I know. That title kind of makes your heart skip a beat, doesn't it? Imagine how I felt when I read it in a National Council of Teachers of English conference program book, describing a session given by Ralph Fletcher. I went to the session filled with tremendous trepidation. I was so afraid that Ralph would say that we should not use mentor texts anymore. The good news is that he didn't. The bad news is that he said maybe we shouldn't be doing this:

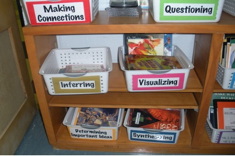

Are there book bins like this in your school's bookroom? In your classroom? I bet somebody spent a lot of time selecting and gathering the books to put in those bins. I know, because I've helped with that task. It took weeks! Reading professional books and articles, ordering the books, labeling the books — it was a lot of work. Ralph said that the trouble with those bins is that they cause us to limit the way we use books. Once a book is labeled as a "synthesizing book," it is hard for us to even consider any other possible use. He said that well-written books are "treasure troves filled with limitless possibilities" for wonderful lessons.

The Possibilities of One Mentor Text

I decided to try it out. I took out my all-time favorite, can't fail, mentor text: The Relatives Came (Rylant, 1985). I have used this book with kindergarteners, middle school students, high school students, graduate students, and parents. Every single time, it generated lots of animated talk, occasionally a few tears, and always wonderful writing. Apparently, having relatives come for a visit or being a visiting relative is a universal experience. It cuts across all ages and socio-economic levels. I haven't met anyone who hasn't experienced it. That makes The Relatives Came

the perfect book for teaching about making text-to-self connections, right?

Of course that's right. But when I reread the book with an open mind, I found so much more:

1. Lead: "It was the summer of the year when the relatives came." A classic opener, giving a little information about the setting. It makes you wonder, "What happened that summer?" Then you are hooked. You have to find out! You must read on. That is what good leads do – make you want to read to find out more.

2. Ending: "And when they were finally home in Virginia, they crawled into silent, soft beds and dreamed about next summer." What a comforting and satisfying ending. Rylant literally put the story to bed. Many young writers abruptly end pieces. Sometimes they help the reader out by adding "The End." Show them how to ease the reader into the conclusion.

3. Memoir Writing: This book is one of Cynthia Rylant's memoirs. It shows that a memoir is a small slice of an author's life – not the whole thing. Our students will learn that their lives are filled with memoirs, even if they are only six years old.

4. Internal Thoughts: It is a useful technique to allow the reader to know what the characters are thinking. It is also critical information to help young readers better comprehend stories. "…they thought about their dark purple grapes waiting at home in Virginia. But they thought about us, too. Missing them. And they missed us."

5. Transition Words: "Then it was hugging time"; "Then it was into the house…"; "And finally after a big supper…there was quiet talk." Rylant didn't use fancy transition words, but the simple words she selected propel the reader through the first day of the visit.

6. Visualizing: "They had an old station wagon that smelled like a real car, and in it they put an ice chest full of soda pop and some boxes of crackers and some bologna sandwiches." Can't you just see that station wagon filled with people, suitcases, food and the ice chest? Rylant even tells us what the station wagon smelled like. Stephen Gammel's gorgeous illustrations are a blessing and a curse. Once we see what Gammel visualized, our mental images pale in comparison. Luckily, he did not illustrate that passage. Invite students to do it.

7. Sentence Variety: This book has a wonderful variety of sentences. Some are only three words long – "We fell asleep." Some are complex sentences, with two commas and a dash that fill up an entire page. It is the kind of text you want to share with students who write pieces made up exclusively of five-word sentences that start with "I."

8. Voice: Instead of saying, "The relatives hugged us a lot," Rylant writes, "You'd have to go through at least four different hugs to get from the kitchen to the front room. Those relatives!"

9. Beginning-Middle-End: This a good book for teaching simple story structure. There is a clear beginning, middle, and end.

10. Circular Story Structure: The structure is just like If You Give a Mouse a Cookie! (Bond, 1985). You might have some writers who are ready for different kinds of narrative structures.

That's ten different teaching points, not counting text-to-self connections. I'm sure that there are even more. I have two other cautions about using mentor texts. Ideally, mentor texts are well-loved books that your students have heard, read, and reread. Resist using them for teaching until your students have heard (read) the books at least twice. Finally, don't be selfish. It is very common for a teacher to have his or her favorite mentor text in a book bin on a shelf behind his or her desk. Students may not be allowed to read it. If you are afraid of losing track of your teaching books, get another copy of each one, so your students can also enjoy these treasures. With these simple cautions in mind, take out your favorite mentor texts and figure out what else you can teach from them.