Revision can be a difficult process for many writers—kids and adults alike! As writers, we both know how difficult it is to come up with a topic, get our ideas down on paper, think about how to communicate what we are really trying to say, and then revise the piece to make it clear and engaging. Professionally, we tend to write in tandem. We typically begin by talking through an idea and generating thoughts. Then one of us takes a crack at the first draft. The other person reads it and gives suggestions for revisions. The revisions can go back and forth several times between us before the draft is complete.

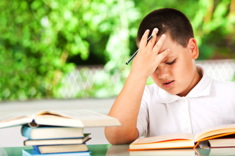

When we think about the writers we encounter who struggle with encoding, handwriting, processing, and organization, we cannot help but think about how difficult the process of revision must be for them. Unlike struggling students, we do not have to think about how to get words on the page, yet the process of writing and revising is still hard for us. How must it feel for our students who have difficulty with even the most basic elements of writing?

Struggling writers have wonderful stories to tell, yet they often see themselves as poor writers. They cannot find a way to get their ideas down on paper in a manner that makes sense. They cannot demonstrate what they know to their readers. They end many workshops feeling frustrated and defeated by the writing process. We have been thinking about them a lot, and have discovered some techniques that help students who struggle get their ideas down on paper and revise their writing.

Strategy 1: Talk It Out First

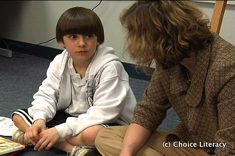

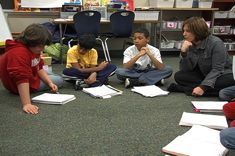

When we give students time to talk through their piece several times before they actually begin writing, they have an easier time getting their thoughts on paper in an organized fashion. The verbal rehearsal of ideas allows them to solidify what they want to say and clarify the sequence of their pieces. We find that most of these students will even begin revising during this verbal process. Typically, students begin by telling their story to a partner; they then confer with a teacher and tell the story again, and finally, they tell the story to another partner. Once students sit down to write, they know their stories well, so they can focus more on getting their ideas on paper. Releasing them from spending excessive effort thinking about the content gives them the capacity to focus on processing and encoding.

The other benefit to the verbal rehearsal is that now several people know the writer’s intent for his story. If the writer has difficulty remembering what comes next in his story or is getting off track, his partners can remind him what he planned and question why he is changing the story. This helps the writer stay on track and bring clarity to his writing.

Strategy 2: Keywords on Sticky Notes

We have met many writers who know what they want to say but are a few pages further ahead in their mind than they are on paper. We have found that showing students how to use sticky notes to capture keywords for the next four to five events in their story helps them write their story step by step. At first, we model this with students in a conference. Over time, they begin to use the strategy independently. Writers begin the workshop by looking at the previous day’s sticky note, rereading what they wrote, and then planning the next four to five events on a new sticky note. Some writers like to check off events as they write about them to keep track of where they are in their stories. We encourage them not to cross through events because we want them to be able to read them the next day.

This strategy supports writers who struggle with processing and organization. It allows them to revise daily and add details to their stories. Revising daily is less overwhelming because they are doing it section by section, rather than taking an entire piece that they think is finished and having to go back and “fix it.” We find that their motivation is higher and their ability to revise is better.

Strategy 3: Type as They Write

We have found revision to be very hard for our writers who struggle with encoding and handwriting. They spend so much time and effort getting the words on the page in the first place that the thought of revision seems like a bad joke. In addition, many of them cannot read what they wrote by hand the previous day, so they cannot even begin to enter the process of revision. And when they cannot read it, they may feel embarrassed by their writing.

Rather than waiting until they are finished with them, we type these students’ pieces as they write. It doesn’t take us any longer in the end, and the payoff has been huge. We have always taught our students to begin each writing workshop by rereading their current pieces. These students can now do just that! They can read what they wrote, and their writing “looks” good to them. They immediately view themselves differently as writers. They also have a much easier time revising their pieces, since they can read and make sense of them. We find these students are motivated to mark up the pages with changes and additional details. Now that they know that adding more ideas doesn’t mean adding a ton of work for themselves, they’re more inclined to write exactly what they want to say.

A lot of focus on mechanics and accuracy gets in the way of struggling writers’ ability to think about the content and craft of their writing. Allowing them to reenter their pieces each day without having to think about mechanics gives them the ability to focus on content and craft. They can now enjoy thinking about leads, character development, dialogue, and other craft elements as they revise what they wrote the previous day. They are still writing each day on their own, but when they go to revise, they are using a typed draft. This process also allows them to work with peers more easily since now both the writer and the peer can read the draft. In the past, these students often resisted peer collaboration because they were embarrassed that they could not read their own writing.

These three techniques aren’t new or revolutionary, but they have certainly stood the test of time in helping struggling writers.