Have you had good chocolate and then tried really excellent chocolate? Were you ever able to go back to the just-good chocolate? Yeah, me neither. That’s what happened when I went on a tour of the Theo Chocolate Factory in Seattle. Our one-hour tour started off in a makeshift classroom, where we learned what is meant by organic fair trade chocolate and previewed the bean-to-bar process. On our journey through the factory, my family and I got to touch cacao pods, see the huge roasters and mills, check out the molding and packaging process, and end up in the Confection Kitchen where we sampled goods like caramels and ganaches. We were feeling a bit “theobrominated,” which refers to the mild stimulant in chocolate related to caffeine, as we staggered into the gift shop.

At the end of the tour I didn’t ask my high school son to create a poster of the bean-to-bar journey or my middle school daughter to write a compare/contrast essay of Theo’s vs. Hershey’s chocolate. I especially didn’t ask my third-grade daughter to fill in a graphic organizer with preset questions. Why? Obviously it was a fun family outing, but beyond that we didn’t create any products because research and learning was the whole point. It was the beginning and end of the project. We walked in wanting to know more about chocolate, and we left with answers to our questions and new questions to consider. This is research.

Participate, Recall, and Gather

Using first grade as our example in the Common Core State Standards and focusing on the “Research to Build and Present Knowledge” section, we see three verbs that point us toward what students need to do: participate, recall and gather.

Participate in what? Shared research and writing projects. Recall what? Information from experiences. Gather what? Information from provided sources.

If we go beyond the writing standards, and look at informational reading as well as speaking and listening standards we see more verbs: read, ask, answer, build on, and describe. What you may notice these standards have in common is a focus on process, not product. The standards don’t include the expectations to “create a crossword with new vocabulary” or “cover a cereal box with facts” or even “write an acrostic poem with the name of your animal and what you learned.”

Proof of Learning

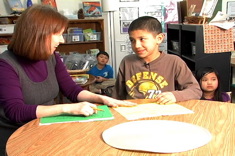

My colleague Kellie explained to me that what she felt most nervous about was accountability.

“If I don’t have them do a project like I did last year, how will I have proof that they learned anything?” she asked.

“Talk to me about last year’s project and how it gave you proof,” I said.

She rolled her eyes and smiled a little. “Well, actually the proof it gave me was that even though I asked parents not to help, they did anyway.”

“Sounds familiar,” I smiled back at her. “If we look back at the standards, the requirements are to ‘participate in shared research and writing,’ ‘recall information from experiences,’ and ‘gather information from provided sources.’ What proof do you already have that gets at that?”

Kellie explained, “They have their notebooks and we have those charts where each student put sticky notes. I guess that gets at the participating and gathering, but I don’t know what they recall from their research.”

We decided to ask students. Kellie met with about six students a day during workshop and started with this prompt, “Tell me what you are learning as a researcher.” She then took notes about students’ questions, facts, and responses to resources. In our coaching conversation, we’d anticipated that some students would use vague words like “it,” “stuff,” and “things” while others would say, “Naked Mole Rat,” “ignition,” and “tentacles.” A plus for specific terms and a minus for lack of specific terms was Kellie’s key code in her notes. In addition, we knew some students would offer limited information and shrug when she asked, “And how do you know that?” Others might give a thorough recall and offer evidence. Again, Kellie just noted the presence or absence of evidence during the recall.

At the end of the week, Kellie emailed to share that she’d assessed all her students. She knew which kids needed some specific work on vocabulary, and those she wanted to pull into small groups to help them learn to recall with more detail. It was no small thing that Kellie had used the word “assessed” to describe the process she’d gone through. Through her standards, anticipation, and planning how to record, Kellie found her proof.

Kellie added, “Spring conferences are coming up and I have so much more to say about their research.”

When I asked her how her thinking about accountability in research had shifted she explained, “I will continue to have children do projects to express their learning, but it’s such a relief to know I don’t have to do them each time we research something. I feel like research can be a smaller thing than it has been for me in the past, and I can feel more sure of what they are learning. I see how research can fit more naturally into what we are doing, instead of being a single unit in the spring.”