“I’m finished,” Hayden says, waving his arm, clearly proud of his accomplishment.

We smile and let Hayden and our other “finished” students place their writing in the basket before we gather everyone for a few minutes before the period ends.

Our class has just finished a period of flash drafting. For those not familiar with flash drafts, this is when we use our plans, anchor charts, storytelling practice, and all the other nurturing work we’ve done to write our first draft in a fast and furious way. After a period of flash drafting every student has something written and is ready to begin, arguably, the most important part of the writing process: revision.

“A lot of us are feeling finished. We’ve written for 45 minutes straight and feel like we’ve gotten everything out that we have to say. It’s good to let your writing breathe, but we’re not finished. Tomorrow, we’ll begin revising. We know that’s where the real writing work gets done.”

A few students nod, while others look a little skeptical. Although most of these sixth-grade students aren’t new to workshop or the concept of revision, these memoirs are the first writing pieces that we’re taking through the writing process this year. From experience, we know that most of our students will need some encouragement to embrace the types of large-scale revision that we’ll be teaching.

Since the meaning of revision is to see again, we let the writing breathe till the next day. Then we get right down to revision, using the best teachers we know: other writers.

Revising with Mentor Text Excerpts

As writers ourselves, we know it’s powerful to see a model of the kind of writing we aspire to. Studying published writing that we admire gives us a clear picture of what our own writing can become, a road map guiding us in our own writing. It’s so much easier to write well when we’re shown what good writing looks like instead of told. So, our favorite tool for supporting student writing is turning to the texts that we have come to love as readers, mentor texts that can show our students great writing.

For this work, we turn to texts that we are familiar with: the texts that we’ve already read and know well. In our reading unit, we read a series of short memoirs with a goal of developing character theories. Now, we use these same memoirs by authors such as Adam Bagdasarian and James Howe to study writing.

Scaffolding Revision Work

When we read a great piece of writing, we can easily recognize it as great writing. The harder part is recognizing what makes it great. So, we begin the work of using mentors with scaffolds that support our students in using a mentor text. In our most recent lesson, we used a mentor text to teach students how to write with details to show how they’re feeling in their memoirs.

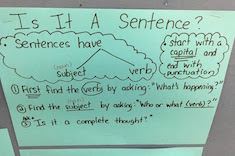

Step 1. Use a short excerpt of familiar text and notice what the author is doing.

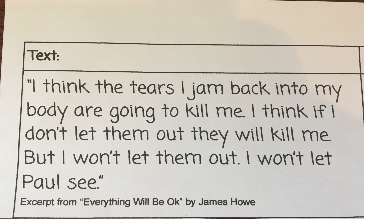

To start this lesson we show a short excerpt of text from “Everything Will Be Okay” by James Howe, one of the short stories we’ve been reading in our unit on developing strong character theories. Focusing on a short excerpt makes this strategy accessible to all of our students. We’ve chosen an excerpt where the author has done a good job of showing character feelings, since we’ve pinpointed this as writing work that can support our student writing by looking at their flash drafts.

“Today we’re going to reread a short excerpt from ‘Everything Will Be Okay,’ but we’re going to reread it with a writer’s lens. When we have our writer’s lens on, we read with the knowledge that every detail that an author includes is there for a specific reason. We chose this excerpt because we noticed that James Howe did something in this part that we could try in our own writing.”

At this point, we’ll read the excerpt aloud before pausing to think aloud.

“Hmm . . . When we reread this, we kept in mind what we know: authors have a reason for every detail they include. We thought about why James Howe included this part and noticed that after reading it, we know how the character is feeling. We can tell he’s really upset—distraught, even. But James Howe doesn’t name the feeling. We figure it out with the details. Like he doesn’t write, ‘I was so upset, and a little embarrassed.’ He shows us, in a much more sophisticated way.”

Step 2. Name what the author did.

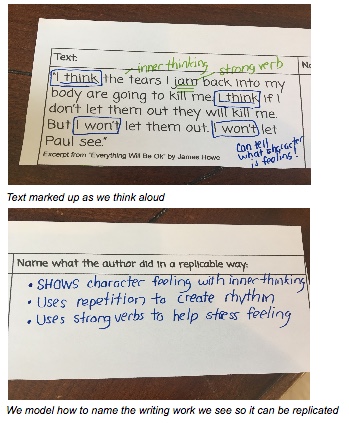

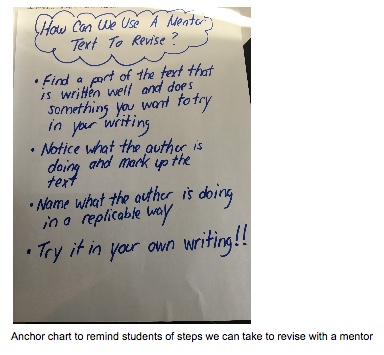

Once we’ve thought aloud about what we’ve noticed, we mark up the text and give a name to what we notice so it can be replicated in any piece of writing.

“So, James Howe writes in a way that shows how the characters are feeling without just saying a feeling word. The next step for us is to name what he did so we can try that in our own writing. We can look closely at the details he used and name them. I notice here that he says, ‘I think…’ James Howe is using inner thinking to show how he’s feeling. I also notice here that he wrote two sentences of inner thinking in a row that started the same: ‘I think… I think…’ And he used repetition again when he wrote, ‘I won’t…’ I like the rhythm that creates. That’s something I could try in my writing.”

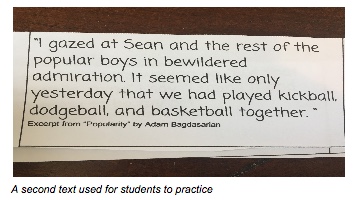

Step 3. Before trying them in our own writing, we practice the first two steps by looking at another mentor who does the same thing (shows rather than tells character feelings) in a slightly different way.

This is another short excerpt of a familiar text and gives our writers an opportunity to practice a new skill right away.

“We have another excerpt from ‘Popularity’ by Adam Bagdasarian. You’re going to try noticing and naming like we just did.”

We read the text aloud and guide students toward noticing what the author did. This is highly scaffolded, since we expect students to notice again that the author uses details that reveal a character’s feeling, but different kinds of details.

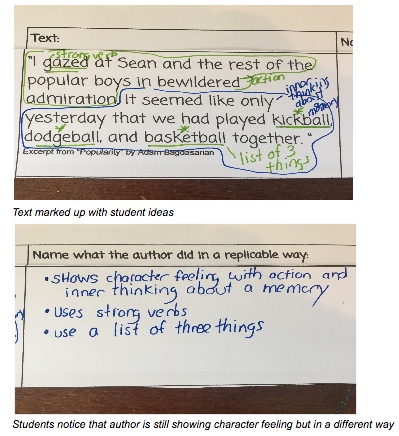

Donovan jumps right in: “I think he’s feeling jealous in this part because it says he was ‘gazing’ at the boys like he wanted to be with them.”

Then we guide students toward the next step of naming how the author did this:

“Donovan, I was thinking the same thing. But Adam Bagdasarian didn’t come out and tell us that he was feeling jealous. He shows us, just like James Howe. Now we need to read carefully and try to figure out how Adam Bagdasarian showed us this. What kind of details did he use?”

“Well, he told how Sean was gazing…”

“Right. Can we give that a name so that we could use it in our writing?”

Most of the time when students try this step, they name something specific to this particular text until we guide them to name the work in a replicable way.

“I think it’s an action?”

“Great! Now that we’ve named it, we could use it in our own writing to show how a character is feeling. Let’s mark up the text.”

As students turn and talk, we mark up the text and create a list with the details they notice. They notice a different combination of details that they can use to show character feelings. They also notice some other author craft, like the strong verb choice and the list in a series.

Step 4. Try it out in a shared piece of writing.

Since this work is new to our students, we use a gradual release of responsibility by having them try the work in a piece of shared writing as we work together.

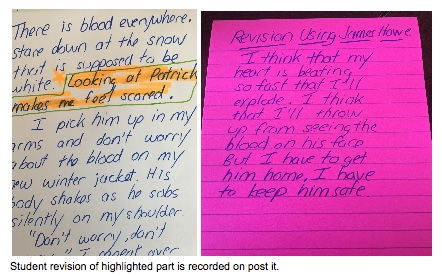

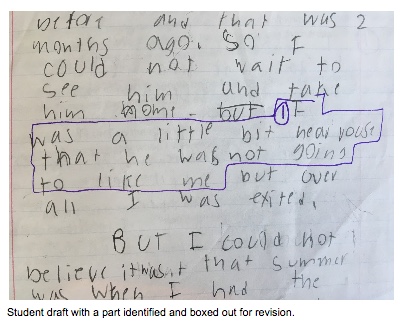

“This is a piece of writing that Mrs. Barnett’s been working on. When she reread it, she noticed a part where she just came out and told readers how she was feeling. We’re going to box this part out, and then we want you to help Mrs. Barnett use James Howe’s writing to help her revise.”

We remind students about what we noticed in James Howe’s writing and talk a little about Tara’s actions and thinking in this part of my story. Then we ask students to turn and talk about how this could be revised in the style of James Howe. We have students share their revisions and revise the writing under the document camera. Throughout this discussion we guide students toward mimicking not only the types of details the mentor authors use, but also the craft.

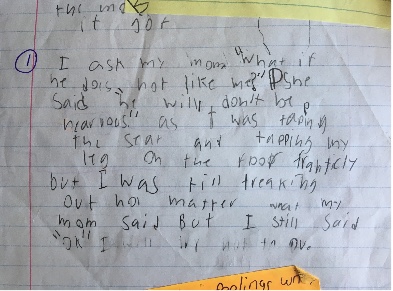

Step 5. Apply what we’ve learned to our own writing.

Before leaving the lesson, students are asked to find a place in their own writing where they have either told a feeling instead of showing or a place where they think it’s important to reveal how they’re feeling. They box out this part before heading off to work independently. Throughout the independent work time, we leave our shared work displayed on the document camera and wait a few minutes for students to settle before beginning conferencing.

Trying this work in their own writing is an important next step. We make it clear that today we expect all students to try this revision in their own writing. We incorporate choice by having two mentor texts to try it with. We also don’t require students to use the revised writing. When our students eventually publish this writing, they’ll include their drafts with revisions so that even if some revision doesn’t make it into the final piece, we can see where they’ve tried the work out.

On this day, some students went off and tried the strategy three or four times in their own writing, and others tried it once and then revised in other ways they knew.

Ultimate Goal: Using Any Text as a Mentor Text

We know how revising using a mentor can lift the level of student writing in dramatic ways. We also know that it can be hard to transfer what we see in a piece of published writing into our own writing. These scaffolds help our writers with the heavy lifting of mentor text work. They guide students to notice what the author is doing and how they do it before they try it in their own work in a focused way. We’ve done lessons like this to help writers see how they can vary details, write leads, and use punctuation.

But scaffolds are meant to be temporary. Just like they do on a building, scaffolds are there to support and then they’re removed. Our ultimate goal is to help students develop the skills they need so they can use any text as a mentor. We want students to be able to recognize writing that moves them and be able to name how so they can do it themselves long after they’ve left our classroom.

Tips for Teachers on How to Scaffold Revision with a Mentor Text

- Choose a short excerpt (a paragraph or less) of well-written text.

- Use drafts to choose a focus for revision.

- Give students a copy to keep in notebooks.

- Name the steps explicitly.

- Give opportunity for shared practice.

- Have students find a place to try it in their own writing before leaving the lesson.