I just feel like I have so many students who need help.

I end up sitting with just a few students and never see the rest.

There’s never time for me to figure out what students need so that I can pull a small group.

These were concerns shared by one kindergarten teacher in a planning meeting during our coaching cycle. Kate had heard them echoed by others, so they definitely weren’t unique to this teacher’s classroom or even her grade level.

We love the predictability and structure of workshop teaching, and in it, found flexibility and felt empowered to make decisions to meet the needs of students. Many of the teachers we collaborate with during coaching cycles, though—most of whom have taught workshop for less than five years—feel like the predictability and structure of workshop teaching means rigidity. They believe there are rules—right and wrong ways to do things. And although it’s true that certain core beliefs have to be in place for workshop to run effectively and as intended, it is also true that workshop teaching requires teachers to be flexible to meet the needs of students.

When teachers mention an approach they’d like to try during workshop but are unsure whether it’s okay, we usually ask, “Is it what your students need to be successful and more independent?” They always say yes, they think it would help the students. “Then it’s definitely okay,” we answer.

Spend Time Each Week Collecting Data Through Observation

The first step to knowing what students need, of course, is having some kind of data (formal or informal) that highlights that need.

Most teachers wouldn’t say they have a shortage of data; many of the teachers I work with feel like they have too much, and not enough time to sort through it all. One way we have tried to address this is to use part of the workshop time to gather and then quickly, on the run, analyze the data to find some patterns to drive small groups or conferences that day and in the days that follow.

With the kindergarten teacher who expressed difficulty with finding time to look through her students’ writing to find data for her teaching, we discussed using five minutes once a week to circulate among her students and make notes of some patterns she sees in their writing. This can be done at the start of their independent writing time so that it serves two purposes: gives the students a chance to get settled into their work more independently, and gives the teacher time within the writing workshop to gather data. In this way, we’re deviating from the traditional structure of conferences and small groups during independent writing time, but we believe it’s time well spent, because the result is more independent students and more tailored teaching.

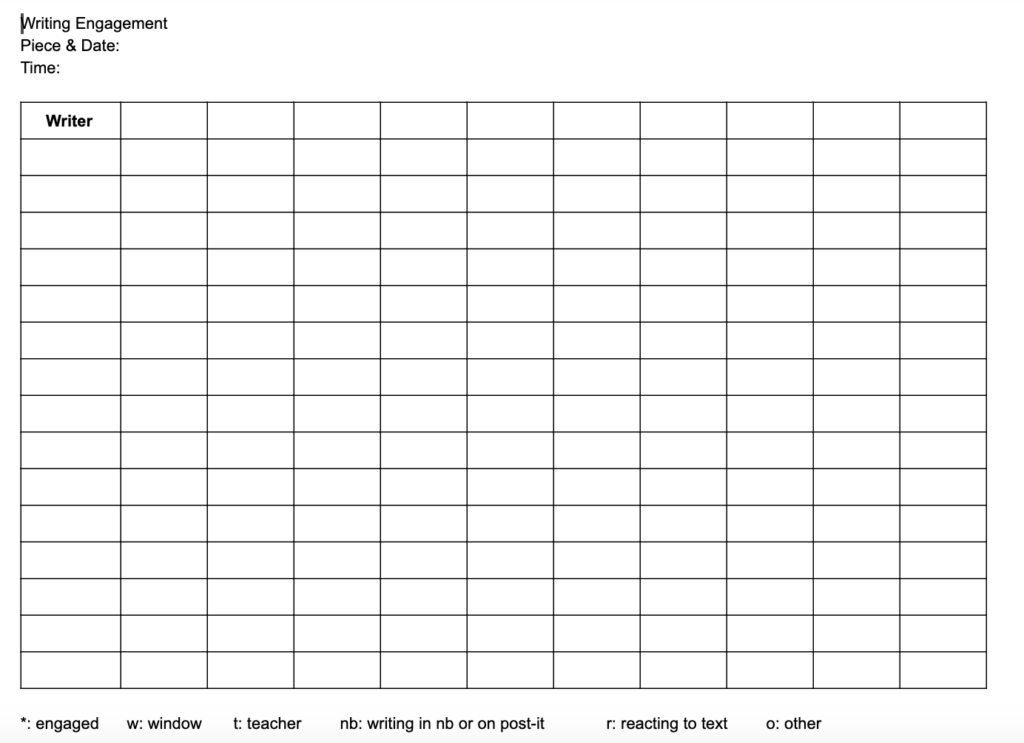

In first grade, we tried a more formal approach with an engagement inventory. The one below, learned from Jen Serravallo, is one that teachers often use during writing-on-demand days at the beginning and end of writing units. Newer to them was the idea of using it during the unit.

Similar to the kindergarten teacher, we tried using it for 10-15 minutes during one writing workshop period at the beginning of the week. Doing this weekly or every other week would allow for more than enough information around writing behaviors and engagement to inform conferences, small groups, and minilessons.

In both the kindergarten and first-grade classrooms, we also tried using a printed copy of the unit’s chart to collect data more angled toward the content of the unit. We put student initials next to the strategies on the chart that we saw them trying in their books so that we could reinforce and lift the level of the work during conferences and small groups. You could also use the chart to put student initials next to the strategies that are absent in their writing.

Although collecting data through observations isn’t the traditional use of teacher time during independent writing, it is valuable because it allows teachers to target their instruction more specifically. Our experience is that 5 to 10 minutes of this type of data collection weekly (or every other week or once a unit—some teachers prefer to start small and build the routine) helps us see our students in new ways and gives us new ideas for instruction.

After needs have been identified, we can make plans to teach into those areas. Here are some of the ways we’ve adapted the traditional structure of writing workshop at times to meet the needs of students so that they’re more successful and independent:

Try Minilessons with Smaller Groups

Co-teaching rooms are often more familiar with the idea of parallel minilessons, but teachers who are by themselves are sometimes unsure how that would work for their class. During our planning meeting, the kindergarten teacher decided to try minilessons with half the class to allow her to target the students’ needs more specifically. The half that she wasn’t meeting with first would continue with their work from the day before, which required a two-minute reminder about how they might get started: “Take out the book you were working on yesterday. What were you doing yesterday? Is there anything on our chart that you haven’t done yet? Tell your partner what your first steps will be in your book today. Now go get started.”

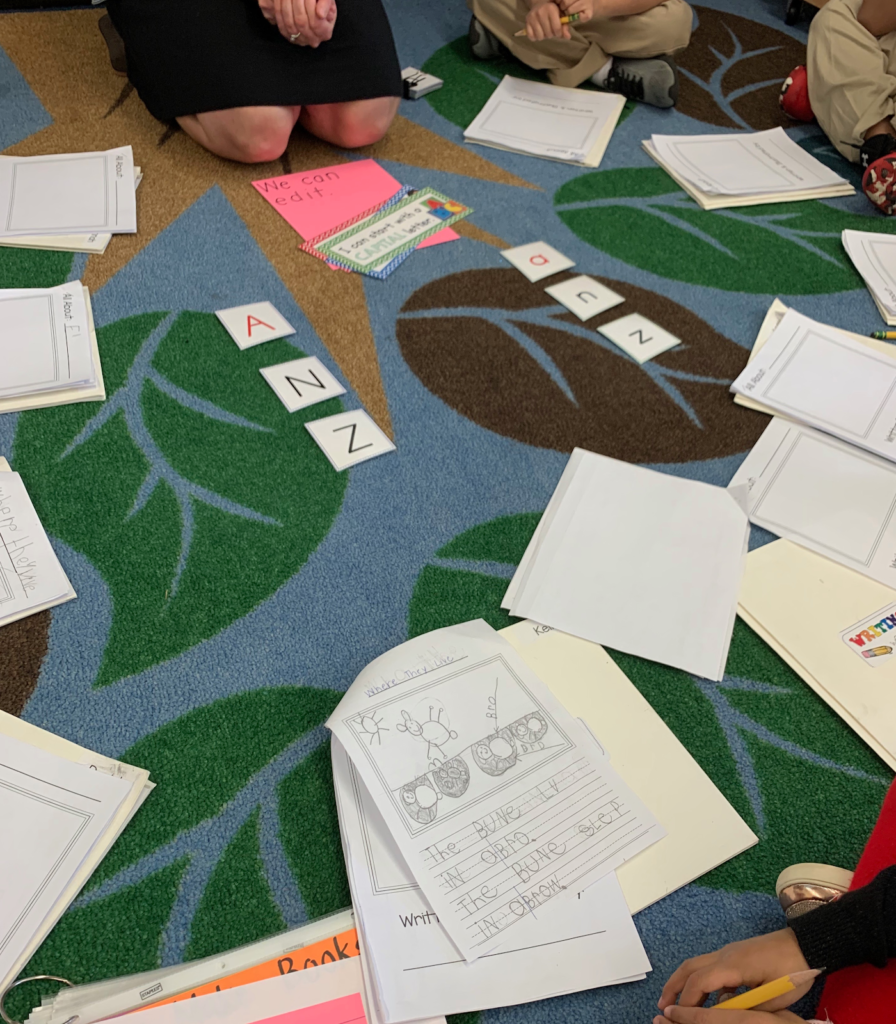

The focus for all students was to edit one of their books that they wanted to share at their celebration in a few days, but the smaller groups allowed the teacher to adjust her focus, depending on what the students were ready to consider.

Both groups started with the teacher asking them to take out their books and read through them with a lens. Both groups also gave the students a chance with guided practice, and the teacher set them up at the end of the group with something to continue as they went back to their seats.

Minilesson Group: Editing for Capital Letters

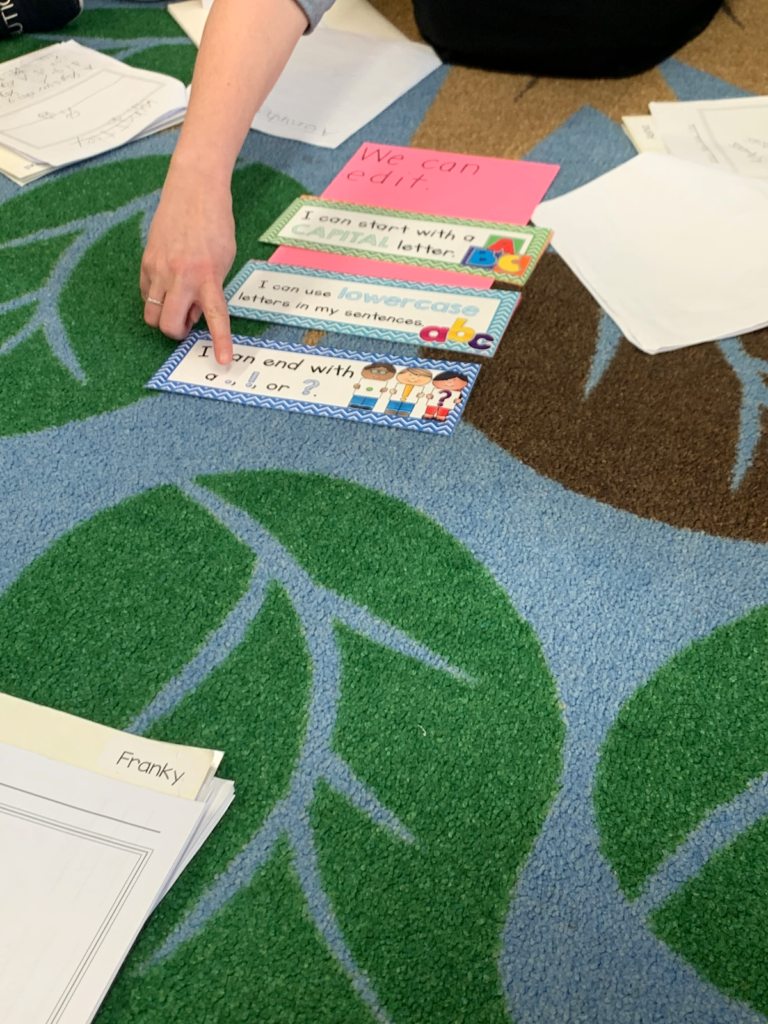

As the first group was reading through their books, checking for capital letters, we realized by listening in on their partner conversations that many students in the group didn’t understand what capital meant. The teacher quickly pulled out letter cards, pictured below, and helped the students sort them into capital (uppercase) and lowercase letters. The students were then able to return to their work to look for missing or incorrect capitals and correct it.

Minilesson: Editing with Different Lenses

The second group of writers was more independent with rereading their writing with a lens, and the teacher had some additional lenses for them to consider. She also invited them to reread with a partner to edit their writing, a method that was different from the one she used with the first group.

Both of the minilessons focused on editing and had some overlap with the lenses students were using to edit their writing. Pulling students with similar needs for the minilessons allowed the teacher to differentiate her teaching. The smaller group also allowed her to more easily notice misconceptions and adjust her teaching on the spot.

At our debrief meeting after this lesson, we talked about predictable lessons for which this structure could work—we thought anytime students are editing, it would be beneficial—and the teacher also made a note in her upcoming unit of other minilessons that it might work for.

In addition to allowing you to more easily differentiate minilessons, this approach is effective when students need more support in the minilessons, even if the delivery to the different groups is the same.

If you feel like your students aren’t quite ready for the day’s minilesson, then flip the minilesson and independent work time. In a conversation with a different kindergarten teacher who was worried about the minilesson’s focus on students independently moving to another book because most students had a little more to do in their current book, we asked if delaying the minilesson would help. “You mean we don’t have to start with the minilesson?” he asked.

We made a plan to allow the students to work for 10-15 minutes at the start of workshop so that when most of the students were almost to the end of their books, or he could see students getting up and heading to the writing center, he could pause the class and teach the minilesson then. That way, the minilesson was timed to be most appropriate for what students were ready for.

As classroom teachers, we used this variation of workshop time on days we wanted our fourth graders to try the minilesson strategy. We worked hard to teach our students that the minilessons were invitations to the work, not assignments, and that they were in charge of the choices they made as writers, including which strategies to try when. That said, there were a few minilessons in each unit that we wanted to be sure students tried. These days were often focused on mimicking mentor text moves (like revising our leads or endings using mentor texts) or new editing strategies.

On these days, we’d start with independent writing time, pulling our students together for just a few minutes so they could remind themselves what they were working on the day before, refer to the chart, and talk to a partner about their plan for that day. Then we’d move on to our conferences and small groups. When there were 15 minutes left in the workshop period, we’d have our students come to the carpet again and have the minilesson. These minilessons would often have a longer active engagement than is typical, during which we’d coach the students in trying the work right then at the carpet.

The next time you find yourself frustrated by the structure that workshop provides, and think, I wish I could do X differently, pretend you’re your own coach and ask, Is this what my students need to be successful and more independent? If the answer is yes, tell yourself, Then it’s definitely okay.