Nobody has ever told the language arts teachers at my middle school to stop reading aloud to students, but administrators have questioned us about the practice. As a result of being challenged, many teachers have begun to feel pressure to stop reading aloud altogether. In fact, if an administrator pops in for a visit when a read aloud is happening, you can bet the teacher will quickly shift to another activity. Some of us have even abandoned whole-class novel studies in an effort to spend less instructional time reading aloud.

In reality, what administrators are questioning is not the practice of reading aloud, but rigor. They wonder whether students not doing the reading means they’re are not being challenged as readers.

Rather than dumping reading aloud in favor of something that may be more easily perceived as rigorous, I decided to become more intentional, so that I am ready for a conversation about the instructional decision to read aloud to my eighth graders. If an administrator pops in, not only do I happily continue reading, but I welcome the conversation that is sure to follow the visit.

Introducing the Read Aloud

Recently, I read aloud Matt de la Peña’s picture book Love. Students had previously read and analyzed another of his picture books, Last Stop on Market Street, and his short story “How to Turn an Everyday, Ordinary Hoop Court into a Place of Higher Learning and You at the Podium” from Ellen Oh’s anthology Flying Lessons and Other Stories. Their previous admiration of de la Peña’s work provided an easy invitation to enjoy Love.

Having discussed Love with a colleague who admitted to struggling to make sense of the book, I anticipated some confusion over the format. So, before reading I told students that the book is essentially an illustrated poem, rather than the traditional narrative storyline one might expect when opening a picture book. Like the short story about a hoop court, I explained, the text is written in second person about “you,” the reader. However, unlike the short story, the “you” in Love is not a single you, but rather you and you and you. I went on to point out that the illustrations on each page would shift from one character to another to another rather than follow the narrative of a single character from page to page.

Getting Students Thinking

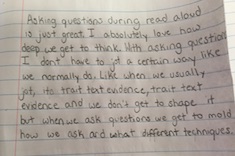

Although an observer might guess that I provided this background to make the read aloud easier for students, the real reason is quite the opposite. I did not want students to spend their energy on the simpler task of comprehending the text; rather I wanted them to focus their energy on the more complex thinking required for analysis. The last thing I told students before reading the text is that something about this text had been challenged and almost caused a change before publication. I asked them to think about what someone might have found worthy of challenge.

Although on the surface this was a simple request, it prompted a high level of cognitive participation on the part of the students. Rather than sitting passively, I was asking them to think from someone else’s perspective, to question the text, and even to connect the text being read aloud to the other texts they had recently read. The foundation for this level of challenge is that my selection of the book Love was not random. It was not simply based on how much I admire the craft of the book. I had encountered Matt de la Peña’s article “Why We Shouldn’t Shield Children from Darkness” at Time.com in the midst of our class study of the effects of fictional violence on children. When I read about the challenge made against the illustration depicting the aftermath of a violent domestic dispute between parents, I knew Love would be a perfect resource for instruction.

During the first reading of the picture book, one of my students blurted out, “Well, that took a dark turn!” in response to the page immediately after the domestic dispute. This illustration revealed a family huddled in front of a television set, and the text read, “One day you find your family huddled around the TV, but when you ask what happened, they answer with silence and shift between you and the screen.” Other students nodded and murmured their agreement. Although they reacted to the implication of a tragic televised newscast, students did not seem the least bit affected by the previous scene of domestic violence.

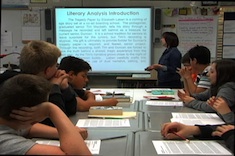

Discussing the Read Aloud

Upon finishing the read aloud, I repeated my prompt, asking what students thought someone might have found troubling enough about the book to challenge it. One student suggested that perhaps it had to do with opposing religious views, pointing out that the television scene had contained a cross and an image of Jesus hanging on the wall, whereas another image featured a young girl wearing a hijab. Other students seemed stumped.

I turned to the image that was the target of the challenge. Upon taking a second look, the light bulbs turning on in students’ minds resulted in murmurs of discovery. Students began pointing out how scared the child hiding, huddled under the piano, looked. They noticed the overturned armchair and lamp. Some guessed at whether the father walking away in the image meant he was walking out, leaving the family. One student gasped when he noticed the nearly empty glass sitting on the piano. I asked him to explain what he was thinking, and he reluctantly said he thought it might indicate that the dad is an alcoholic, which caused another student to consider whether the fact that the mother was covering her face with her hands could mean she had been hit rather than that she was just crying.

Digging Deeper

I barely had to say a word as the students dug into deeper analysis of the text. Finally, I asked whether they believed the illustration was appropriate to include in a book meant for young children. Their responses were overwhelmingly in favor of the illustration. Most students said they think children should be told the truth and noted that the illustration was telling a hard truth about life. One student explained that it might help a child understand what a friend was going through. Another student suggested that it could cause families to have conversations that they should have been having anyway.

The entire read aloud, including before, during, and after reading discussion, took no more than 10 minutes. The result was that students developed their own beliefs about the text.

Connecting the Read Aloud to a Unit of Study

If questioned by an administrator, I would be able to explain that I did not choose to read aloud Love as an isolated activity, or to fill time. I did not choose a book that would be easy, nor did I choose to read it aloud because it was just easier for me to do so. I chose this read aloud intentionally, as leverage for the work that followed.

Students moved from having the picture book read aloud to them to independently reading nonfiction articles on the effects of fictional violence, which served as a bit of research to help them develop a claim for an argumentative essay they will be writing. The analysis of Love set students up to read the articles with a greater purpose. They were more deeply engaged in reading independently as a result of the read aloud.

Though it may seem simple on the surface, reading aloud a picture book can be the perfect way to inspire students to engage in higher-order thinking. Careful selection of a text related to a social issue or topic of study can launch a unit and help sustain deep analysis. And that is worth talking about.