I’ve been working with a team of intermediate teachers to develop a plan for teaching conventions. It’s a small but diverse group, and we’ve already worked together to find time in our schedules for convention instruction and determined what conventions we want to teach. At the end of our last meeting, Greta looked at the list of conventions we came up with and thought about integrating this instruction into writing workshop. “It’s a bit of a contradiction, isn’t it?” She chuckled. “We’re simultaneously inviting inquiry while being explicit about the conventions and rules. It’s like we’re saying we need to get students asking questions, and at the same time we need to tell them what is what.”

I thought about Greta’s contradiction as I drove home listening to the radio. The song “What Is Love?” by Haddaway came on from the movie Night At the Roxbury. You know it, right? “What is love? Baby don’t hurt me. Don’t hurt me. No more.” That’s pretty much the whole song. I always think of Will Ferrell and Chris Kattan and their Saturday Night Live skits where they headbop to the beat. And that’s the inquiry of the song: What is love?

Other artists took a different approach to the topic, like the ballad “Love Is” by Vanessa Williams and Brian McKnight. “Love breaks your heart. Love takes no less than everything.” They are telling. They are being explicit: love is this.

But Foreigner brings it all together with “I Want to Know What Love Is.” They sing simply, “I want you to show me.” That’s how I get to my own understanding that teaching conventions with an inquiry stance is knowing when to allow for discovery and when to be explicit. Inquiry and explicitness are not contradictions; one enhances the other.

Dolphin Song

As part of our commitment to each other, we each brought two pieces of student work. Both of my samples came from an informal class book written by fourth graders of mine a few years ago. I copied and brought the first paragraph of each student’s work.

I started us off these guidelines: “When we look at these samples, let’s start by noticing the evidence of the conventions the writers know and use. Then when we look at errors let’s talk about the patterns of errors with these three questions in mind:

Severity: Do the errors impede making meaning?

Variety: Is the variety of errors small or large?

Density: How often do we encounter errors as we read?”

Dolphin Song

Once a dalphin in named angel did’nt hav a choice. She wanted a voice badly. the oter dolphins maed fun of her. One knight while splashed and jumped. while she did that she was wishing on the north star.

Meg, Kenneth, and Greta leaned forward as we listed what the writer of “Dolphin Song” was doing well:

- The writer knows how to compose sentences. Most of them have one idea.

- Her subjects and verbs agree.

- She knows to capitalize at the beginning of some of the sentences.

Meg said shyly, “At first I thought: there isn’t anything going well, this is a mess! But now I can see after being in school five years this writer knows a lot.”

I shared one of the quotes I’d marked about errors, from Janet Angelillo in her book A Fresh Approach to Teaching Punctuation: “What may appear to be an error is often a milestone on the way toward a new skill or evidence of lack of experience—experience that we, as teachers, can provide young writers.”

Meg summarized, “So maybe this writer needs time and encouragement with capitalizing at the beginning of the sentences and she’s almost there.” We nodded.

“And what about density?” I asked as we looked back at the piece.

“These errors are pretty dense,” Kenneth said and I nodded. “There’s several per line.”

“And variety?”

Greta responded, “I see problems with spelling, contractions, high frequency words, sentence construction, capitalization, homophones . . . That’s varied!”

“What about severity then?”

Here the group didn’t agree. Meg and Greta said they were severe, but Kenneth made the point that we’d all been able to read it. It wasn’t crucial for us to see things the same way because we all agreed the writer of “Dolphin Song” would benefit from convention instruction.

“What would happen if we tried to attack all of those with this writer?” I posed.

“She or he would feel completely defeated. Overwhelmed. Like nothing was going right,” Kenneth offered.

We transitioned to my next writer, who was more in control of his conventions.

How Owls Got Wise

In the beginning owls were stupid. At school owls were lucky just to get by with a “C” on a test they were called names. They didn’t like that so. They decided to study many different subjects at night. In fact, they got so smart that they were the WISEST now if you want to learn something you need to talk to your local owl.

Again we listed what the writer was doing well:

- The writer is capitalizing.

- He is experimenting with quotations.

- He knows how to punctuate contractions.

- His spelling is conventional.

There wasn’t severity, density, or variety of errors in this piece, but there was something consistent. There was an example of a fragment: “They didn’t like that so,” and two run-together sentences: “At school owls were lucky just to get by with a ‘C’ on a test they were called names” and “In fact, they got so smart that they were the WISEST now if you want to learn something you need to talk to your local owl.”

Kenneth was surprised by the term run-together sentence. “I thought it was a run-on.”

I nodded. “I think the only difference is that a run-on sentence might even be more than two sentences as it goes on and on and on. The run-together sentences are two sentences fused without any punctuation.”

Greta said, “That is a trend with my two writing samples but also many of my other writers. I see fragments that aren’t purposeful fragments and I see run-together sentences.” Kenneth and Meg agreed.

“So those are the sorts of things we want to note for whole-group lessons as trends. Let’s write down fragments and run-together sentences.”

Prioritizing for Instruction

By the time we were finished we had a list:

Homophones (especially: to, too, two, its, it’s)

Fragments (not purposeful)

Run-together sentences

Punctuating dialogue

Proper nouns not capitalized

Shifting verb tenses

“When you look at our list, are there some conventions that get more in the way than others?”

Meg said that run-together sentences were a bigger deal than punctuating dialogue. Kenneth added that shifting verb tenses forced him to go back and reread more than once while homophones were less confusing. They reordered the list with the most pressing conventions at the top.

“Since we are planning for next week, let’s pick our top one: run-together sentences. Even though we haven’t combed through the Common Core State Standards. I know it’s there.” I skimmed my finger down the page. “Yep, produce complete sentences, recognizing and correcting inappropriate fragments and run-ons.”

“So, students need to recognize and correct run-togethers to produce complete sentences. How do we do that?” Meg asked.

“Well, we start with a model, right? We pull some correct sentences, probably sentences they love from picture books or our read aloud and we post those.” Greta said.

“Then?” I asked.

“We would note that complete sentences have a whole idea. They usually have a subject and action,” Kenneth said.

“And they sound right,” Meg added.

I showed the team how to use questions to help students test run-togethers as they develop their ear to determine if it “sounds right.”

Take the Wise Owl writer’s sentence: In the beginning owls were stupid.

We could ask and answer the question, “In the beginning were owls stupid?”

But now take the run-on sentence: At school owls were lucky just to get by with a “C” on a test they were called names.

There are two questions: At school were the owls lucky just to get by with a C on a test? and Were they called names?

As with many tools, there are times the question test won’t be as helpful. When writers get more sophisticated and build increasingly complex sentences, the tool will lose its effectiveness. Then again, hopefully at that point they won’t need it.

“So that’s the inquiry part!” Greta said. “Now they go back and question themselves as writers.”

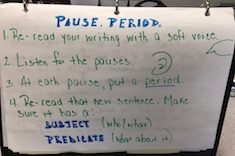

Our time was up, but the team had a plan together to teach run-together sentences that week. Tuesday they would model correct sentences and note the three components of: a whole idea, a “who” and a “what’s happening,” and sounding right. Greta planned to use the words subject and predicate alongside the more kid-friendly language. Kenneth and Meg agreed. Wednesday they’d show run-together sentences and have the students discuss why they weren’t complete sentences. Thursday they’d share the questioning strategy, and have the students look back at an older piece of their own writing to test their sentences.

At our next meeting we agreed I’d bring back the list of the worrisome conventions and see what else was in the Common Core Standards. We’d also talk more about conferring with individual writers that had severity, density and variety of errors.