We started a recent conference with Kyra by asking a typical question:

“What are you working on in your writing?”

Kyra pointed to her memoir and responded, “I’m revising for spelling.”

Confusing revision with editing is common. In fact, it’s not just the name of the process; even when students are comfortable with the difference between revision and editing, their revisions are often cursory, without major changes to their original drafts. It’s clear that most students feel more comfortable and are more apt to edit their writing than to do big-scale revisions, because it feels easier and more manageable.

But revision, or the literal meaning, re-seeing, is necessary. It may be the most important work of writing. It’s the part of the process when we try to figure out the very best words and put them in the best order to get our message across. If that sounds hard, it’s because it is hard. A task like that doesn’t get done the first time around. Writers must ask themselves which details need to stay and which aren’t needed. What is the best order in which to put these words? Is there a word that would work better?

To make the process of revising more appealing, we explicitly model revision in our writing during minilessons, teaching students practical ways to make room for large-scale revisions that leave their original words intact until they’re sure they have something they’d like to replace them with.

Practical strategies: Some of our older students use carets or the margins to add small bits of information. Both of these strategies are great for quick changes, but to move beyond small-scale, cursory changes and open up the possibilities and space for revision, we demonstrate a couple of other strategies for students.

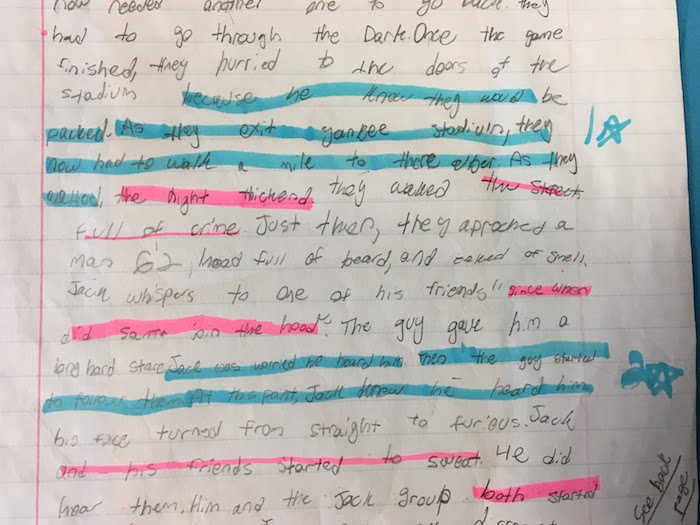

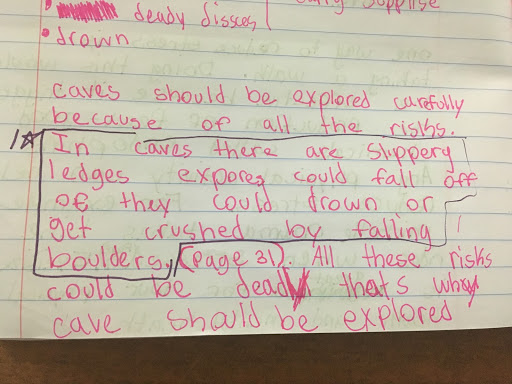

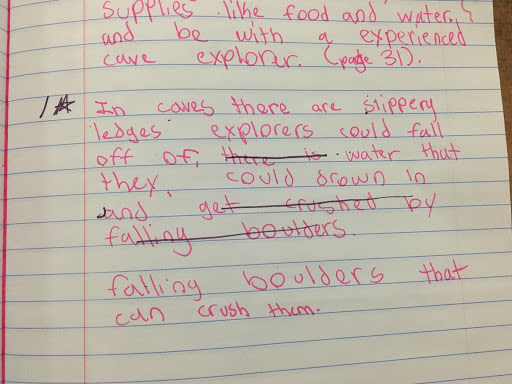

- Sticky notes: As students get older, we phase out the strips of paper in our writing center and replace them with large sticky notes. Our students box out or highlight the part being revised and mark the part with a number. Then they grab a large sticky note and write that same number at the top before revising that section of text. The sticky note usually goes on the back of the draft. Students will end up with a few numbered sticky notes with each of their revisions. When it’s time to publish, they’ll look for the corresponding sticky note each time they see a number, and insert their revision.

2. Separate revision paper: Sometimes students prefer to have a revision page rather than multiple sticky notes. When they revise, they follow the same process of boxing out and numbering parts to revise. Then they write the corresponding number on their revision page so all revisions are in one place, ready for typing, when it’s time to publish.

3. Writer’s notebook: Our students draft on paper outside their notebooks, but we find that we head back to our notebooks for some revisions. In particular, we find notebooks to be a great place for students to try out multiple ways of writing a lead or ending before choosing “the one.”

4. Digital revision: We’ve observed that when students are drafting on a Google Doc rather than on paper, they don’t always find it easier to make revisions. Rather, they sometimes view their writing as “complete” because it doesn’t have the “messiness” of a written draft. We use the comment feature to leave feedback for students, but we also show them how to highlight the text they’re revising (similar to the “boxing out” shown above) and write revisions in the comment box before making the change in their document. That way they can try out how it sounds before committing to the change.

When we look at a student’s final published piece, we want to see the whole process, which includes revision. Students hand in their published writing with their original drafts and sticky notes or paper with revision. If the revision was done digitally, we’ll ask students to highlight the revisions or change the font color. That makes it easy for us to see writing growth through revision, and it’s motivating for students to see their revisions stand out in this way.

Making the progression of writing from a first draft to a finished piece visible is oddly rewarding, similar to the feeling we get when we check items off a to-do list. We’ve found that showing students some simple but practical ways to revise motivates them to skip the cursory changes and make big revisions.