As we work with primary-grade teachers during reading workshop, many of them ask us how to challenge the advanced readers in their classrooms. These young students learn to read quickly and quite naturally—in fact, many were reading before they entered kindergarten. Teachers sometimes find themselves struggling to challenge these students in a developmentally appropriate manner. How do we facilitate these students’ continued development as readers while concurrently allowing them to embrace the joys of being five- and six-year-olds?

When precocious students read aloud, it can sound effortless, as if the words simply lift off the page. When we ask these students what books they are reading, we often hear about chapter books that were written for third-, fourth-, and fifth-grade students. These books, although engaging, may be difficult for younger students to fully grasp because of sophisticated themes, characters who are at a different stage of life, and unfamiliar settings or time periods. For example, many advanced five-to-seven-year-olds find their way to the Magic Tree House series. Although these stories are full of exciting time-travel adventures, the themes and stories relate to historical events for which these young minds may lack background knowledge.

When we confer with these advanced kindergarten and first-grade students who are reading sophisticated chapter books, many are getting only “the gist” of these difficult texts. When children repeatedly read text that they can’t fully understand, they are learning that not all parts of a book have to make sense. We don’t want children to learn that simply skipping over sections of the story that don’t make sense is a strategy proficient readers use. As with all readers, we want them to construct meaning as they read and know that, above all, the text must make sense.

How can teachers navigate between challenging these students and using developmentally appropriate practices? Here are some questions that we have been thinking about around this topic:

- Why should we challenge these young readers?

- What are some ways to challenge young readers without increasing text level?

- How do we talk to parents about what it means to be “challenged” in reading?

- What are some developmentally appropriate books?

Why Should We Challenge These Young Readers?

When we think about our hopes for advanced readers, the concept of self-efficacy comes to mind. We want all children to know what it means to learn something. We want them to have the experience of working hard and seeing the rewards. In all grades, but especially in the primary grades, we want children to learn that the effort they put into work and play makes a difference—you are proficient at something because you spend lots of time trying something, at times failing, and then practicing to improve. As Ellen Usher and Frank Pajares (2008) write, “Although failure may occur periodically, when students notice a gradual improvement in skills over time, they typically experience a boost in their self-efficacy. Mastery experiences prove particularly powerful when individuals overcome obstacles or succeed on challenging tasks.”

These readers, however, didn’t work to become proficient. In many instances, the skills were acquired quite naturally; therefore, providing them with opportunities for developing self-efficacy is even more important. But challenging our young advanced readers does not need to be only about reading harder books. These young minds have lots to learn about thinking deeply when reading, and some of the best materials for teaching deep thinking are short picture and chapter books.

What Are Some Ways to Challenge Young Readers Without Increasing Text Level?

When we think about challenging these students to think deeply when reading, we often think about how to broaden their thinking rather than increasing text level.

Reading Several Books by One Author

Reading several books by one author is one way to lift the students’ understanding of how to build background knowledge, identify author’s craft, and analyze literary elements when between and within texts.

We often begin this type of work by having a student choose two short texts by the same author. Jan Brett, Kevin Henkes, Ezra Jack Keats, Angela Johnson, Tomie dePaola, Gail Gibbons, Pat Hutchins, Leo Lionni, Mem Fox, Robert Munsch, and Lois Ehlert are all wonderful choices. Many of these students do not know these authors because they jumped right into long chapter books.

Once the children have two books to read, we ask them to draw and write about what they notice. How are the books the same and how are they different? Analyzing the students’ work helps us know what the children already understand and what concepts around genre, author, and/or literary elements are unfamiliar.

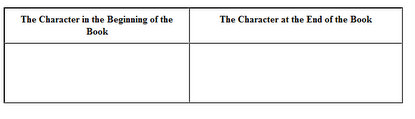

Using this assessment data we then begin a discussion around the literary elements of character, setting, problem, solution, and theme with students. With some students we begin by talking about the characters. To advance their ideas around characters, we teach them that some characters in books change and some do not. (We often have to explain to more literal learners that changing doesn’t only mean that the character changes his or her clothes; it can also mean that they make different decisions, get new ideas, or learn something new.)

After modeling in a small group, we ask the children to reread their stories and look for which character is changing in their books. Young kids can express this sophisticated learning in developmentally appropriate ways by drawing their responses and adding speech bubbles to their illustrations. Peter’s Chair by Ezra Jack Keats is one wonderful example for teaching students about how characters change.

With other students the assessment data takes us into comparing the plots of the different stories. For example, if children read The Mitten and The Hat

by Jan Brett, we model how to find the problem in the text. We then have the children reread their books and determine the problems in the story. Inevitably they return with lots of problems in each story. We can then stretch their learning by helping them identify the main problem. Once they have worked through this book, they are ready to read a third book by the same author to see if this author uses the same main problem in all of their stories or have the characters face a different problem.

These types of lessons can be used to teach children about each literary element. The goal of these lessons is to broaden students’ thinking about the books they are reading and to use writing and drawing to show their sophisticated thoughts. We are hopeful that as these readers get older and move into longer, more sophisticated texts, they can use this knowledge to help them identify and analyze the mood, theme, and characters in the texts they are reading.

Reading New Genres

Many young advanced readers thoroughly enjoy reading a particular type of book and have not yet experimented with reading a wide variety of genres. Some of these children can’t get enough nonfiction, whereas others are avid fantasy readers. We can challenge these readers by exposing them to new genres and teaching them how to read these genres.

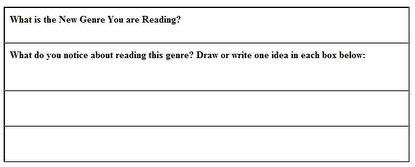

We begin lessons about genre by having students read two very simple texts in a new genre and then having them draw and write about what they notice. “What do you notice about this new genre? How are these books the same? How are they different?”

Once we know what the student recognizes about this new genre, we can build our teaching from our assessment data. For example, one student reading two different nonfiction books by Gail Gibbons notices that many of the pictures are labeled and that the book is teaching the reader information. With this data, we now teach the student how to use the different text characteristics of nonfiction (e.g., bold print, headings, charts, pictures, and so on) and how nonfiction text is organized. Young students can learn about different text structures such as chronological order, topic/details, and question/answer formats. Students can read several nonfiction texts on one topic and then write and draw about the organization of the book as well as identify the new concepts they are learning.

Teaching Phonics

Since many advanced readers read fluently, the need to develop their phonetic skills may be overlooked. When analyzing data patterns of advanced kindergarten and first-grade students entering grades 3–5, we have found that some students’ reading skills plateau in the upper intermediate grades. These young students often have very strong sight-word memories but have not fully grasped underlying phonetic concepts. In kindergarten and grade 1, these students have no use for phonetic concepts, because they can already read all of the words that the teacher is using to teach the phonics lesson. However, when they are in later grades, words such as emancipation, Mt. Vesuvius, or instigate can pose challenges, because the words in the text are not part of their sight-word inventory. These readers never acquired the underlying phonetic knowledge when they were younger, and therefore struggle when decoding unfamiliar multisyllabic words once they hit grades 3–5.

In kindergarten and first-grade classrooms, we can support these students in acquiring phonetic skills by first assessing their knowledge of phonics. We recommend that students’ phonetic skills be assessed using a phonetic test with nonsense words and by analyzing a student’s writing. The Names Assessment by Patricia Cunningham and Lexia’s QRT are both quick diagnostic tools that give teachers information about students’ skills in phonics.

Once we have identified the phonics skills necessary to support these readers, we can teach these students the underlying phonetic concepts during independent and small-group reading and writing sessions. During these sessions we explain to the student why they are learning this concept and how it will help them decode unfamiliar words. We often show them a difficult word and talk about how this concept will help them with spelling and reading unfamiliar multisyllabic words. When we take time to explain to these students why they are learning this phonetic concept and how it looks in harder words, they often are much more attentive and stop viewing phonics instruction as something that is too easy for them.