I would encourage anyone nearing testing season to read aloud Testing Miss Malarkey by Judy Finchler with colleagues. Simultaneous laughs and groans erupt at this portrayal of our society’s relationship with testing. The story of testing is told from the perspective of a student and begins, “Miss Malarkey is a good teacher. Usually she’s really nice. But a couple of weeks ago she started acting a little weird. She started talking about THE TEST: the Instructional Performance Through Understanding test. I think Miss Malarkey said it was called the ‘I.P.T.U.’ test.”

As the story continues, the kids are told the test “isn’t that important” and “won’t affect your report cards” or “mean extra homework.” But they watch the adults around them, and Miss Malarkey can’t stop biting her nails, and the principal loses it over No. 2 pencils with crumbly erasers. The parents attend a PTA meeting and fuss about test anxiety and real estate prices.

This story and the real stories it brings to life remind me that children listen wholly to our melody and only slightly attend to our words. In other words, they watch us to find out the true importance of THE TEST.

Teachers’ Approaches

A teacher’s approach to testing is as unique as his or her teaching style. I worked with two teachers who were disappointed in their state writing assessment results, and took very different approaches to dealing with those results.

When I asked Sharon how she taught writing last year, she showed her copied packets of short writing activities and daily journal prompts. I knew that Sharon was a feedback queen. She wrote questions and comments all over the students’ papers, and they corrected the papers and handed them back to her. She added, “We did several all-day writes to prepare for the test.”

Bill had a very different approach. He loosely used a writing workshop model and had his students giving each other peer feedback. The students were accustomed to writing projects that they collaborated on together. Most of the projects were self-assessed, and he expressed that they were anxious when test time came around.

When we sat down together, I asked, “What do kids need to do to be successful on the statewide writing test?” I took notes as they talked:

- Bill: They need to be able to generate their own topics.

- Sharon: They need to be able to follow the directions of the prompt.

- Bill: They have to care about what they are writing about.

- Sharon: They need to use good conventions.

- Bill: They need to be able to use that checklist to revise.

- Sharon: They need to organize and sequence their ideas.

- Both Bill and Sharon agreed: They need to elaborate.

We went through the list item by item, and I asked, “How can we teach kids to [generate topics, follow directions, care, use conventions, revise, organize and elaborate] independently by the spring?”

What Helps?

In the movie Apollo 13, an intense space capsule scene ends in disaster. Fortunately it turns out to be only a simulator in a virtual reality capsule that helps astronauts and the ground crew prepare for missions. Because astronauts typically have only one chance to complete a task in space, they need to be well practiced before the real thing. In fact, simulation mishaps give them a chance to avoid future disasters or aborted missions.

Although high-stakes testing is not the same as launching a space shuttle, participating in a well-planned simulation can help students prepare for the real thing.

It benefits test takers to know what their materials will look like, what the directions will sound like, and how to budget their time and develop stamina for the duration of the test. In our state, fourth graders have an entire day to prewrite, draft, revise, edit, and write a final draft on two separate testing days (one for narrative and one for expository writing). A couple of weeks before the test, many teachers stage an “all-day write” to help simulate the testing experience.

Guiding a Simulation

Working with Bill and Sharon, we planned for an all-day guided write with a continual workshop model flowing from minilesson to independent work time to reflection. Sharon anticipated that the long writing criteria checklist that was read to the students in the direction phase would be ignored because it was so wordy. During the simulation, we annotated and illustrated the checklist to translate it into words that the writers knew.

Then Bill suggested kids needed to know how to personally respond to the prompt. In response we taught a minilesson on how to bring your personal passion to a prompt. I began with an oral prompt. “If I love to play touch football” (and a number of the students at their school do), “what might I write about if the prompt is ‘tell a new student about what you like best about school’?” They all agreed I should write about touch football at recess. “If I love animals and the prompt is write about something to improve the school, what might I write?” The kids thought up how I could write about having animals in the classroom. “Because I’m an expert in touch football or know a lot about animals, I’ll be able to bring more to the prompt.”

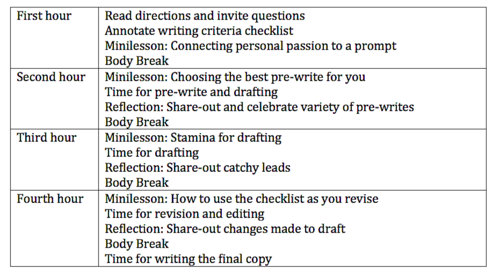

Here is an outline of how we paced our guided all-day write.

Reflections

Although we anticipated many of the obstacles in an all-day write, we were still surprised. Bill’s face drained of color when over half his class was unsure what was meant by the word plot in the narrative checklist.

I smiled at him. “There’s still time.” The next week we brought out the book The Plot Chickens by Mary Jane Auch to give kids a great reminder of plot and model what good writers do.

Four of Sharon’s students finished in the first hour. Three of them were capable but hurried writers who wrote less than a page. As I conferred with them, I said, “With such a short piece, you would be cheating yourself out of a stronger score.” All three went back, slowed down, and wrote more elaborated pieces.

Bill said, “After doing this I realized that my writers spent so much time cooperating that I hadn’t explicitly taught them what they needed to be able to do on their own. I think last year my kids panicked because the situation was so foreign to them and no one could help. Showing them how to transition to this is important.”

Sharon admitted, “Even though we did lots of practice writes, I’ve never done it so intentionally. I think this allowed them to walk through it and ask questions all day long. It surprised me how much fun it was, learning about the test day together.”

I don’t support teaching to the test and stressing kids out, but I do support timely teaching about the test in a relaxed manner. One of the last tasks I assign is this: Draw a picture of what you think the person scoring your work will look like. Often I get pictures of robots or squinty-eyed teachers with tightly bound hair. “Would it surprise you that people like me score those tests?” I ask. They gasp, “But you are nice!” “Yes,” I say, “and those people scoring, just like me, want you to do your best on THE TEST.”

Consider these questions:

- How do you relate to Bill and Sharon?

- What do your students need to be able to do independently for testing?

- What obstacles do you anticipate?

- What simulations might help them learn about the test so they can be successful?

- How do you differentiate between teaching to the test and teaching about the test?