With each passing year, I accumulate larger piles of data about my incoming middle schoolers: spelling inventory scores, Developmental Reading Assessment scores, state test scores, and district diagnostic scores. Yet I’ve felt less and less certain that I am getting all of the information I need about incoming students. It doesn’t mean that an additional paper and pencil assessment is the answer, though.

These personal reflections and concerns have been driven by:

- the blogs written by elementary colleagues that show me the possibilities for amazing literacy communities

- the policy changes that are nudging some middle schools back to the junior high model, where community is secondary to subject matter

- the changes in my own life, as a mom who is now considering what it would be like to transition from a school my child had attended for six years, starting at age five, to a school of nearly 1,000 students and many unfamiliar staff faces

When it comes to transitioning my sixth graders into middle school, I’ve always paid close attention to reading transition folders, student interest surveys, and beginning-of-the-year letters parents write to me about their children. However, I’ve always gathered all of that information post-elementary school, including professional conversations with elementary teachers only when major red flags were raised.

I was starting to realize that underneath the piles of well-intended paperwork, I was missing valuable insight into my students’ fifth-grade experiences, and then losing valuable momentum from elementary school. What successes had children experienced that were lost in the sudden shift from four elementary schools to one big middle school? I needed to consider new, manageable ways to personalize the transition of my 80+ students from elementary to middle school.

I’d already been in professional conversations with Maria Caplin (a fifth-grade teacher in my district) over the past few years, touching base with her when I had concerns about a student, and carefully considering the thoughtful notes she always included in her district reading folders.

Maria and I began a series of conversations about concerns we both had about the fifth to sixth grade transition, and we decided to experiment with ways to improve it. The idea we settled on was something we called “transitional conferring.” Maria would recommend five students for a pilot program and open to me her end-of-the-year reading conferences, which would also include students’ parents. I would have a chance to see my future students’ thinking in action in a setting where they were already comfortable. Our hypothesis was that there would be much power in having the students and me on the same page about their current lives as readers and writers; it would give them more accountability and ownership for the progress they made in fifth grade.

Logistical Obstacles

The first obstacle was in student selection. In order to ensure that students from all four feeder elementary schools were evenly distributed through the four language arts classrooms at our middle school, Maria and I could not simply move her entire roster of students right into my classes. We proposed and were approved for the five students whom we could hand-schedule into my roster, for the purposes of piloting this work.

We had to be very thoughtful about our purpose, which drove how we selected students. We decided to choose students who had made a great deal of progress — measured by a variety of assessments, including Maria’s professional judgments supported by classroom documentation — but who, by virtue of personality and/or by their proficiency relative to some other students, might be prone to slipping through the cracks and losing their momentum in the leap to sixth grade.

Maria and I had to be prepared to answer the question: Why these kids and not the others? Surely if this was a good idea, then all students should be offered the opportunity. We framed our work as a pilot study, which meant that we would take careful notes about our process and develop recommendations that could be applicable to broader student populations.

Making It Happen

After we’d received permission to schedule the students into my sixth-grade classes for the fall, Maria and I moved quickly to get parents on board and to coordinate our schedules so that students, parents, and both teachers would be present for our “transitional conferences.” We made available conference times before and after school, and we also found common time mid-day so I could make the short drive to the elementary school for a half-hour meeting.

We sent a joint letter to the five sets of parents, letting them know that due to their children’s great progress in fifth grade, we had selected them for an opportunity in sixth grade to build on that progress. We let them know that the expectations and opportunities would include:

- students and parents meeting with us at the end of the school year

- students meeting with us again before school started

- students having the opportunity to know me ahead of time, so they could check in with me over the summer about summer reading or middle school questions

- students and parents would be offered the opportunity later during the sixth-grade year to meet with both Mrs. Caplin and me

We framed the end-of-the-year transition meeting as a student-led meeting, during which each student would “share his or her fifth grade literacy celebrations, as well as his/her reading and writing goals and needs for sixth grade.”

A few of the parents had older children and expressed an eagerness to help us make improvements to the transition process. Parents without older children were happy to become more familiar with the middle school themselves. Students were concerned about standing out, but I assured them that when they started school, I would make no indication that I already knew them. Maria and I were thrilled to have everyone on board.

Powerful Connections

The most obvious and immediate benefit to our pilot group was that I built relationships with families before students had even exited fifth grade. The transitional conferences with students and their parents were more comfortable and felt less punitive than our middle school, whole-team, concern-based conferences, which are also limited in number because we have 150+ students on our teams. Because these transitional conferences were framed around student successes and anchored in pieces of work students wanted to show me (grades never entered the conversations), the conversations also showed parents how reading and writing conferences work. I wondered how I could make more room on my plate for these valuable conversation with more families in the future.

By visiting Maria’s classroom, I also had access to students’ readers notebooks and word study notebooks, as well as to Maria’s reading conference notes she kept on Evernote. I continue to reflect on how those pieces of more holistic information could be transferred to the middle schools in a way that would be helpful but not overwhelming to sixth-grade teachers.

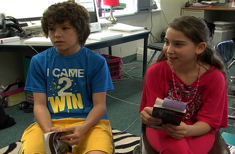

I was pleased to discover some expected benefits as well. I enjoyed receiving positive feedback from parents about being able to send my new students notes over the summer, something that’s not been logistically possible in the past when I received rosters shortly before school starts. Maria and I met with our five students for pizza a week before school began, so in addition to getting to see them in action as we set up our classroom library together, I also found it helpful to see them interact comfortably in an informal setting with the teacher with whom they already had a relationship.

Through our informal before-school interactions, I learned personal information about students that I may not have discovered when they assumed their “big kid” sixth grade personas. I was surprised to hear one boy rave about The One and Only Ivan and about how much he loved animal books — once he hit middle school he was reluctant to share information. I was touched to see another boy, who also assumed a very confident identity as soon as the year started, in a near panic when Maria had not yet arrived at our pizza party. By virtue of the students’ and my head start on our relationship, I became for a few months their initial contact for questions unrelated to literacy, including small matters (lockers!) and bigger ones (social problems).

Implications

Because of our pilot program, I had the opportunity to spend chunks of time in Maria’s classroom at the end of her school day. The time gave me an appreciation not only the power in watching a talented veteran teacher in action, but also for the power of shared language. I wondered, what does Maria say that I could also say to trigger students’ memories and help them retrieve the literacy tools they developed in her classroom? The few “Maria-isms” I jotted down during my observations have come in handy more than once this year. I remember the face of one of her students — a young man who struggles mightily with reading — lighting up with recognition, and his hand shooting up with confidence, when I used one of Maria’s terms to talk about identifying important ideas. This finding leads me to think that we need to have bigger districtwide conversations about shared language. There are more than fifteen elementary classes that feed into our school, and we could develop even a few common understandings that would help our students transfer their thinking on to middle school without losing the individuality of each of those classrooms.

Even without the specifics of shared language, I found that building trust with Maria so she’d be comfortable having me in her room gave me many “aha”s about what happens in fifth grade. I have a better understanding now of what students and parents are feeling coming into sixth grade, and though it’s not appropriate or possible for me to duplicate the elementary experience, I do have a better sense that I need to help everyone bridge the leap.

Because of the time I’ve spent in Maria’s building, Maria’s teaching partner and I have also begun to have candid, professional conversations about ways to support a few of her former students, conversations for which we must have first established trust and mutual professional respect. These conversations go hand in hand with the biggest implication of all: my students are more than the data and records with which they arrive.

Living this realization does not require the logistics we were able to coordinate with our pilot group. Yet the pilot group has taught me that as a sixth-grade teacher, I am responsible for:

- building trusting, collegial relationships with my students’ fifth grade teachers

- initiating respectful conversations with those teachers about their students’ elementary school successes, not just their struggles, and not just about the outlier kids whose information dominates transitional meetings

- attempting to build on my students’ anecdotal successes from elementary school

- being mindful that for families, the transition to middle school is a giant one, and considering how to make it a smoother one

Whatever the next steps of our pilot study, I have a readjusted sense of priorities, a fact that I know will benefit all of my students. I will continue to be analytical and thoughtful about the hard data I receive about my students, but I will also continue to find room on my plate for conversations with my students, their parents, and their teachers as we all navigate the enormous transition from elementary to middle school.