The district in which Kate coaches has teachers in grades 1-5 who are comfortable with guided reading. Three years into reading workshop, many are ready to try strategy lessons as part of their reading workshop instruction but feel unsure about how to begin.

To support teachers in making the transition to incorporating more strategy lessons, we focused on some explicit teaching about the differences between guided reading and strategy lessons, modeling what strategy lessons look like and supporting teachers in mining student data to inform the focus for strategy lessons.

Considering Purpose

Guided reading is one structure that upper-elementary students might need at specific times. When a benchmark reading assessment reveals that a student isn’t progressing through levels independently, for example, guided reading for a short period of time could help that student make the transition from one level to the next.

But overall, as the focus in reading for middle- and upper-elementary readers shifts from decoding to comprehension, we find that large chunks of reading independently is what most students need if they’re going to grow to love reading. That means shifting our focus from guided reading to conferring and strategy lessons, which are grounded in students’ just-right books.

Guided Reading Versus Small-Group Strategy Lessons

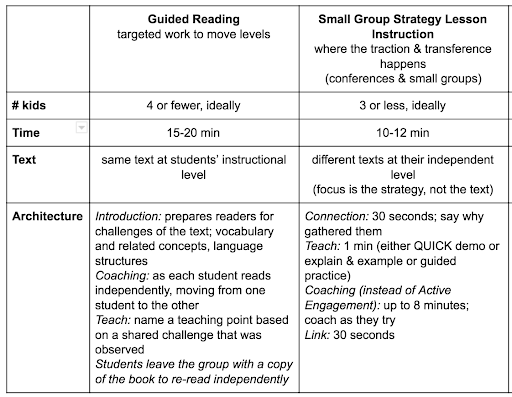

To help teachers understand the differences between guided reading and strategy lesson groups, we shared the chart below so they could see them side by side.

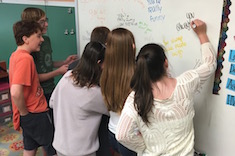

Modeling Strategy Lessons

We decided to focus our work with teachers during our reading workshop cycle on conferring and small groups, which created opportunities to model strategy lessons for every teacher who expressed interest in and readiness to try them. We handed the observing teachers a copy of the chart above so that we could refer to the parts of the strategy lesson as we modeled it. Many teachers liked comparing the structure of a strategy lesson with that of a minilesson, which they were already comfortable and familiar with, having taught reading workshop for three years. We’d show how the structure is the same, with a main difference being that the teaching in a strategy lesson is abbreviated so that the coaching/active engagement can be longer.

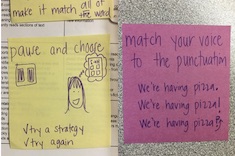

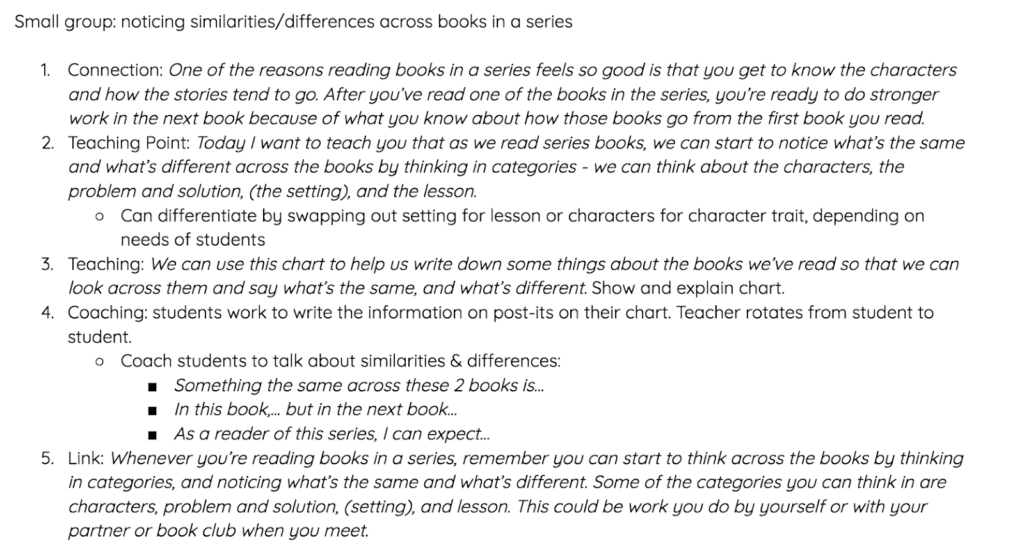

When the strategy lesson was discussed with teachers in advance rather than being something we decided on the spot, we’d come with a typed plan that we could leave with the teachers to support them in replicating the group themselves. The one below was modeled in a third-grade classroom involved in a series book club unit:

Copycatting strategy lessons in this way—trying the same strategy lesson we modeled with a new group of students—seemed like an entry point most teachers were comfortable with.

Determining the Focus for Strategy Lessons

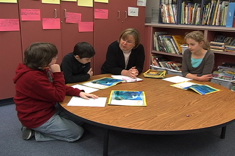

To support teachers in determining the focus for the strategy lessons, we provided them with time (during their PLC meetings, staff meetings, and PD days) to look at the reading data they were collecting.

We began by brainstorming a list of different lenses through which teachers could look at student data, using what they were already doing as reading teachers:

- Assessments: iReady, Rigby

- Engagement: volume/stamina—comes from kid watching and/or reading logs

- Guided reading data—fluency, vocabulary, specific reading skills, anecdotal notes

- Turn and talk: follow-up on ML

- Read aloud data

- Conference notes

- Jot Lot sticky notes

To simplify the process in the beginning, we chose which data teachers brought to the meetings. We focused on anecdotal notes from reading workshop conferences and guided reading along with their running records from the Rigby assessment.

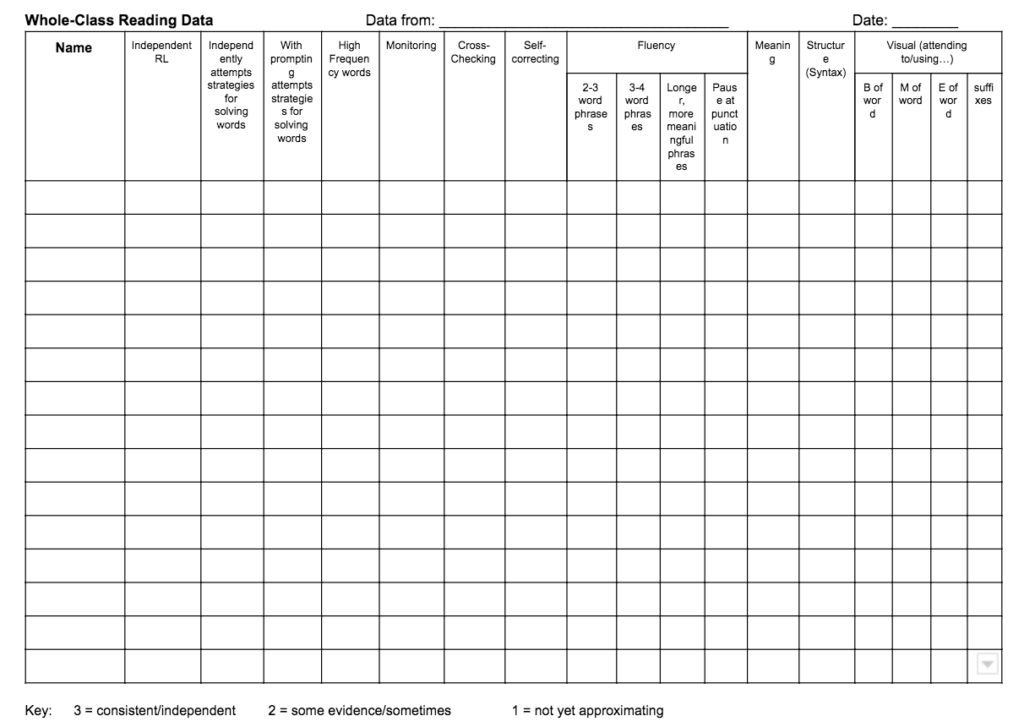

We also gave teachers a tool for organizing their data. Because most of their teaching in conferences and guided reading focuses on decoding and fluency strategies, we created the chart below for first-grade teachers. Teachers looked across students one at a time and filled in the columns to give a picture of each reader as a whole, across the different data types.

Once the class was recorded, teachers looked down columns to find similarities across groups of students and created groupings for strategy lessons. In addition to being there to support analyzing the data and moving it to the whole-class chart, we helped teachers brainstorm different strategies and teaching points that could be taught in the strategy lesson groups to address the needs they were seeing.

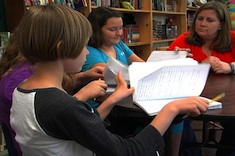

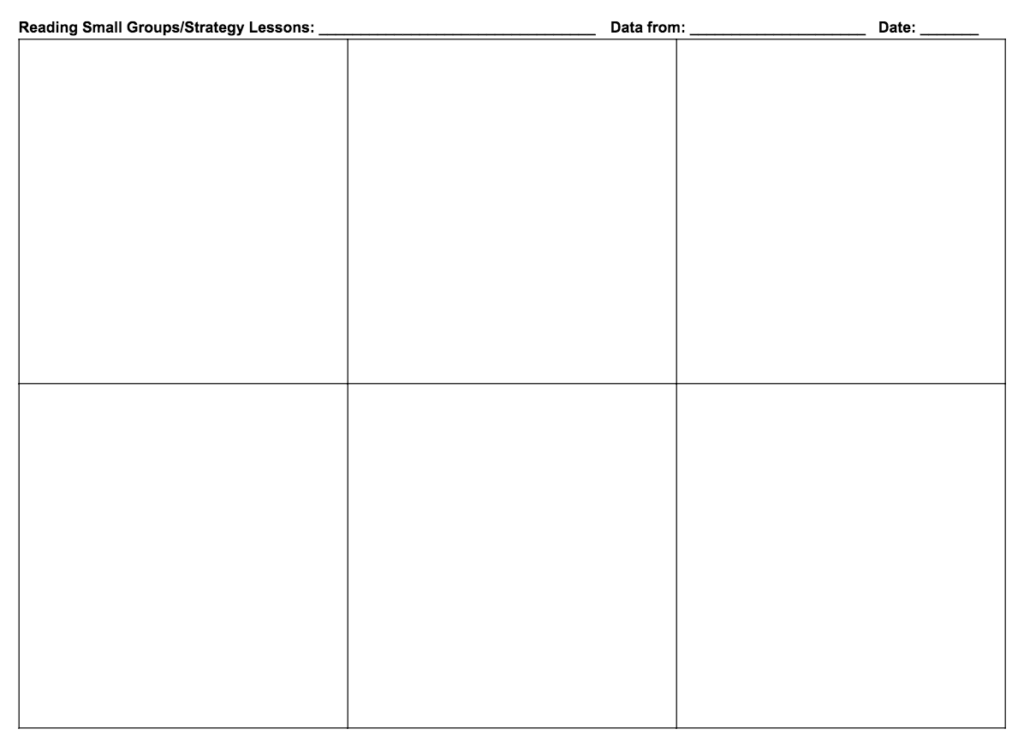

We gave second- and third-grade teachers the simple sheet below with some sticky notes. As teachers flipped through their data, they’d write a possible focus for a strategy lesson group at the top of a sticky note and put a student’s name underneath it. As they looked across more students, they were able to add names to strategy lesson sticky notes they had already made or create new notes.

We emphasized that having six strategy groups would carry the teacher for many weeks of strategy lessons because each group would likely lead to additional groups. Some students would need reteaching, or the work they did during the strategy lesson would give the teacher ideas about other next steps.

Providing the teachers with time to analyze their data helped reinforce the reason they were collecting it in the first place. We also provided support to any teachers who needed it as they began using the data to inform their instruction. Giving them the time to do it also helped lessen the feeling that it was one more thing they were expected to find time for in their already busy days. All teachers walked away from the meetings with plans for strategy lessons that were responsive to the needs of their students.

By providing teachers with some explicit teaching examples around the purpose of, and differences between, guided reading and strategy lessons; modeling strategy lessons in their classrooms; and giving time and support to analyze their students data and plan strategy lessons, we gradually released responsibility of the strategy lessons to teachers.