Marie Clay reminds us, “The one closest to the classroom experience is in a unique position to see and communicate a reliable and valid instructional perspective of the child.” In data meetings and professional learning communities, we sometimes become concerned that conference notes and teacher observations are not being viewed as valid assessments. We are hearing that only “universal screeners” count in the world of response to intervention.

We had the privilege of hearing Tony Wagner and Michael Fullan speak at the National Staff Development Council conference in St. Louis. Their message came through loud and clear: We need to balance our assessments to truly inform our practice and understand the learners in our schools. We need to respect and honor the observations, notes, and day-to-day assessments teachers create and use in their classrooms every day in addition to the external measures required by district, state, and federal mandates. Tony Wagner referred to the use of universal screeners in isolation as “accountability on the cheap!” Hearing these two experts and many other excellent presenters at NSDC reinforced the importance of staying the course and continuing to encourage schools to balance their assessment plans.

One way that we have been trying to validate teachers’ day-to-day assessments is by supporting them in analyzing and using their conferring notes. Triangulating data from multiple sources when making instructional decisions is essential. Teachers always bring their conferring notebooks to the data meetings we facilitate, but we often don’t use them as effectively as we could because the process seems too daunting. We asked ourselves, How can we better use conferring notes to make instructional decisions easier? Here are a few ideas that have worked for us.

Analyze as You Go

Taking the time to go through all of your notes on a nightly or weekly basis outside the school day can be too time consuming. Some of us would rather go for a run, bake cookies, or do almost anything else than spend our evenings looking through a huge stack of classroom notes. We have been trying a new system to help us record the patterns we are noticing in our small groups and individual conferences at the same time we are recording our conferring notes.

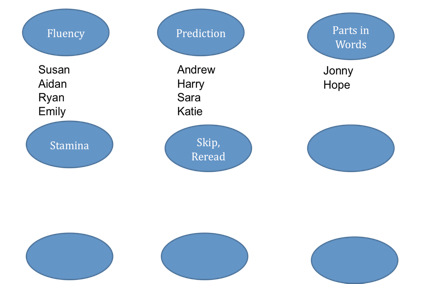

This form (or something like it) is kept in the teacher’s conferring notebook or clipboard. As a new concept or strategy emerges, we write the concept or strategy in one of the circles. We then list students who need to develop that strategy under the circles. This allows us to reflect on the needs of the students in our classroom. If we find we cannot fit all the names under the circle, then we may think about teaching that concept or strategy in a whole-class lesson or providing further scaffolding in small-group lessons. If we find that some students are listed under several circles, we are then pushed to think through our priorities for each child. We can make a plan for the next week or two and then reassess next steps for each student. Taking the time to write down the patterns we are noticing as we are working with students helps us use our observations to inform instructional decisions.

Protocol for Analyzing Conferring Notes in Staff or Team Meetings

Using a protocol to analyze conferring notes allows us to reflect on student work from the past month and use this information to plan the next month’s instructional priorities. While we are constantly monitoring students’ daily progress, it is also important to take the time to reflect monthly on what we set out to accomplish. This reflection helps us determine if our students have made progress on our instructional priorities, and to set the next month’s priorities.

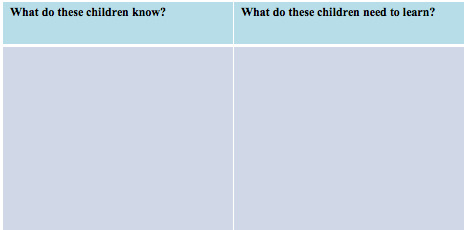

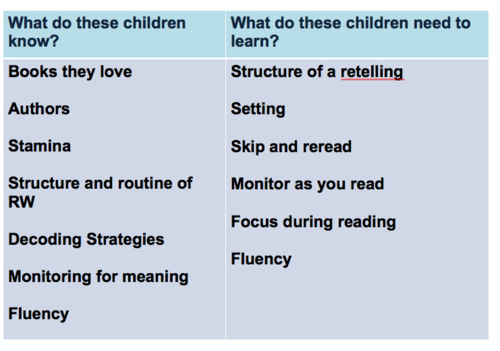

1. The first step of the protocol has teachers document what the students know as a result of the instruction provided in the previous month. This provides a snapshot of what children mastered, so that it is easier to determine an entry point for what they need to learn next.

2. The next step of the protocol has teachers look through conference notes to document what students need to learn. They typically use the goals section of their conference notes, any notes from small-group planning forms, and the key concepts for their upcoming unit of study or curriculum unit to choose these goals. Teachers write the goals in one column, and then every time they see another student who needs to achieve the same goal, they place a check mark next to the goal. Once they have finished analyzing each student, the chart becomes a frequency distribution graph of class needs.

If a goal has many check marks, a teacher can determine that it needs to be taught as a whole-class lesson. If there are only a few check marks, then this goal may be better suited for a small-group lesson. Once teachers have mapped this information on the form, they can plan the next month by choosing three to four key concepts to teach to the whole class, in small groups, and to individual students.

3. The final step of the protocol is to fill out a monthly planning sheet to organize instructional time and decide how you will assess progress in the next month. Each teacher shares his or her action plan for the next month with the team, and we all think about how they can collaborate on their action plans.

Less Can Be More with Conferring Notes

Taking conferring notes is a little like cooking a holiday meal for the first time. You do not know exactly what you will need, how much you will need, and what you will ultimately really use. We tended to over-plan, over-buy, and over-provide when we first hosted the holidays. Now that we have done it a few times, we can pull it off and not have to eat leftovers for two weeks. When we first began taking conferring notes, it was the same issue—we tried to write everything down because we did not know what we would need or how we would use the notes.

We try to help teachers get more efficient at taking notes, so they can spend less time both taking them and analyzing them. We have teachers discuss in data meetings the type of information they find most useful in conferring notes, and how to organize their notes so that they can find this information quickly and easily. We then have teachers try to focus their documentation on certain types of information for the next month in their notes (for example, date, text title, strategy student is using, goal). Then they reflect again at the end of the month on how they would revise their notetaking. The types of information a teacher chooses to record often changes with the unit of study and with time. What is important to document in September will not be the same as what is needed in February.

Teachers also share some shorthand tricks they use to decrease their notetaking time. Some teachers write in different colors for different purposes (for example, goals are always in blue ink). Others have a separate column for goals so they can quickly determine the instructional priorities for their class. Clare tends to circle things she needs to do in her notes, put a square around goals, and put triangles around items that need follow-up. You’ll find your own favorite notetaking shortcuts as you use your notes to inform instruction.

In this era of accountability and assessment, we need to advocate for the teacher’s voice. Teachers know how students perform authentically in the classroom every day, and this information needs to be at the forefront of our instructional decisions. Conferring notes, anecdotal notes, and observations are at the heart of our conversations linking data and instruction.