts reveal her confusion, and we can almost see her brain constructing more profound ideas right there in the meeting area.

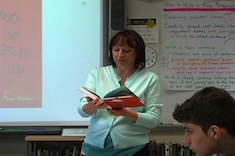

Whole-class grand conversations happen about once a week during read aloud. When the class gets to a compelling part of the text, finishes a book, or shares some exciting interpretations, our next read-aloud session becomes a time for talk. Making time for whole-class conversations is a conscious decision. I want students to know that their ideas matter, so I devote 15-20 minutes a week to student-led discussions, so students can share their interpretations, listen to others, and develop more sophisticated theories.

A few key tools will help students when they are new to grand conversations:

- The Whole-Class Notebook

This is an enlarged notebook that one partnership a day writes in during read aloud. These notes help the class prepare for our grand conversations and teach them how to record new ideas after the conversation has ended.

- Anchor Chart of Accountable Talk Sentence Starters

A chart with helpful, accountable talk language grows as the weeks pass and student talk becomes more sophisticated.

I heard you say . . .

At first, I thought . . . but now I think . . .

This makes me think . . .

In the text it said . . .

So maybe . . .

I would like to add to [student name]’s idea.

I see it differently from [student name].

With these tools accessible at the rug, the grand conversation begins. I keep the process for grand conversations clear and focused because I want students to internalize the steps, so they can use a similar process when they meet with their reading partner or book club. These steps become much shorter as the class becomes more comfortable with grand conversations.

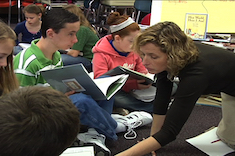

Step 1: Students sit in one large circle, next to their turn-and-talk partner or with their book club so that everybody can see each other. It is crucial that when we talk, everyone has a “front row” seat.

Step 2: Together as a class, we review the notes in the whole-class notebook and think together about possible talk-worthy ideas. “We have so many ideas about [title of the text]. Which ideas do we think are talk-worthy? What do we want to talk about as a whole class? Turn and talk.”

As I listen, it is often easy to connect kids’ ideas to curricular goals and the current unit of study. If students don’t mention a particular idea, I ask them to think with their partner about a more in-depth idea. I might prompt them to think about how characters affect each other, possible literary themes, or even the author’s craft moves they noticed.

Step 3: Next, the group chooses one question or idea to discuss. Sometimes, the majority of the class wants to talk about an idea and we go with that, whereas other times, I focus on a particular literary element or device that connects to our learning goals. Either way, choosing one idea helps the class learn how to elaborate on a topic and build ideas off of each other, rather than moving from one topic to the next.

Step 4: Then, the conversation begins. During this grand conversation, there are a few essential ground rules:

- We do not raise hands, but we do look at the person who is speaking, and the speaker tries to look at all of the students instead of at the teacher.

- Students use each other’s names as they speak. For example, if they want to build on someone’s idea, they might say, “[Student name], I heard you say [X], and I would like to add to that.”

- We try to include everyone and not monopolize the conversation. Some students have difficulty holding back, and others stay quiet. As time goes on, we encourage students to notice both of these behaviors in themselves. We say that if you have difficulty holding back, one way to help is to ask a student who hasn’t had a turn to speak, “[Student name], what are you thinking?”

- Students refer to the whole-class notebook when necessary. They turn the pages to find specific evidence to support their thinking.

Sometimes these conversations go well, and at other times they stall. The students are learning the art of conversation, and that takes time and practice. The groups sit through the long moments of silence, and I let them work it out when two or three people talk simultaneously. It is all important learning. As the weeks go by, conversation skills grow.

Step 5: At the end of the conversation, I ask, “So what is our new thinking? How did our ideas grow based on our conversation?” One partnership records the new idea in the whole-class notebook, and we end for the day. I want kids to know that conversations change us, and our thinking gets altered when we converse with others.

Step 6: The next day, we reread this new idea or question so students can ponder it as we continue reading the text. Then we delve right back into our read aloud. In five days or so, the class will launch into another grand conversation.

It isn’t hard to dedicate time to this practice when we see how many learning opportunities are embedded in grand conversations. During these weekly talks, kids practice how to listen and connect their ideas, how to state their points clearly, how to ask questions when they don’t understand, and how to take turns when multiple people are part of a conversation. As the students talk, they learn ways to share ideas and respond to others.

Grand conversations also deepen students’ comprehension. As students talk, we learn which parts of the plot were confusing, when they’re struggling to keep track of the characters, and the types of ideas they think about as they listen to the read aloud. I would never have known that the student was confused about the turtle shell reference if she hadn’t had time to talk. It is incredible how much teachers learn when we step back, watch, and listen.