“I’ve got that issue, too!” Max exclaimed, and jotted dogs in the skate park on the next line on a page in his writing notebook.

“Those dogs are running all over the town,” said Marah. “It’s totally a local issue, right?” Marah looked at me from across the circle.

“Yes, because it is something that is happening in our town. It’s considered a local issue,” I affirmed.

“It feels personal to me,” Max said, and the class chuckled, remembering the story Max told at the start of class about the dogs chewing his skateboard until it was splintered.

This share session conversation happened on a day when we were shifting to nonnarrative writing. Sometimes, writing notebooks lie forgotten and dusty when units of study move toward informational and persuasive genres. I was determined not to let this happen.

My notebook is a power tool in my writing life, which is mostly nonnarrative. I could not survive without my writing notebook, because it allows me to discover the topics I care about and collect ideas to learn more and solidify my thinking. When I’m writing persuasively, my notebook becomes the place I find my voice and learn to balance facts and emotions as I attempt to change hearts and minds with my words.

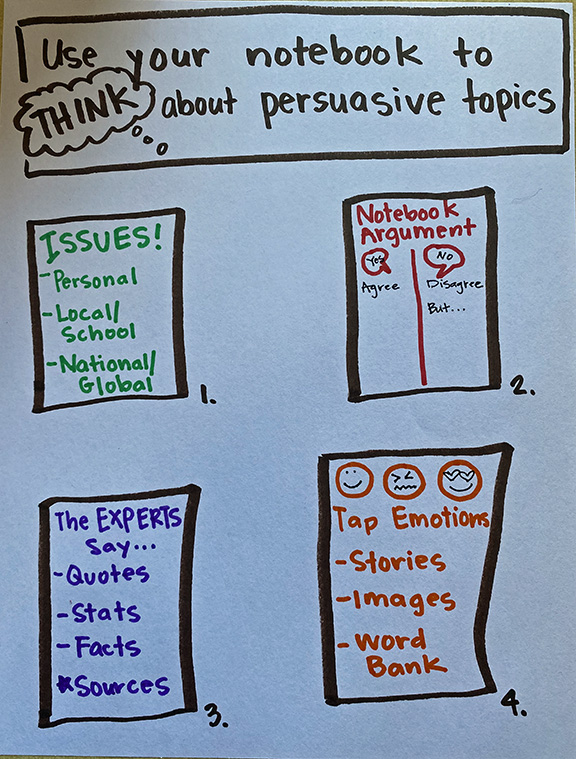

Here are four notebook pages that allow students to do the same.

Issues!

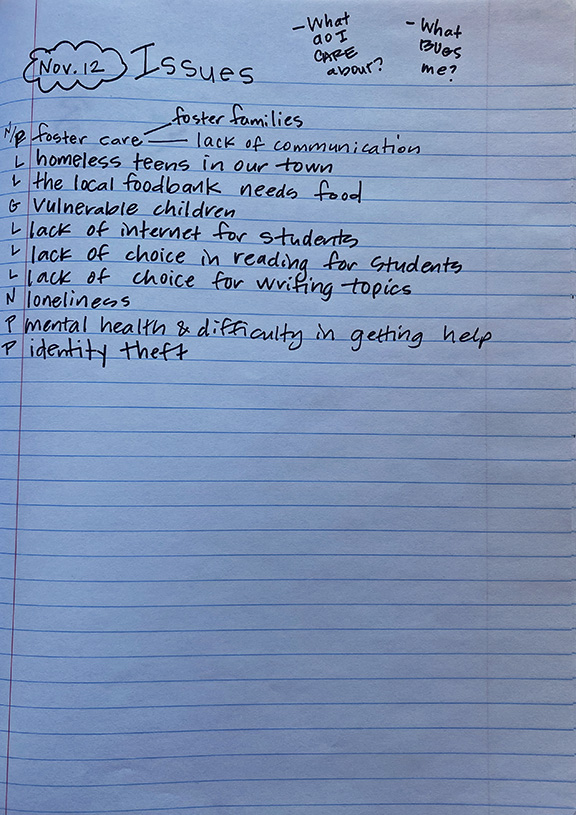

An “Issues” page prompts students to be specific about the things they care about. Encourage students to generate a robust list by considering personal, local, and global issues.

I use my own notebook page as an example. In the margin I have coded each item on my list according to the kind of issue it is. Also, the items on my list are phrases, and sometimes just a couple of words. Students will do the same thing. By using my notebook page, I’m able to model the initial general thinking and then go back and be more specific. The first item on my list, foster care, is very general. I then returned (during the minilesson) and noted more specific issues I have with foster care.

When conferring with students, it is likely they will collect many issues from one area of their lives. It is common for kids to be able to find lots of personal issues and some school issues, but they may need encouragement in considering national or global issues they care about. They will also need to do the work of naming specific issues. A hearty list will give students many opportunities to try out different topics to find one they care about deeply enough to put time and energy into writing.

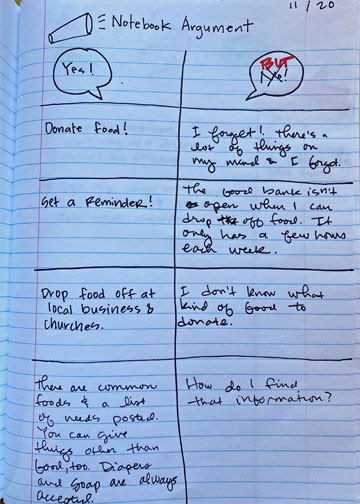

Notebook Argument

As humans, we often find it difficult to see the other side of an argument. For example, because I feel so strongly about foster care, I used to have a difficult time understanding why people with extra bedrooms and space in their homes do not open their doors to a foster child. Yet to write well about a topic, I must understand the other side. In this case, a notebook argument is often helpful.

For some topics, like vaping, this entry can be tricky. No one is going to say, “People should vape!” Yet, according to the Centers for Disease Control’s Fast Fact Sheet on Smoking and Tobacco Use, nearly 2000 people younger than 18 smoke their first cigarette each day. As students navigate a notebook argument, they find the nuances of the issues and plant seeds for growing a counterargument.

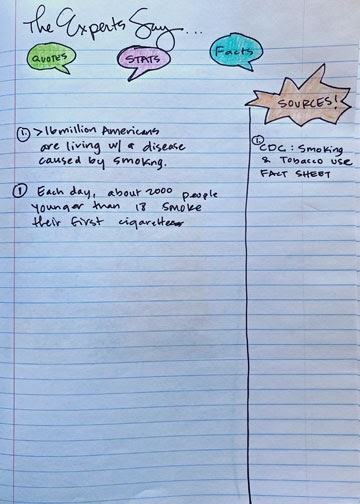

The Experts Say . . .

Facts matter in nonnarrative writing, and having a place to collect facts around an issue is important. There are different depths of research, and this page is where writers can “dip their toes” into the research pool.

Teach students to conduct light research and get a sense of what experts say about the topics. That’s what I did in the previous example about cigarette smoking. It took only a moment for me to learn the CDC statistic. Having a page dedicated to what “the experts say” will help guide the research process later, as well as help students begin to develop stronger support for their stance on different issues.

It is also a great way to see how students enter into the research process. Additionally, if a student is inspired to write about a personal issue, they can sometimes get stymied on finding research to support their stance. For example, if a student wants to write about wanting a gecko, they may not know how to angle their searches to find useful information. “The Experts Say” page is an excellent formative assessment to help guide upcoming lessons on the research process and using evidence to support your stance.

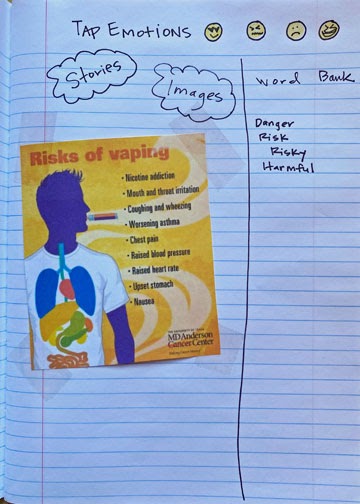

Tap Emotions

The Latin root for the word emotion means “to move,” because emotions often motivate what we do. Nonnarrative writing is more than facts. The savvy writer will also tap emotions. When readers feel excitement, humor, kindness, anger, or frustration, they tend to move to action. When students are collecting around an idea, they can create a “Tap Emotions” page. Encourage students to collect images and stories, as well as a word bank that will help them connect to readers by tapping emotions while they draft.

The writing notebook can be a tool to help students deepen their convictions, discover facts, and balance emotions in order to draft with confidence and meaning. These four pages will help students find their voices and learn to balance facts and emotions with the goal of changing hearts and minds with their words.