When I transitioned from 18 years as a primary teacher to a 4th grade classroom, I started thinking about how I could use the same successful strategies for launching writing workshop to support my students as I introduced science notebooks. I wanted to find ways students could begin writing like scientists with authentic experiences and community support from their classmates and me. Children understand the world of fiction and see the benefits and results of writing through the work of their favorite authors and poets. But what did they know about the writing of scientists? How could I help my students gain an appreciation and understanding of scientists as writers?

I decided science writing would be a part of science time. The informational mentor texts we would read, the explorations, and the many shared learning experiences are the anchors for a unit called “Working like a Scientist.” We study ecosystems found in our outdoor learning lab, describe the relationships of food chains and webs, and identify how plants and animals present unique survival adaptations.

No matter what scientific topic is slated for the beginning of the year, it can serve as a platform for thinking and writing like a scientist. I had a hunch it would be vital for children to link writing to their actual science experiences; connections help children remember and understand the big ideas of science as they explore the world around them. So my question became: How do scientists write?

The unit asks for children to redefine their ideas of scientists, viewing scientists as learners, explorers and writers. As we considered the work of scientists, some of our questions kept us on track include:

- Why would a scientist keep a notebook?

- Why would scientists write about their experiences and thinking?

- What would entries look like?

- What are the writing features and forms used by scientists?

- How will I use a science notebook?

- How will the notebook help me as a learner?

- Are notebook pages finished products or will they be used to write pieces to share with others?

I want my students to experience the tools, skills, craft, and end products of science writing. Writing like a scientist is different from creating a narrative or magical story and understanding those differences seemed as critical as discovering the similarities.

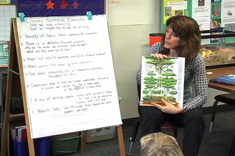

Mentor Texts

Our time spent outside exploring ecosystems is combined with mentor texts. These are some of the first books we look at together. I use the books to highlight different aspects of science writing we’ll be thinking about throughout the year.

Crawdad Creek

By Scott Russell Sanders

Illustrated by Robert Hynes

A sister and brother take the reader on a hike and introduce the amazing elements and living creatures found in and around a lively creek. The illustrations are scientific and beautiful at the same time.

I selected this text because it shows children the many treasures waiting to be discovered in local habitats and it reminds children that priceless experiences are outside, waiting to be discovered.

The Snail’s Spell

By Joanne Ryder

Illustrated by Lynne Cherry

With beautiful language and detailed illustrations, the reader is magically changed into a garden snail and takes a “field trip,” experiencing a day in the life of a snail.

I love how Joanne Ryder’s words transform children’s perceptions of a simple creature like a snail and help them realize how many extraordinary events are happening right outside in the garden. Lynne Cherry’s detailed illustrations are a nature’s Eye Spy event not to be missed!

Salamander Rain

Written and illustrated by Kristin Joy Pratt-Serafini

A boy named Klint is a member of a group called Planet Scouts, an environmental club for outdoor learners. The book documents Klint’s experiences as a Planet Scout, tracking his learning in a journal and scrapbook format. It is packed with information, scientific drawings, and ideas for outdoor learning.

This appealing text provides an introduction to outdoor exploration; the format provides many interesting models for blooming writers as they think about how they can share their science learning and experiences with an audience.

Chipmunk at Hollow Tree Lane

By Victoria Sherrow

Illustrated by Allen Davis

This book is part of the Smithsonian’s Backyard series, a collection of books that take you into the natural rhythms and cycles of animals, allowing the reader to spend time alongside favorite creatures.

I use this book because children see certain animals, like chipmunks, outside but often do not know how these creatures live. Chipmunk at Hollow Tree Lane lets a child see how a chipmunk spends one of many days preparing for the coming winter. The gorgeous illustrations are packed with as much information as the beautiful, yet informative language of the text. I LOVE this entire series!

Under One Rock: Bugs, Slugs, and Other Ughs

By Anthony D. Fredericks

Illustrated by Jennifer DiRubbio

Paying attention to the many details found in nature is described through rhyming verse in this cumulative tale told by a child who turns over a rock and discovers the creatures dynamically living under or near a rock.

I use this book because the introduction page is a friendly letter from a spider inviting people to visit her meadow and other green spaces. The friendly letter provided is used as a mentor text when my own students invite their families to our Outdoor Celebration where students serve as naturalists and tour guides in our outdoor learning lab. This book also is a terrific source for considering micro-habitats which might be waiting to be discovered in our own backyards.

These mentor texts were combined with writing opportunities. We realized if we were to be effective scientists, we would need to learn how science writing could help us. Children needed to see science writing not just as a finished product, but as a flexible set of tools in the explorer’s backpack. Science writing can be a tool to gather information or collect questions, as well as a means of holding and sharing ideas with others. These are big concepts for students to master, so I knew I needed to break this process down into smaller experiences.

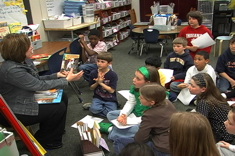

Capturing Ideas Like a Scientist

In the beginning, I decided not to share the polished, finished work of science writers. Instead I gathered examples of the kind of writing scientists use when they are getting started. A few of the writing examples included:

- Anecdotal notes taken by my friend who works at a zoo. The notes described the social behaviors of wolves when enrichment activities (blocks of ice with treats inside!) were introduced to the wolves’ habitat on a warm evening.

- Anecdotal notes taken by my students when we introduced our guinea pig to her new straw hide-away hut. The notes recorded her actions, sounds, and repetitive behaviors as she explored her new house.

- A student generated list of plants, organisms, and other organic matter found in pond water samples. This list was based on observations at our school’s outdoor learning lab.

- Observational notes of a local bird watcher who recorded several sessions with a flock of crows when he kept placing odd, shiny items on a stand next to a feeding station. He wanted to see which items were taken and left behind by the crows. They took a set of keys, foil wrappers, glittery hair doodles, a lighter, and scrap aluminum. They left behind Tupperware container lids, hair doodles, plastic wrap scraps, toy plastic keys, and scrap wood.

My goal in sharing these informal, real-world examples was to help students see the range of ways working scientists and other students write to record new information in formats that best captured the gist of the ideas. The science notes we looked at together included:

- sketches

- accurate models with labels

- lists of facts

- collections of questions

- anecdotal observations

- graphs and tables of gathered information

- notes on video clips

- captions on photographs

- timelines

The different ways to capture information were important for my students to study, and then have a chance to use during their explorations of ecosystems. My hope was that the experiences would lead to understanding.

As we used our science notebooks, children realized that our notebook pages might not look like much to an outsider, but they meant a great deal to us as scientists. I needed my students to understand that the forms of writing used in their science notebooks were just as valuable as the stories in their writers’ notebooks. They needed to see their notebook entries as equally valid forms of writing, holding the seeds of future writing ideas. Just like caterpillars waiting to transform, ideas take time. The gathering of ideas was as important as the creative process used to write polished products. Capturing information in our notebooks would help us be effective scientists. Finally- we had a good reason and place to begin our work of learning how to be science writers.

When I started thinking about the “Working like a Scientist” unit of study, my work was shaped by my own instructional questions:

- What did my students understand about science writing?

- What experiences did they have writing as scientists?

- How did students view the process of science writing?

- How can we approach science writing with the same developmental integrity as writing workshop?

- How will the work affect our students as learners?

If I expected students to share their scientific understanding of the world through writing, they would need to learn how to read, write, and think, as researchers. Students would need time, support and authentic reasons to write as scientists during their science classes. In future articles, I will document how we approached writing like scientists while exploring the ecosystems of our school’s habitat. Be prepared for adventure with lots of learning, mud, questions and laughter. Scientists are explorers and writers and they never know what lies ahead, but they can be prepared when they travel with a notebook in hand and boots on their feet.