This is not a trick question: When is a multiple choice vocabulary test fun and motivating? The answer: A multiple choice vocabulary test is fun when it is a game on the computer that gives you harder words when you get one right and easier words when you miss one. It is a game that donates rice to the world’s hungry every time you get a definition right. It’s called Free Rice, and if you haven’t played yet, go now and give it a try. We’ll talk about classroom applications when you get back:

Motivation

As an adult playing Free Rice, I am very motivated by the vocabulary level they assign me based on the words I get right or wrong. I am so motivated by vocabulary level that I often take the time to go to the dictionary rather than risk getting a word wrong.

My students, however, are motivated by the rice. There are a few who start out using the dictionary. But because the outcome of missing a word is positive rather than negative (getting a word they are more likely to know), my fourth graders wind up playing at an average vocabulary level of 3.9. In one half an hour of play, they earned an average of 4423 grains of rice each. Who wouldn’t choose to focus on a “score” in the thousands rather than in single digits?

Strategies

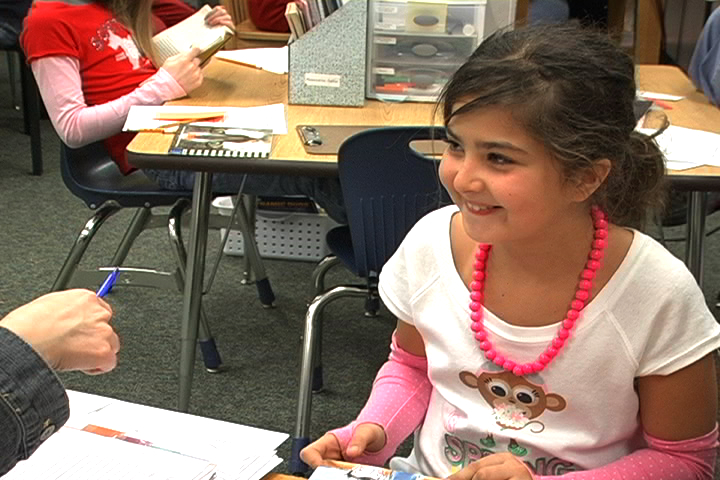

One of the most obvious test-taking strategies that this game reinforces is the importance of reading every choice before deciding on an answer. As I stood behind my students watching them play, I witnessed them using the strategy of process of elimination as well. The strategy I was most anxious to observe — using the word’s root to choose the definition — was a bit more elusive. Lisa knew that knowledgeable meant learned because she found the root knowledge and chose the definition learn. Dean saw hard in the word hardening and solid in the definition solidification and knew they went together. Erika used the mac in macaroni to choose pasta as the definition.

Differentiation

Rather than frustrate a student who I knew would play successfully on a level 1 or 2 by having him miss enough words to get that low, I quickly “set up” the game for him by deliberately missing words until the game had reached level 5 and the words were more likely to be one or two syllables long. Differentiation is, however, inherent in the game because it levels the words you are given based on how many you get right or wrong.

Assessment

My students played Free Rice for about 30 minutes. As they worked, I circulated around the lab, questioning small groups about the strategies they were using, new words they had learned and any times they had used root words to find the definition. This part of my assessment was anecdotal.

Near the end of the session, I noted the level on which each child was playing (shown on the screen), and when we were done, each child called out the number of grains of rice s/he had earned. These two pieces of data gave me some interesting information about each child and about the class as a whole. The average vocabulary level my 4th graders played at was 3.9, with a range of levels between 9 and 1. The number of grains of rice earned ranged from 1160 to 8100.

For the most part, I was not surprised by the level at which each child played. It was much more interesting to look at a child’s level along with his/her grains of rice earned. Here are some examples:

LEVEL — NUMBER OF GRAINS 9 ———– 5680 5 ———– 8100

What was the level 5 student doing differently that allowed her to earn so many more grains? Was she playing faster and with better focus? Did the level 9 student just have a few more lucky guesses than she did?

LEVEL — NUMBER OF GRAINS 1 ———— 6140 9 ———— 5680

The contrast here is a testimony to the power of the leveling capacity of the game. Even though these levels represent the two ends of the spectrum in my classroom, the two students were able to earn about the same amount of rice.

There are plenty of games and activities for the regular classroom that give students practice building words and give us opportunities to teach and observe word-building strategies: Boggle, Making Words, Making Big Words, just to name a few.

Word study on computers is a win-win proposition. Kids love to work when it feels like play, and you get to observe them in a fresh new way as they use the strategies you’ve taught or — even better — as they invent new strategies for solving and making words.