I have a confession to make: I’ve always struggled with incorporating vocabulary study into my high school English class. I’ve tried lots of different things over the years, but never felt like I hit on the perfect strategies. Some years I’ve spent a lot of time on vocabulary, and other years it has mostly fallen by the wayside. But last year, I was confronted by a startling revelation during a lesson on connotation: My students’ vocabularies are lacking, and I can’t ignore vocabulary study.

In this particular lesson, I was working with my 11th-grade students on seeing the connection between connotation and tone. I wanted them to notice how an author’s choice of words can add emotional undertone to a text. To illustrate this, I gave students sets of words with roughly the same meaning and asked them to talk about how the connotations, or emotional undertones, of the words differed. I was surprised to find that my students were completely unfamiliar with many of the words that I thought were somewhat common. One set of words consisted of tight, frugal, economical, miserly, thrifty, and penny-pinching. The group that was working with this set struggled because they were unfamiliar with half the words. They claimed to have never heard the words frugal, miserly, or penny-pinching. The point of the lesson was lost if my students were unfamiliar with many of the words.

Since then, I have tried to find ways to incorporate vocabulary study into my classroom that are both manageable and useful for my students and me. Here are some rules that form the foundation of vocabulary study in my classroom.

Think Small

In the past, I would give students long lists of vocabulary words in connection to a text we were reading in class. The students would dutifully define the words (or not), then read the text. But I never really saw them retaining the words or using the definitions to enhance their understanding of the text. Then I realized that maybe my students didn’t need to review every unfamiliar word in the text. Instead, could I just look for the unfamiliar words that would be most helpful in aiding their comprehension of the main points of the piece? Maybe the long vocabulary lists were just too much. I began paring my vocabulary lists for short stories, articles, and essays to just six words. Why six? Well, that was how many vocabulary square templates I could fit on one sheet of paper, but it turned out that six words were easily manageable for all of my students, no matter their ability level. I chose the words by asking myself these questions: Which words are essential to the understanding of this text? Where will meaning break down when students encounter an unfamiliar word?

For example, when reading Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado,” my students need to be familiar with the words redress, retribution, and impunity to fully understand the motivations and plans of the narrator. We spend a good deal of time discussing these words before reading the story, whereas other unfamiliar words, such as flambeaux, can easily be added as a footnote in the text. A word such as that is useful in the short term for adding a detail to our mental picture, but it isn’t necessary for getting to the heart of the story.

Substitute with Synonyms

Sometimes we encounter a text in which a lot more than six words are unfamiliar to the students. For example, my 12th-grade class was recently reading Jonathan Swift’s “A Modest Proposal,” and the combination of the writing style and abundance of unfamiliar words was making it challenging for many of them. Our purpose in reading this text was to understand Swift’s argument and his use of satire, but words such as raiment, fricassee, prodigious, and parsimony were preventing my students from doing that. As a class, we scanned the text and created a list of 35 unfamiliar words. Using both online and print thesauruses, we found one-word synonyms that we could easily substitute for the unfamiliar words. Synonyms we found for the above words were clothing, stew, enormous, and stinginess. My students actually wrote the synonyms above the unfamiliar words in their copies of the text, which made reading and comprehending much more fluent.

Make It Personal

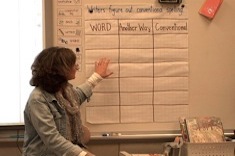

The story about the connotation lesson shows that I have sometimes assumed my students were familiar with words when in actuality they were not. On the flip side, I have also chosen six words to accompany a short story only to discover that the majority of the class was familiar with half of them. When it comes to vocabulary, it is important to find out what your students know. Before we start a new text, I have students complete a word sort. I make a list of any and all words that I think might pose a problem for them and ask them to simply put the words into categories such as “Never heard of it,” “I’ve seen it but don’t know a meaning,” or “I know it.” I use the word-sort charts found in Janet Allen’s Words, Words, Words: Teaching Vocabulary in Grades 4–12, and the process takes just a few minutes. Once I have assessed my students’ knowledge, I can decide which words to focus on as a class and which students will need additional support.

My students are always reading books independently, and this year I have, at times, asked them to create their own personal vocabulary lists by choosing new and interesting words from the books they are reading. They record these new words in their writer’s notebooks and work on incorporating them into their writing. When students are in control of the words they are studying, it is much more meaningful.

Assess Authentically

One of the things I am striving for with vocabulary words is transfer. In other words, I don’t want my students to simply memorize a list of words for a matching-style quiz and then promptly forget them. I want them to move beyond memorization and add new words to their lexicons. When I do give a quiz on vocabulary, I create tasks that require students to think and write about the word. For example, if one of our words was lassitude, I might ask, “Tell me what activities give you a feeling of lassitude and explain why.” Or I might tie the vocabulary word to comprehension of a text. While reading Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience,” we were studying the word expedient. This was a task on a quiz about the essay: “Thoreau said, ‘Government is at best but an expedient; but most governments are usually, and all governments are sometimes, inexpedient.’ Explain what this means.”

An assessment that is a great favorite with my students is to choose a number of the vocabulary words and use them to create a short story. The idea is simple: See where your imagination can take you, although I usually add the restriction that they cannot use more than two vocabulary words within one sentence. I have been blown away by the creativity that comes out of this activity. It also gives me a good indication of whether the students understand how to use the word in a different context, which brings me to my last rule:

Don’t Overlook Parts of Speech

One thing that I noticed when my students began incorporating vocabulary words into their writing is that they were sometimes using them incorrectly. They were getting the meanings right, but the parts of speech were tripping them up. For instance, they were adding -ing to nouns and using them as verbs. I realized that I needed to do a quick review of how the different parts of speech function within a sentence. Using simple sentences to illustrate my points, I reviewed where you find nouns, verbs, adjectives, and adverbs working within a sentence. This seems like elementary knowledge, but it really helped my students incorporate new words correctly.

Another way that I help my students remember parts of speech is to create a word wall in which the words are organized into categories: nouns in one category, verbs in another, and so on. This is a quick visual reference for students as they work on a piece of writing.

If, like me, vocabulary study has made you feel frustrated or overwhelmed, try incorporating one or more of these simple ideas. After years of struggling with how to best incorporate vocabulary study into my classroom, these were the simple rules with which I started afresh. I am still learning and discovering what works best for my students, but these steps created a strong base upon which to build.