The topic of grouping for literacy, especially any grouping that involves sorting children according to their abilities, is charged politically and can polarize teaching communities. The key in my classroom is to be flexible, basing groups upon the specific skills that will be developed in the group. There are no set groups in my classroom; students have freedom to move in and out of small groups based upon their changing needs, the group focus, and students’ growing awareness of those needs.

I think about when and how to group daily. The school day is rich with opportunities to learn about words – vocabulary, decoding and spelling strategies, and features. These grouping opportunities are both planned and spontaneous.

Assessing Before Grouping

I do not put any students into small groups until I have built relationships and trust with my class. I need to get to know them as learners first, and we need to have a solid community in place. At the beginning of the year, I mix whole-class instruction with individual conferences, and gather lots of information about each child and the class social dynamic before I begin grouping.

I appraise my students’ writing daily, looking for word learning confusion (spelling and vocabulary) and listen to my students read, noting miscues. I then ask myself, “Which students have similar confusion, and what are the roots of the confusion?” This question helps me determine a focus for small-group word work. Then I consider at what point in the school day I should bring these students together for focused word learning.

Group Formats and Duration

My small-group lessons are short (usually no more than ten minutes) and focused on immediate needs, because I want my students to practice these skills in real contexts. My goal is independence and automaticity with the word learning feature. These groups are temporary, lasting no more than a couple weeks, based on students’ emerging understandings of word study concepts as they apply to the reading/writing process.

When I pull students over for small-group instruction, texts are a key consideration. I need to be careful that my word work instruction is not asking students to practice skills and strategies in isolated texts, divorced from the reading of their classmates. I try to use the same text the remainder of the class is reading (i.e., textbook or whole-class read-aloud chapter book) or something popular with students for independent reading (i.e., a news magazine like Time for Kids

Understanding the Social Nature of Academic Groups

I always consider the social dynamics of pulling together small groups. First, bringing together a group can send the message that this group is not smart. I know the first time I pulled a group for word work with last year’s class I was anxious. One of the participants in this group was a class leader and soccer queen, Amanda. I briefly chatted with Amanda about my desire to pull her over and work with her with a group of peers she normally did not interact with. Amanda’s reply was matter-of-fact with no stigma attached, “I stink at spelling, thanks.” Amanda relieved me of my worries, and I felt more comfortable flexibly grouping kids based on specific short-term goals. I realized by that point in the year (late in the fall), I had created an environment where students like Amanda were secure in their strengths as learners, and so felt comfortable working in groups to develop new skills in other areas.

I have also found that it’s always useful to issue an open invitation to the remainder of the class when beginning a new group, asking anyone if they would like to join. This reinforces the notion that we are targeting short-term specific skills and needs in each group — not labeling classmates broadly as more or less able than their peers academically. In my class, all students are responsible for monitoring their reading and writing process through notebooks, logs, class discussions, and conferences with me. I am always pushing them to think about what they can do well, and what they might work on next — to take responsibility for their learning. Because students are always analyzing their literacy development, they know instantly if a group topic or skill is something they might need and they are free to join in.

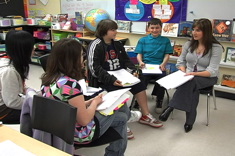

The added benefit to these flexible groups has been the discussions within the groups. I’m fascinated by how students with a range of abilities scaffold each other. Students that normally would not interact socially are discussing their thinking and strategies as they work towards a common learning goal.

Grouping to Teach Spelling and Convention Strategies

The most effective small-group lessons for my students are the ones that focus on spelling features. Students have such different needs as spellers, and there are myriad strategies I can pick for a group. They also know many adults who are very bright and still struggle with spelling, so no one loses face by acknowledging problems with spelling.

The duration of these groups vary, but they average about two weeks. The small group meets with me for roughly five to seven minutes each day, working with a spelling feature or convention strategy that supports their learning to look at print in new ways. I use the groups to support their understanding of the generative nature of spelling, and help them connect known spelling patterns to unfamiliar words. A sample lesson I might use in one of these small groups can be found by clicking here. This particular group was focused on learning to capitalize proper nouns.

Amanda’s comment in blithely accepting her need for some group instruction and my relief afterward remain with me as I start the process of observing and planning for small groups with this year’s students. I will again take on the challenge of flexible grouping — but only after my students and I know each other well.