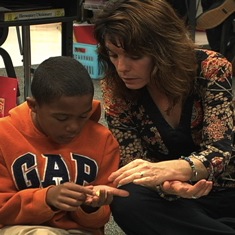

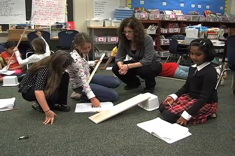

Today I observed my students scattered around our school's outdoor learning lab. I wandered from group to group, from micro-habitat to micro-habitat, thrilled with their focused energy, thoughtful conversations, and authentic writing. I visited with different study teams, conferring with children about their discoveries in small and often overlooked outdoor spaces.

"Did you ever think that a rotting log could be so interesting?" Pete asked as I sat next to him and Sam, his study partner. The two boys were sitting on a grassy patch facing a fallen apple tree. They had decided to study the life, systems, and relationships found in and around a decaying tree. The crab-apple tree, knocked down during a windstorm several years ago, had been purposefully left behind for exploration in our outdoor lab.

"So what are you guys doing?" I casually asked, trying to cover up my excitement as my eyes skimmed over the open notebooks before me.

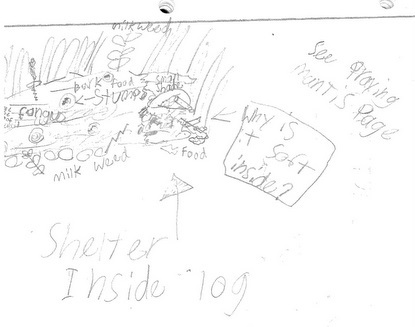

"Well, we decided to use lists as we study our micro-habitat. We also wanted to draw a model of the tree with labels and question boxes. " said Pete. "We want to make observations and start some lists that we could use later, but we really thought it was important to make an accurate diagram of the dead tree with lots of labels because not many people think about rotting trees as a place for life. We want a map to help us remember what we saw and where we saw it. See?"

I studied the accurate drawings displayed on each of the boys' pages. There were question boxes with arrows leading to curious features on the fallen tree marking their wonders. I saw carefully placed identification labels marking important sections of the rotting tree. Wow.

"We've started with our sketch, but we'd really prefer to use the camera tomorrow so we can get a good picture, and then add the important labels and questions that will help our readers understand and notice what's going on here," added Sam.

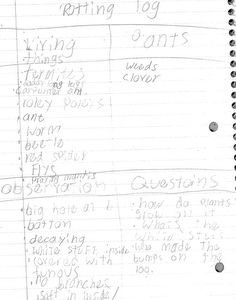

"And see this two-column table? This is so we can list the living creatures and plants we're finding in and on and around the log. We're going to put a star by the ones that actually live in the dead tree," chattered Pete.

"But we're not sure about the mushrooms . . ." added Sam. "Do you think we need another list for those? Are they plants? Or what?"

On a perfectly sunny September afternoon, I could not have asked for more confident answers and questions from two young writers with serious intentions.

"We may need to crack part of this tree open so we can see the insides . . ."said Pete. "Yeah," added Sam, "and then we'll have a great cut-away . . ." The two boys looked at me. "Ummmm, we're okay Mrs. Smith. We know what we're doing." Sam murmured, poking his pencil into a crumbling section of the dead tree trunk . . .

I smiled as I was dismissed from the conference; at this point, I needed to give them space and time to work as writers. Their parting words were really a polite way of saying: We really do not need you right now. Turning kids loose with time and reasons to work as writers is so important for learning.

"Let me know if you discover anything exciting." I replied, leaving the door open for future discussions. Looking as the two boys as they returned to furious note-taking and conversations, I think the only thing they might need over the next few days from me was my key to the tool shed to get a crow bar when they finally decided to crack open up the rotting tree.

These boys were writing like scientists — gathering ideas in an organized way, using visuals to hold and communicate information, and asking meaningful questions. Most important — they were writing with their own purposes and intentions.

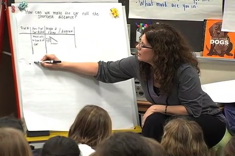

Expanding Options for Science Notebooks

I launched our September science studies with a unit called "Writing like a Scientist." My goal was to help students understand that active scientists use writing in a variety of purposeful ways. While studying the present ecosystems in our schools land lab, students would learn first-hand how scientists gather information while asking questions to guide their learning. I wanted them to discover that writing was a tool and a medium to showcase their learning.

At the end of the unit, students will be hosting an open-house for their parents, community members, and younger students. Presented as "naturalists" by the various micro-habitats found in our outdoor lab, students will educate visitors about our backyard oasis for wildlife secretly living in the suburbs. Students' research will also be compiled to create a student made Visitors' Guide for the outdoor lab.

What kinds of food chains and webs can you find in a flower garden?

How is a flower designed to welcome bees?

While providing authentic reasons to study and write about backyard micro-habitats, I want students to experience outdoor discoveries, while using scientific writing to hold, expand, and deepen their understanding of ecological concepts. I want their work to show what they had learned and how their discoveries lead to new questions for continued learning.

With big aspirations, we started this project the second day of school. I asked my students: How do scientists write? We spent several days looking at a variety of mentor texts from our classroom library, field notes of real scientists, and the visual information often presented in nonfiction texts. I split our science time in half; some of the time was devoted to studying and reading mentor texts and the other half was for free exploration of the outdoor lab, granting children time to just be outdoors.

As the kids explored, I walked around with a clipboard documenting their amazing discoveries, knowing that the list of "wows" would come in handy when we started the micro-habitat studies. Here are some of the "wows" I noted on my clipboard to share later with everyone as I listened in on the students' conversations:

- Whoa! Look at the algae on the pond. I wonder what lives under the algae?

- Why is the creek water so murky and muddy here, but clear over by the cattails?

- Why do cattails grow into the water?

- Why do some animals cling to the creek rocks? Don't they get smooshed?

- How do water striders and whirligig beetles stay afloat when they travel on the water?

- How did that big mess of leaves get in the branches of the oak tree…is it a nest or just a mess of leaves? Who made the nest if it's a nest?

- Why does this knocked down tree have so many holes? The holes are all different sizes too!

- Why are the milkweed leaves so ragged on this plant,? This milkweed plant looks great. The two plants sit side by side. What's going on?

- Why does dirt smell like dirt? Why does wet dirt smell even more?

- Why does the prairie garden look like someone just forgot to weed the garden and cut the grass?

Free exploration was important because students needed time to gain a value for the space if I expected them to study this habitat in depth. Falling in love with this space generally takes about five minutes . . . but several days made the relationship solid!

Our time with mentor texts was worthwhile. After looking at the field notes drafted by a zoologist working with wolves, students noticed the purposeful organization of the scientist's notes. Her observations were placed in columns; categories of observed wolf behaviors before, during and after blocks of ice with embedded "wolf treats" were introduced to the zoo's wolf habitat at dusk on a July evening. Students realized the table of information was not just a way of being neat. It showed a way of thinking. Students decided that lists could help their micro-habitat studies. "So much is going on out there!" giggled Maria. "We need to be ready to deal with so much information!"

While reading the book, Crawdad Creek, the children noticed the story took place over the four seasons. They documented various wildlife discovered by the characters on creek expeditions. Students also asked to reread the book in order to sort the animals into seasonal lists.

"Why?" I asked.

"So we can try making lists too," said Sasha as she flipped to a new page in her science notebook. She divided the clean page into four tidy columns. "This book could really help us to think about our own study areas in the habitat. We may need to sort the plants and animals into different groups so we understand the food chains and webs in the micro-habitat we're studying. Sorting keeps me from getting confused."

"My writing is so big," said Brian," I'll need to make a two-page spread for my table or it will be a mess . . ."

"Good thinking" I complimented. "You know what you need as a scientist."

We spent time with models or info-graphics — accurate pictures that conveyed information with visuals and text. The One Small Square Series showed models, cross-sections, cut-away diagrams, and close-up views of life waiting to be discovered in common places. Students learned the value of info-graphics and how the visuals were just as important as text for holding and communicating information.

Starting with a few key mentor texts, students discovered powerful and practical ways to write and study their micro-habitats of choice. As they explored the outdoors, these writers tested out how useful lists could be as an organizational tool. They found out first-hand that info-graphics showcasing vocabulary, ideas, and questions captured their knowledge and wonders. My goal for students to gain writing strategies that could be carried beyond the "Writing like a Scientist" unit seemed possible.

I had only one wish on that perfect September afternoon as I witnessed my students writing. I wanted the scientists and authors of our wonderful mentor texts to observe my kids at work. I wished those adult writers could see how their expert words and informative visuals helped my students gain more than scientific information; their work inspired and supported the growth of my young writers.

As I walked away from Sam and Pete near the rotting tree I heard a splash from the creek and the inevitable "Oh no . . ." When you work with children around water someone or something is bound to get wet at some point during the adventure. I saw Natalie sprinting away from the creek toward the school building door. "Are you okay?" I called.

"My notebook fell in the water . . . and I know where the extra notebooks are . . . so I'm going to get a dry one. I need to hurry — we're mapping the area where the tadpoles rest and we're trying figure out if they prefer the sunny or shady areas." Natalie called over her shoulder. "You can stay outside-I know where to find a dry notebook."

Laughing, I looked across our priceless outdoor lab and wandered off to find someone else who did not need me.