Using mentor texts is one of our favorite things to do with our students in writing workshop, because it pushes them to try things in their writing they wouldn’t have otherwise. Using mentors closely is new to most of our fourth graders in the fall, but it’s exciting to see their ability to talk about a writer’s work and then try to do the same kind of work in their own writing grow across the year.

We also teach our students that any text (published or a classmate’s) could be a mentor for our writing. Usually, the mentors we use in our classroom are the same genre in which we’re currently writing, but we know that there are always things to be learned from and used across genres in powerful ways.

When we give our students a mentor text to support their writing, they’ve always heard it at least once, just as a reader and for enjoyment. It’s almost always a text we’ve read aloud to them at some point so that they’re all able to access it. That way, they’re already familiar with what’s in the text and can move beyond what it’s about to focus on the writing work being used.

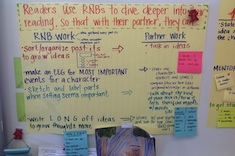

Although students often have their own copies of mentor texts so that they can work with the texts next to them, we also use mentor texts on our writing charts. Below we share some of the ways in which we’ve used charts to support students in using mentor texts in their writing.

Highlight Powerful Language

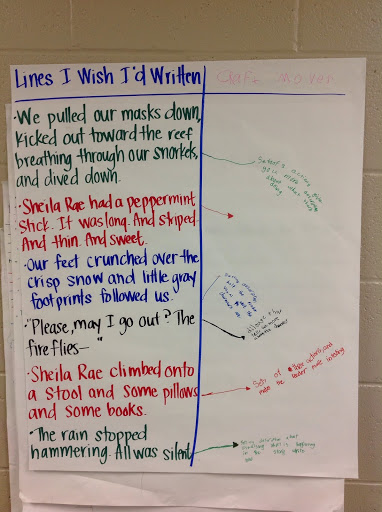

In small groups, our students reread mentor texts together and mine them for golden lines, or lines they wish they’d written. They’ll write these lines on a two-column chart like the ones below. We decide as a class which colors we’ll use for each text so that we’re all able to easily identify the texts from which the lines came.

Once students have identified beautiful lines and language, they work to fill in the right side of the chart, where they name the writing work happening in those lines in a transferable way. We’ll model this with the sentence “The trees stood still as giant statues” from Owl Moon by Jane Yolen. We can’t write down that the writing work this author did was to describe the trees, we’ll say, because that doesn’t help me if there aren’t trees in my story. So I need to push myself and answer the question, “What is the work this writer did that the writer of any story could do?” We’ll give students a chance to talk to their partner and help nudge them toward some more universal language, writing something like “Writer compares two things in a surprising way (a simile!)” on our class chart.

The whole class used the same color-coding system so that anyone using the chart would know which mentor text the golden line came from. Sometimes, instead of giving all the texts to each group, we give each group a different text. In that case, their chart is not a collection of golden lines across the texts but of golden lines from a single text.

These charts become tools students can use as they’re writing, and the fact that they made the charts themselves in small groups gives them ownership of the work and makes it more likely that they’ll refer to it as a resource as they work.

How Mentor Texts Influence Our Writing

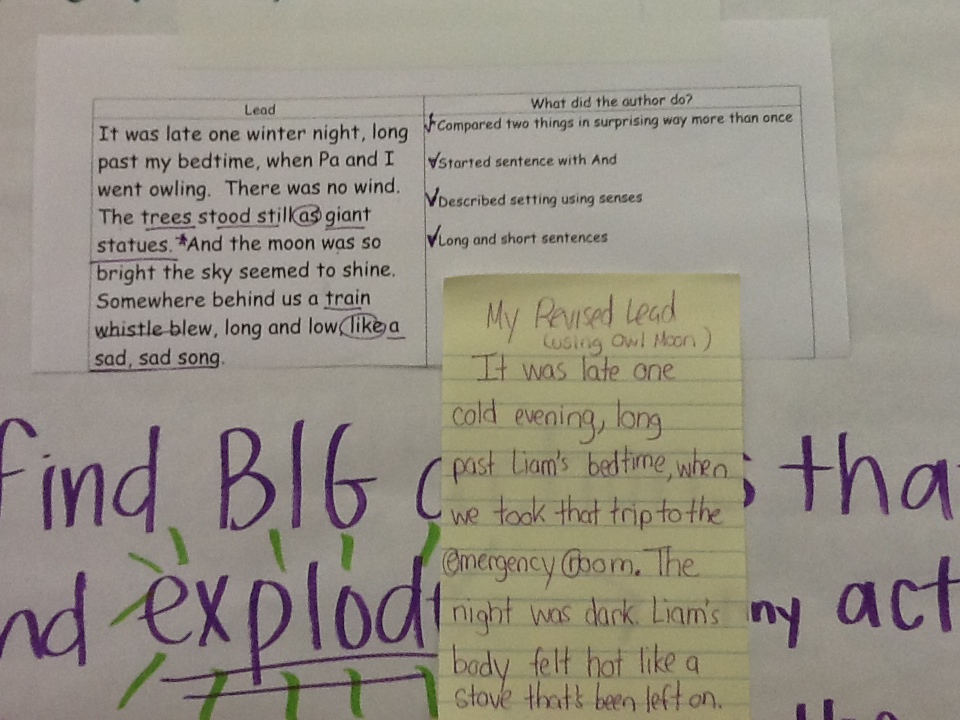

A chart similar to the T-chart above has a longer part of a text, like the beginning or ending, on one side and the writing work being done in that part on the other. In the chart below, students were given part of a chart with mentor leads on one side and space to name the writing work on the other side.

This chart models for students how we can read a lead, name the writing work the author did in that lead, and then mimic it in our own writing, either as part of our first draft or during revision. In the example above, we read aloud and annotated the lead from Owl Moon and then wrote a lead that used similar craft moves for our own personal narrative story. We use sticky notes and removable sticky tape on the chart so that everything can be removed and borrowed at students’ seats as they work.

Annotated Mentor Texts

We encourage our students not to think of their first draft as a “sloppy copy,” but instead to always do the very best work they can, even though that means they’ll know more later and be able to make that draft even better. Our goal is to write our best first draft. Mentors are helpful in doing this, because we use mentors to give students things to consider and try as they’re writing their first draft. Some students have found a lot of success in writing their first draft alongside a mentor text.

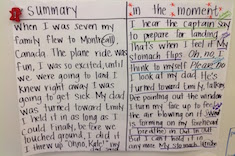

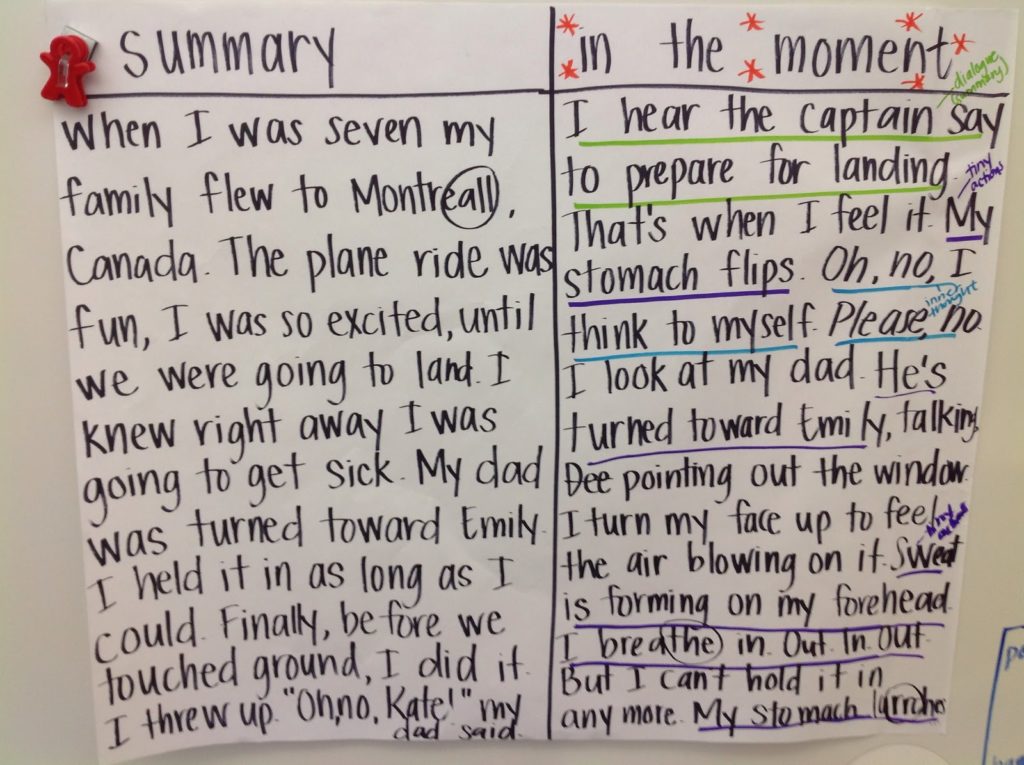

A big focus during our first unit of study, personal narrative, is writing in the moment rather than summarizing what happened. To support students in this, we have the chart below showing the same scene written as a summary and written in the moment. The in-the-moment side has some annotating to name the writing work that helped us write more in the moment—things like tiny actions, dialogue, inner thought, and setting description. We encourage students to refer to it as they’re drafting, and also print individual copies for some students so that they can draft alongside the annotated mentor.

Students can also refer to this chart as they’re revising. Some have enjoyed highlighting the different types of details in their draft using the mentor chart as a guide for the type of details they might look for in their writing. For example, they might highlight all of their tiny actions in pink and the inner thoughts in blue. The highlighting shows them what they might have used too much of or what they might be missing, and helps them plan for revision.

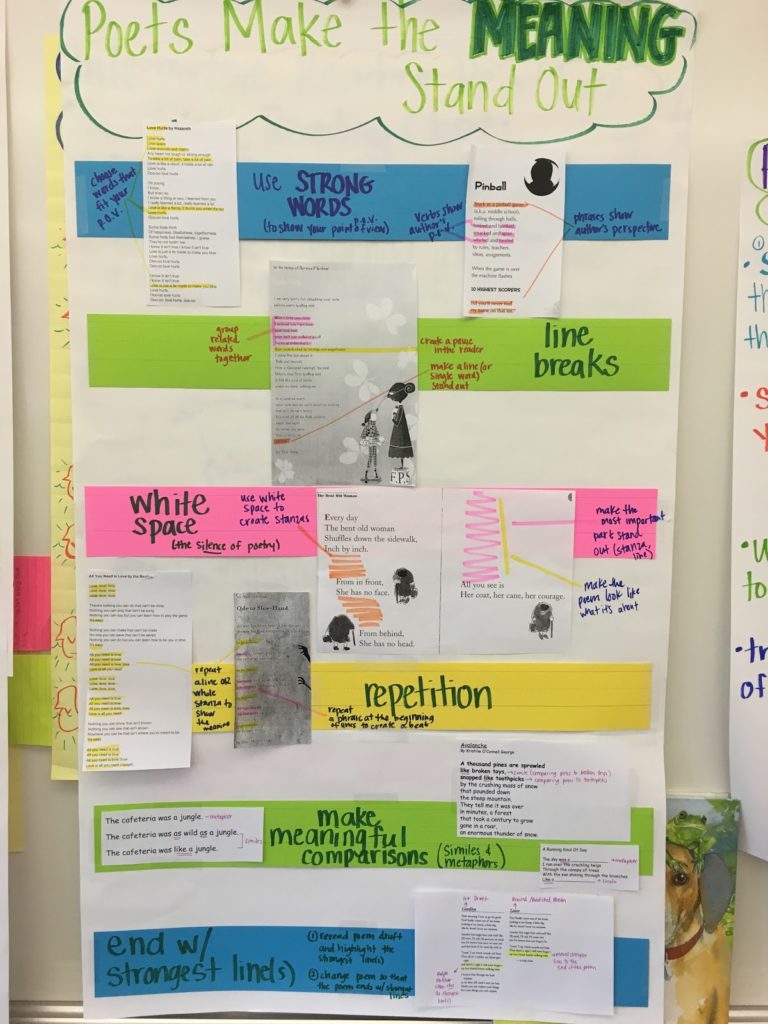

Similarly, on the days during our poetry unit of study that our students are drafting poems, our minilessons will focus on studying mentor poems to find ways that the poets make the meaning of their poems stand out. On the chart below, we display the different moves of the poets alongside the mentor poem. The parts of the poem are highlighted and annotated to show an example of the writing work.

Students are able to use the chart as they draft their poems so that their first drafts reflect some of this work. We keep the chart at the front of the room during this unit of study so students can walk up to it or look at it from their seats. They can also access a digital copy of the chart on our class set of iPads so that they can look more closely at the mentor examples and annotations as they draft. Having access to the charts on iPads always seems to increase our fourth graders’ usage of the charts as a resource in their writing. There’s something appealing about getting to zoom in on the photos and have them there at their seat so they can go back and forth between their poems and the mentors on the charts as they draft, and using the mentors in this way leads to more thoughtful and purposeful writing.

Collect and Display Students’ Inquiries

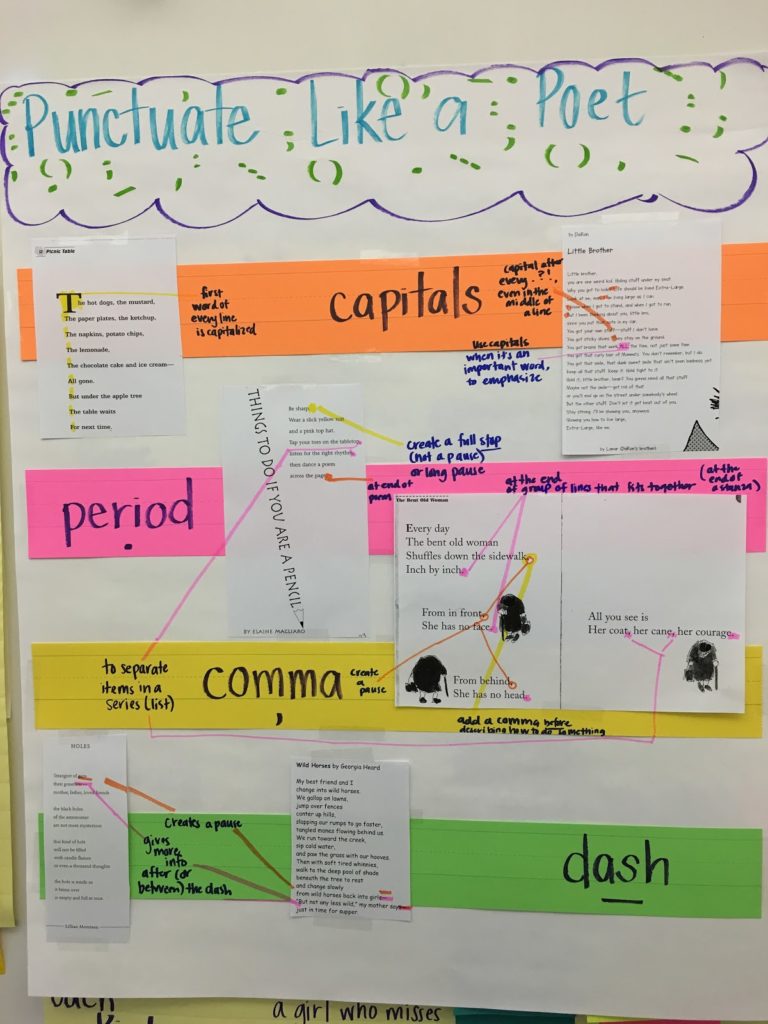

Charts are a perfect way to make a class display of student inquiries of mentor texts. During our poetry unit, for example, small groups or partnerships study one or two punctuation marks in mentor texts. (The punctuation marks and mentor texts have been preselected for students so that we’re sure the mentors have the punctuation they’re studying.) They identify different ways the punctuation marks are used and then report to us and share their findings with the class. As they share, we highlight examples of the punctuation marks on our class chart, below, and annotate the highlighted examples with the description of how the punctuation mark was used. In this way, the chart becomes a collection of the work of the entire class and allows everyone to benefit from everyone else’s inquiries.

Charts and mentor texts separately are powerful yet often underused tools in writing workshop. Both charts and mentors have the tendency to be introduced or referred to, but then fall away without much influence over students’ writing, especially as they’re writing independently. Linking mentor texts and charts in these ways helps to make them both used a lot more; they become accessible tools to students that can be referred to again and again during their independent writing time.