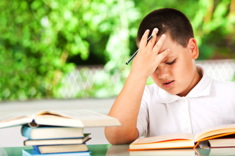

My eight-year-old son struggled while learning to read. The process of understanding how to figure out unfamiliar words on the page was painful. I felt that I had done everything a parent should do to support him: I read aloud to him frequently, made stories exciting, took him on all sorts of trips and adventures to build his schema, and modeled my own love of reading and writing. Yet, despite these efforts, my little boy struggled to decipher the printed word. After finding a great tutor and calming down, I realized that through helping him learn to read, I had learned some important strategies for motivating struggling readers in school.

Lesson 1: Focus on the Student’s Passions

As we know, students who are behind typically do not enjoy reading books that are at their “just-right” level. Many of these children know that they are behind their peers, and they feel frustrated. Their reading interests and cognitive level are well beyond the ideas and concepts in the simple books they need to practice. However, I have found that if I focus the students’ reading around his or her passions, some of this resistance disappears. Rosalie Fink studied successful adults who struggled learning to read, and found that many of them read and reread books in one subject area when they were children; this consistent reading about one particular topic helped them significantly. To support our struggling readers at school, we need to help them find their passions and provide them with lots of different texts in those areas. Texts that focus on one topic enable the struggling reader to rely heavily on background knowledge about a topic and thus make the reading process more accessible.

In second grade my son was passionate about Pokémon . . . Believe me, this would not have been my first choice of text for him. However, I found a few Pokémon books at a “just-right” level, and he read and reread them. I also read aloud many Pokémon Junior books that were slightly more difficult so that he could read these texts on his own in future months.

In the classroom, we can help children find their passions and then help them read just-right text in that area. In schools, I chat with students about their interests and hobbies, and I talk with the specialist teachers (music, art, and P.E.) and family members to learn more about the students’ interests. Once I know a bit more about the child, I organize books/texts into a topic basket and put that student in charge of caring for it. He or she adds books to the basket and tells other students about these wonderful texts. Here are a few examples of some topics/passion baskets, with examples of how certain texts in each were accessed by the reader:

Dragons and Mythical Creatures

- Poems from Jack Prelutsky—Read and reread select poems

- Dragon series—Dav Pilkey

- The Dragon Slayer series—Listened to first book on tape and then the student reread it several times

Arts and Crafts Projects

- Halloween craft books

- How to make pop-up books

- Craft ideas from the Family Fun website—Student watches the video and then reads the directions

Joke Books/Funny Stories

- Read and reread easy joke books

- Sponge Bob joke series

- Listened to the Diary of a Wimpy Kid

Cartoon/Action Hero Books

- Pokémon—Togepi Springs into Action

- Pokémon—Pikachu in Love

- Scooby-Doo—rebus stories

- Pokémon Junior early chapter books—read aloud

Lesson 2: The Importance of Reading Projects for Struggling Readers

Many struggling readers want and need to feel empowered and helpful to others, and reading to a younger child can help them achieve those goals. During reading workshop the struggling reader reads and rereads several “easy” books that they think the younger student will enjoy. I teach the older student how to read the book with expression and how to hold the book and read it like a teacher. Once they have practiced many times, the student spends 10 minutes reading the book to one student in a classroom of younger students. I recently worked with a 13-year-old student who actually practiced many Dr. Seuss books again and again with enthusiasm. This is a win-win project for everyone. The younger student hears wonderful literature and sees a model of an older student reading, and the older student feels successful. This reading project can be set up as a weekly meeting between the older and younger student so that they both can look forward to seeing each other on a regular basis.

I often ask my struggling readers if they would be willing to create books on tape for the listening centers for the kindergarten and first-grade classrooms. The students practice a story until they can read it with expression. They also work hard to remember to either ring a chime or say “beep” as they turn the pages so that the younger students will be able to follow along. Once a student creates a cassette, they listen to the tape to make sure the tape recording works well and then deliver it to a kindergarten or first-grade classroom. The children in these classrooms are always excited to hear an older child’s voice reading a story, and the older child is empowered as a true helper in the school. These projects, although simple, make an enormous difference in developing a child’s self-esteem. Most struggling readers know that they don’t read as well as their peers and therefore give up on learning. We have found that these types of reading projects help children alter their sense of self so that they see that they have reading skills that can be shared with others.

Lesson 3: Teaching Struggling Readers to Schedule Reading Breaks

When I enter a classroom during independent reading time, it is sometimes easy to spot the struggling readers just by watching the children’s behaviors. These readers are often looking out the window, flipping pages, or playing with small gadgets in their pockets. When my son was in first grade, his teacher told me he was falling out of his chair on a regular basis during reading time. It is no surprise that struggling readers avoid reading independently—the task is difficult and therefore unpleasant. We have found that by teaching these students how to schedule their own quick breaks, they can remain focused for longer periods of time. When conferring with these students, we help them set goals and then determine an appropriate and acceptable break. One child decided that he would read one book and then take a minute to look out the window and then read another book. I taught the child how to put his books in order, just like a to-do list, and place a sticky note with the word break in his pile of books. This break schedule put the student in charge of his reading and helped him understand ways to manage his own learning.

Teaching struggling readers is a complicated process, yet while we are teaching them how to decode and comprehend, we must also think about how to motivate them. Many of these children have been failing for years and have given up on themselves. We as teachers can still uphold rigorous standards for these children while also helping them find their voice and passion as readers. Our most important goal is to motivate our struggling readers so that they continue to persevere despite their reading difficulties.

On a personal note, my son’s reading life is a little bit different now. Although he still has difficulty reading accurately, he now reads lots of different types of text. (No more Pokémon!) My greatest joy as a mom is that each night I have to beg my son to stop reading and go to sleep.