In my classroom of gifted learners, I'm required to collect baseline data on my third- and fourth-grade students' reading abilities in order to set measurable learning goals for the year. Unlike most teachers, however, I'm faced with a dilemma to which few can relate: virtually all of my students have already exceeded the grade level standards in reading.

Why is this a problem? On its own, it's far from a problem; exceptional, motivated readers make for a uniquely challenging and fulfilling teaching assignment. But using quantifiable assessment for demonstrating growth is what keeps me at my desk long past the dismissal bell. My peers working with general and even special education students have a difficult, but much clearer mission: increase reading rate, accuracy, and comprehension to meet grade level standards. In today's data-driven education system, high performers' learning can be difficult to measure and hard data doesn't really tell their story.

Grading and reporting is trending toward a goal-setting model. For example, a second grader reading 75 words per minute in March may set a goal to reach 90 words per minute by June. This is a clear and concrete example of using data to make instructional decisions. But should a third grader reading 220 words per minute be encouraged or expected to read any faster? Should an eight-year-old with a sixth-grade reading level need to move to the seventh grade level in order to show meaningful growth? These are the questions I ask myself as I help my students set measurable goals.

A few years ago, I had a third-grade student who conquered any leveled reading inventory I slid across the table. I gave up after the seventh grade level because neither of us was learning anything from it. When I shared this with his parents, their reaction surprised me. "How can we slow him down? We've seen the books designed for readers that age and they're far too sophisticated. We don't want our eight-year-old reading about puberty and drug use." The position I found myself in was this: I was expected to move him from the seventh to the eighth grade reading level in order to demonstrate a year of growth during a year of school. My goal, data collection requirements notwithstanding, was to enrich, but not necessarily increase his present reading ability. Yet how could I measure this enrichment, must less report it?

Wider Readers

I recently gained some perspective on this issue during one of my only successful gardening experiences when I added coleus plants to my flower beds. For those who don't know, coleuses are vibrant pink and green-leaved plants that add striking beauty to an otherwise dull landscape. I nurtured them to encourage quick growth so they'd catch up to their botanical peers.

When stalks of flowers sprung from the middle and quickly doubled each plant's height, I couldn't resist the urge to brag to a friend. "You have to cut those flowers off," she said.

Cut them off? What could be more counterintuitive than inhibiting this obvious measure of success?

"They'll become more full and sprout new leaf growth if you do," she went on. "Otherwise, they'll be too tall and thin and may even topple over. Height isn't what you're aiming for with this plant."

As I begrudgingly trimmed the flower stalks, I realized that my students are not unlike coleus plants. They can show impressive growth in a short amount of time. After all, they read fast. They retell accurately. They answer questions correctly. And they get better at it all the time. But continuing to measure and teach to these expectations alone only makes the students "taller" readers. I want them think more deeply, make connections to content area learning, apply reading skills to research projects, and expand knowledge by exploring various genres. I want them to be "wider" readers and grow new leaves.

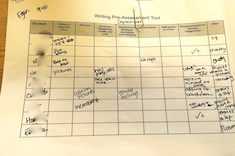

Alternative Assessments

An example of a fluency performance task I've used is reading aloud. I ask students to practice a poem or favorite excerpt from a book to share with the class. Using a rubric to score the presentation, I evaluate expression that matches the content or author's voice rather than the student's rate or even accuracy. And as an alternative to traditional comprehension assessment, I use clear criteria to track and measure the quality of student responses in book club or shared inquiry discussions. I look for active listening, complexity of ideas, and contributions that build on the ideas of others.

Any checklist of indicators of gifted children includes points like advanced vocabulary, large storehouse of information and elaborate thinking. But if a gifted child can't share that thinking with others, there's no expansion. These students are our future politicians, professionals and creative problem-solvers; they need to have strong communication skills so they can get their ideas across to an audience. Students self-assessing their own speaking and listening can be part of evaluation. When they internalize specific criteria, they can raise the ceiling of expectations for themselves. While reading aloud, tracking student listening and responses and using students' self-evaluation information aren't the only assessments I use, they demonstrate alternative ways to measure fluency and comprehension in a way that challenges the highly capable learner.

There is much work to be done in meaningful assessment of our gifted readers. They deserve the chance to demonstrate growth and achievement in ways that match their learning needs. We need to expand our assessment practices and beliefs about growth indicators. Not all gifted readers are in specialized programs, so exploration of this topic potentially benefits all reading teachers. In fact, the outcomes may extend beyond the gifted classroom and have indications for general education as we consider more purposeful measurement of success. Our advanced readers may not be meeting their own potential even when their performance far outweighs peers. Rigorous and comprehensive assessment is necessary to challenge both students and teachers to meet high expectations. Help us grow, too.