While discussing read-alouds with a middle school colleague recently, the topic of vocabulary came up. The question “How do you choose the vocabulary to introduce in your read-alouds?” came up. The answer is, we don’t. At least not all of them.

We know the traditional approach of assigning a list of words to write definitions and sentences that will be collected at the end of the week, book, unit, and so on. This approach to “teaching” vocabulary assumes that students will then be able to apply their knowledge of these words to help them understand the text.

We have several issues with the approach of assigning a list of words to be defined, and we think most teachers agree that it’s not the best practice, but let’s face it, it seems to be an efficient technique. “Here are the words that we think will be tricky for all of you. Define them and write sentences.” At the very least we can say that students have exposure to a word and may recognize it as familiar if they see it again.

But for one thing, we know that dictionary definitions are often copied by students without being understood, and sentences can be written without fully understanding the meaning of a word. Here’s one sentence that a colleague shared with us that came from an assignment like this:

The boy was standing in the park like a monotonous.

Not the understanding that we were hoping for! We know that kids will often approximate accuracy as they get to know a word better, but we don’t think that just writing a sentence and definition is the best way to help them get to know a word well.

Another approach—one we’ve used and will still use at times—is to choose words in a read-aloud ahead of time and then pause when we come to them to give students an opportunity to use strategies we’ve previously modeled to figure out word meanings in context.

A problem with this approach is that we can sometimes miss the mark when we choose all the vocabulary words for our students. We’re sometimes surprised by the words they know that we assumed they didn’t, and, of course, we’ve been surprised when our assumptions about the words they do know aren’t met. In a recent class discussion, we were surprised when our students seemed to understand the word racism but didn’t have a firm understanding of the word prejudice.

An Approach That Gives Students Ownership

An alternative approach that we’ve been testing out is to let students make some of the choices about which words we will discuss and explore in our read-aloud. Our hope when we began doing this was that this approach would help us stop at words or phrases that caused confusion for students rather than words that we predicted would be troublesome.

Before beginning, we assigned students the task of looking for “word gaps.” This is a term that we’ve borrowed from Kylene Beers and Robert Probst in Notice and Note. When looking for “word gaps,” students are responsible for using a silent signal to alert us to unknown or unusual words and phrases. Raising a hand has worked fine for us, but we had also considered having a flag for students to hold up as a visual.

The first time we tried this, we gave students our instructions and then waited. We waited as they glossed over words such as mandatory and diverge, words we would have predicted that they may have needed to discuss in order to better understand. We tried to trust the process and didn’t stop the read-aloud to insert our own thoughts. Instead, we raised our eyebrows and gave inquiring stares, and eventually we had a student who noticed our stares and raised his hand to share a word. What followed was an authentic discussion of the word stance. It turned out that a couple of students had a better understanding of the word and were able to provide some examples to the rest of the class. The discussion ended up improving the understanding of that part of the text for everyone.

Revising Our Approach

The next time we tried this strategy, we provided a little more structure. We again instructed students to raise their hands as a silent signal when they noticed a word or phrase that was new or used in an unusual way. But we also said we’d expect them to stop us at least three times during the read-aloud to give an objective number of words to look for.

We also had a student jot each word or phrase on an index card to be displayed on our word wall. On the card we included an example of the word in context, the part of speech, and a brief definition. This provided an ongoing visual of the word that we could refer to and students could reference. We know that students need multiple exposures to a word to become comfortable enough to make it a part of their reading, writing, and speaking vocabulary, and a word wall is our first step toward supporting multiple exposures to a word.

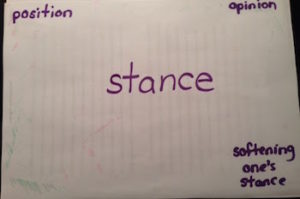

This is a vocabulary card made for a student-identified word. In the past, we’ve color-coded words by part of speech, but this year, we decided to make all words the same color, because many words can act as different parts of speech, depending on how they’re used in a sentence. We always put synonyms in the top corners, antonyms (if available) in the bottom left, and a short phrase that uses the word in the bottom right. We may try to make this phrase an idiom if applicable.

This is a vocabulary card made for a student-identified word. In the past, we’ve color-coded words by part of speech, but this year, we decided to make all words the same color, because many words can act as different parts of speech, depending on how they’re used in a sentence. We always put synonyms in the top corners, antonyms (if available) in the bottom left, and a short phrase that uses the word in the bottom right. We may try to make this phrase an idiom if applicable.

These little adjustments gave us a noticeable improvement in student engagement without the intense stares and raised eyebrows.

More Benefits

As we’ve continued using this approach, we’ve noticed several other things:

-

The discussions about these student-chosen words not only lend themselves to students understanding the text we are reading in a deeper way, but build vocabulary and background knowledge that can be carried to other texts. When students were asked to read a social studies document that spoke about “dissenters,” they were proud to report to us that they were able to bring their knowledge of this term with them to a new text. What better result than to know that the knowledge they’ve acquired is being applied elsewhere.

-

The discussions that we have explore words and phrases in different ways, including grammar. In a recent discussion about the word acquittal, we were able to discuss how the sentence structure helped us determine that the word was a noun.

-

We keep a Chromebook open in case we can’t figure out a word or phrase in context. This happened recently when a text alluded to a figure in history. We were not only able to speak about allusions as a literary device but do some quick research on the historical figure and discuss why the author might have named him in the text.

-

Our students now have an expanded definition of what vocabulary is, and we do as well. When we are reading, it’s not just unknown words that get in our way, but words that we see used in a new way. Recently, we were reading a text that referred to minorities. A student brought this word up because he didn’t understand how it was being used in the text. The student assumed that when the word minority was used, it always referred to a racial minority, which didn’t make sense in this text. But he hadn’t thought about the broader meaning when it refers to anything or anyone that is not part of the majority.

-

This approach allows peers to support each other. We are not in control of the background knowledge that students come to us with, but the structure of this approach allows students to share their knowledge, working similarly to the vocabulary part of reciprocal reading.

-

Last, and perhaps the most significant for us, is that when we choose vocabulary words for students, we are taking away their opportunity to monitor for understanding. They assume that we know the best and most important places to stop, so they aren’t always in the practice of recognizing and fixing confusion. This approach puts that responsibility squarely back into their hands and requires them to attend to where meaning breaks down. We frequently refer to our practice in read-alouds when we confer with students who are reading in their own independent reading books.

We plan to continue to test this approach to give students ownership of their vocabulary, and we are sure to make more adjustments along the way. Improving vocabulary instruction and making this work more student-centered is a task that will never end.