I had an observer in my classroom a few years ago who said, "I love how independent your students are during the workshop. They're such independent writers for fourth graders." I smiled and said thank you.

My mother always taught me to accept a compliment by saying "thank you" and smiling. Then in your head say "I know!" But to be truthful, I didn't know. I looked at this teacher and honestly asked, "What do you mean by independent?" Because I didn't feel the students were very independent at all. I wondered if I were gone a week, could they carry on in writing workshop with their own set of goals and plans? What if I had to be gone a month? Let's say I was on a jury of a juicy court case and I was sequestered, unable to get lesson plans out to the substitute for weeks. Could my students carry on and determine what writing they want and need to do? Would they independently study mentor texts and demonstrate all they know about writing well?

The teacher pointed out the following things:

- Kids left the minilesson ready to write and got right to work.

- When students had questions, they asked another writer or wrote the question on a sticky note until I could get to them.

- When I conferred, many students took control of the conference already knowing what they needed from me.

- When students were "finished," they knew to start a new entry or a new project.

I have to agree that's pretty impressive in terms of routines. My students typically are working independent in our writing workshop. Not always, but much of the time. Yet that doesn't make them independent writers.

What is True Independence?

When I think of independent writers, I think of Bella. She was a third grader in my class last school year. As the year went on, we studied how to write a newsletter, and our technology person showed us a software program to whip up colorful newsletters in a snap. From December through the rest of the year, Bella wrote her own weekly newsletter at home. She wrote about what was going on at school or in her family. Her mom told me how serious Bella was about it, and she had some of her friends write articles for her too. Bella is an independent writer.

When I think of independent writers, I think of Sarah. Another third grader, Sarah went against the grain. She didn't cause problems, she just saw things in unique ways. When we were working on nonfiction feature articles, Sarah wanted to do something different. She found the computer program Comic Life and proceeded to write a graphic story of a hamster talking about how hamsters live around the world. She then made her hamster a correspondent for a famous newsmagazine.

And then there's George. George is witty and creative. Once he found a way to model an informational picture book from Cloudy With a Chance of Meatballs, he was on his way. Complete with puns and metaphors, his story about a lonely black hole went beyond my expectations (and teaching points).

So what makes these kids different? How do we make them the norm? I think defining independent writers is a start. In kindergarten, I define independent writers as those children who can actually write without help. They stick with their story ideas, and they can use pictures, letters, and words to make meaning on the page. But what does independence look like in the upper grades?

For me, independent intermediate writers are children who:

- easily find their own topics;

- search out ways to write like what they want to read;

- find technology or mentor texts to support their writing;

- envision an audience and write for that audience;

- write and publish for reasons beyond the classroom; and

- have a plan for what they want to do next.

This list seems daunting. Even as I wrote it I caught myself thinking . . . really? Is it possible to move every child to a place where this is the norm? Yet thinking back to how we used to teach reading — with SRA kits and an anthology that had very little literature that could be found in the world outside a textbook — I'm sure some teachers used to believe that not every kid would learn to love reading. Yet fostering a love of reading in every student is now an expectation in most classrooms. It's possible for us to move young writers towards greater independence. More important, I think it's necessary.

Getting to Independence

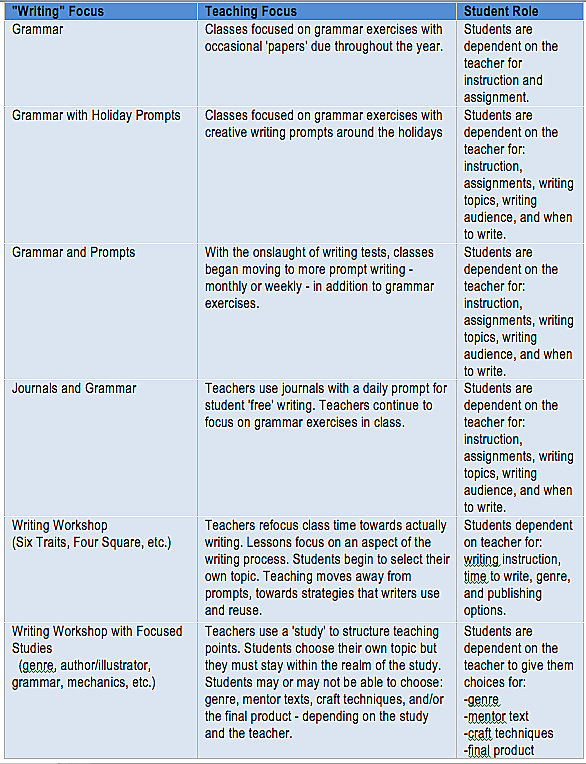

We have to find ways in our teaching methods to support students with independent writing projects. We've come a long way from grammar-focused classes and a creative writing prompt around holidays, to using a writing workshop model where children actually write on a regular basis. I've thought back over the kinds of teaching I experienced as a child and how my writing curriculum as a teacher has changed through the years.

Bridging the gap between student dependency on the teacher for choices and students making choices on their own in writing is an essential next step for writing curricula everywhere. In his book Grown Up Digital (2009), Don Tapscott points out that the net generation (the kids we're teaching NOW) has more choices than ever before.

For example, on my son's recent Christmas list, he wanted to make his own Nike shoes. What?! I went to the Nike website and there it was — make your own shoes. The customer chooses the color scheme. This option applied to not only shoes, but book bags, athletic gear, and more. I remember when the purple swish came out for Nike. It was the hottest shoe around. I had to wait six months to get a pair! Now I can just design a pair of shooes in a favorite color and in ten days, it's on my doorstep.

What does this have to do with writing? Kids are growing up expecting to make their decisions with a level of choice and specificity unheard of just a few years ago. They are customizing their experiences, and learning to make choices among myriad options. That takes discipline and a strong sense of self. Then in school, we give them few choices (or a controlled set of choices), which is not reflective of what they'll be able to do in the future. Choices matter in life, and in writing. We need to find ways to hold our students accountable for making choices that will define who they are as writers.