It can be challenging to engage children in our minilessons. Sometimes those challenges arise because of behavior issues—there’s the syndrome when as soon as you address one student’s behavior, another student needs redirection. Sometimes the challenges are the result of compliance where students have figured out that all they really need to do is sit quietly, and minilesson time passes. However, if you ask those students what the lesson was about, you get blank stares.

Although the best way to improve student engagement is to keep minilessons short, I have been working on a few other tricks to increase student engagement during minilessons. If you teach workshop in the classic connection–teaching point–active engagement–link format, these ideas would be within the active engagement component of a minilesson.

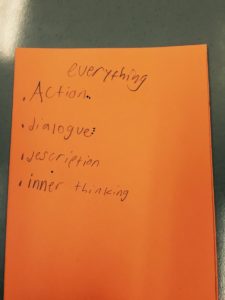

During the minilesson, think about how to give students something to do that is more than a turn-and-talk. I love turn-and-talks. They just can’t be the only form of active engagement during lessons. Think about tasks students can do that require them to produce something. For example, when I taught a fifth-grade class about the different ways to elaborate in a narrative piece of writing, I had them create their own tools.

During the minilesson, think about how to give students something to do that is more than a turn-and-talk. I love turn-and-talks. They just can’t be the only form of active engagement during lessons. Think about tasks students can do that require them to produce something. For example, when I taught a fifth-grade class about the different ways to elaborate in a narrative piece of writing, I had them create their own tools.

In this example, students were going to use the card to record when they used each strategy in their own work.

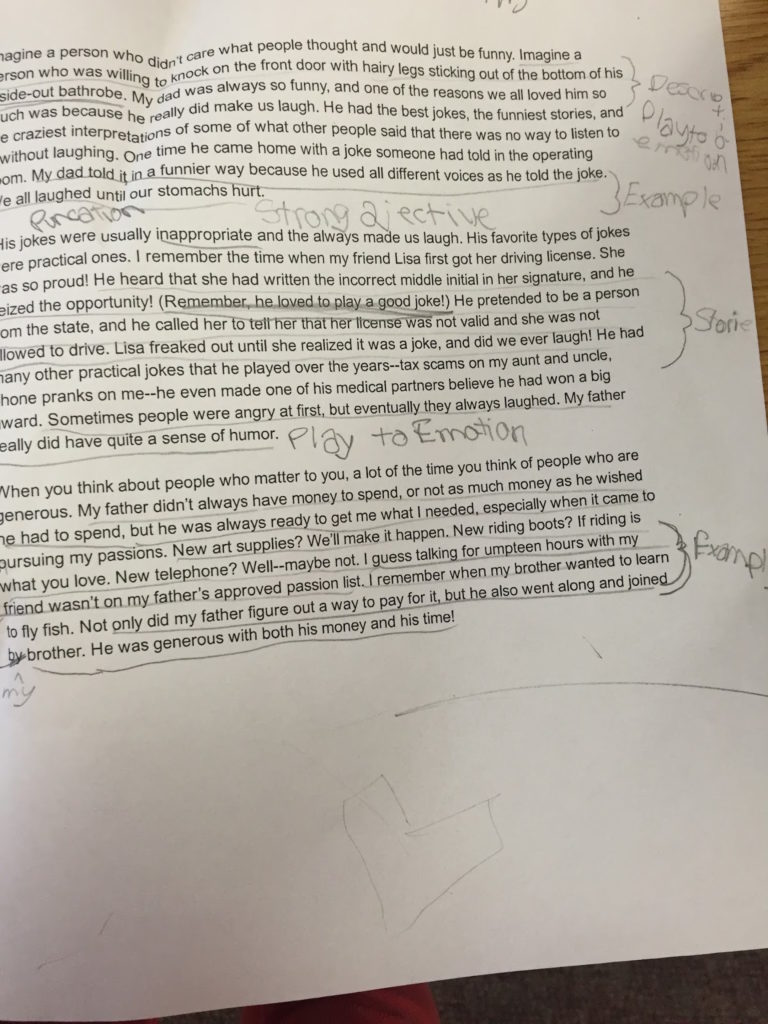

Give students a text that they are to mark up. In this instance, this task was the second of two lessons about the variety of ways writers can elaborate in opinion writing. I had them bring clipboards and pencils to the rug, and challenged them to find and name those examples in a piece of my own writing. My active engagement lasted longer than usual—I set my timer for five minutes—but the time was well spent, and I was able to push some of the usual nonengaged suspects to mark up their papers.

Give students a text that they are to mark up. In this instance, this task was the second of two lessons about the variety of ways writers can elaborate in opinion writing. I had them bring clipboards and pencils to the rug, and challenged them to find and name those examples in a piece of my own writing. My active engagement lasted longer than usual—I set my timer for five minutes—but the time was well spent, and I was able to push some of the usual nonengaged suspects to mark up their papers.

As an alternative to the above strategy, if you are in a situation where you have an extra adult in the room or if you are coaching a teacher, consider sharing student ideas publicly. In this situation, we had students notice the craft moves in my demonstration paragraphs and name them to me, and then the classroom teacher highlighted and made comments, giving the student credit on the document. We could then share this document in the class’s Google Classroom so they could refer to it.

Include a goal-setting element within the active engagement. During the lesson of the following example, I was teaching students to push their thinking by using prompts. I presented the following chart, and then I had students write down three or four goals and set an intention to include them in their freewriting for the workshop. Because I told them right up front that they would have a task to complete before they headed off to write, they paid more attention.

Let students know that they will have the opportunity to add their names or initials to the chart. In this example, we taught third-grade students about the different ways to orient readers in the beginning of narrative writing. In this lesson, we shared the beginning of Owl Moon by Jane Yolen, as well as a beginning the classroom teacher had written, and pointed out the craft moves just on the first page. Then throughout the minilesson, students were invited to add their initials to the chart if they tried those craft moves in their own writing. Although other factors may have been at play, one reason engagement was high in the minilesson was that students wanted to make sure their initials could be on display.

I once heard the wise words that engagement is the most powerful form of behavior management. Over and over again, I see behavior improve when instruction flows, relates, and captivates. Students learn when they are paying attention.