We went to a professional development session a few years ago with Elizabeth City and she gave us a name for something we have always believed – the importance of “triangulating” our data. Triangulating data means you use multiple sources of data to illuminate, confirm, or dispute what you learned from an initial analysis of one piece of data. As City writes with her colleagues in Data Wise: A Step-by-Step Guide to Using Assessment Results to Improve Teaching And Learning, “When triangulating sources, it can be helpful to draw on different types of assessments (such as tests, portfolios, and student conferences) and on assessments taken at different intervals (such as daily, at the end of a curriculum unit, and at the end of a grading period or semester), and to look for both patterns and inconsistencies across student responses to the assessments.” We always called it looking at more than one piece of data, but now it is fun to use our new big word!

As we work in districts, we talk with many teachers and administrators who are frustrated with the importance placed on certain assessments. Formal assessments are often highly valued if they are mandated by a state or a grant. Informal or interim assessments, which provide a different view of the student’s strengths and weaknesses, may not even be considered data. We believe that it can be very misleading to make a judgment about a student based on one type of data. We need to be thinking about students across time and with a range of assessments. How can we make this shift to looking at multiple sources of data?

1. Include Informal Assessments in the School’s Assessment Plan

We hear from teachers again and again that conferring notes, running records, reading response journals, etc. are not viewed as data in their school. This is a concern. Marie Clay reminds us in her book Reading Recovery: A Guidebook for Teachers in Training, “The one closest to the classroom experience is in a unique position to see and communicate a reliable and valid instructional perspective of the child.” A student’s performance in the classroom every day cannot be removed from the educational decisions we make. It is important to see how a child performs a skill in different situations and for varied purposes, for example demonstrating comprehension skills on a state standard test vs. demonstrating comprehension skills in the notes kept in a reader response journal. Each type of data gives us a different window into a student’s ability to express his/her understanding of text.

2. Use More Than One Type of Assessment When Analyzing Data

Many schools have set times for teachers to meet in teams or in grade levels to analyze assessment data. These meetings either occur monthly or during the school’s assessment cycle months. When we facilitate these meetings, we ask teachers to bring multiple types of assessment data. In one district, a group of teachers met to discuss the recent results from the DRA. We asked them to bring their DRA results as well as conferring notes from independent reading and students’ book logs. We use protocols to analyze data, and these protocols have teachers look at multiple data points to build theories around students’ strengths and areas to improve.

The DRA was used to determine how the students used strategies to decode unfamiliar words and retell the story. Analyzing conferring notes and book logs provides additional information about a student’s stamina; book choice, interests, and areas of instructional focus across weeks. One teacher took interest in a group of students who performed well above grade level on the DRA, but after analyzing their book logs noted that they were not reading very many books during independent reading. Based on the DRA, these particular students should have been able to read more books than were reflected in their logs and conferring notes. This teacher planned some small groups around stamina and setting goals with these students. Looking at multiple data points provided a deeper understanding of what was happening.

3. Value All Assessments

Some schools have multiple assessments, but only value some of them. When this happens, teachers overemphasize the importance of these assessments and often begin to base their instruction solely on them. Students should not be spending months learning how to perform well on a particular assessment. We should base our instructional decisions on all of the assessments that are administered, without basing judgment excessively on one particular assessment. Mike Schmoker reports, “In many schools, data-based reform has morphed into an unintended obstacle to both effective instruction and an intellectually rich, forward-looking education.” (Educational Leadership, 2009) We too have witnessed schools spending three months preparing for “the test” and two weeks taking “the test.” That is more than one third of the academic year. Schools that use informal and interim assessments as well as a state test to provide information about the authentic use of strategies allow students to experience a rich curriculum and be well prepared for “the test.”

4. Use Data to Answer Authentic Questions

When teachers use data to think about real questions they have about a particular student or a certain strategy they are using, they are more likely to use multiple data points. When you know what it is you are looking for in the data, you are more likely to keep digging deeper to find patterns or test theories you may have about a student. Authentic questions typically cannot be answered with one assessment. We need to look at students over time to help us understand why they are having difficulty with a particular strategy or skill. One school examined the state test score and noticed their students did not perform as well as they would have liked on the open-ended responses to reading selections. While the score was low, it did not tell them why the students did poorly. The teachers generated several hypotheses about why the students did not perform well:

1. They do not understand how to infer;

2. They do not understand how to communicate their thinking in writing; and

3. They do not have the stamina to read the selection and write their answers.

The teachers then went to other sources of data to confirm or refute their hypotheses. When they looked at how the students performed on a different standardized test, they noted the students did well on multiple choice questions that targeted inferring as a skill. Next, they looked at the students reading response journals and their writers’ notebooks and decided stamina in writing did not seem to be an issue for the majority of the class. As they looked more closely at the entries in the students’ reading response journals, they began to notice that they recorded their thinking in very general language and did not support their thinking with specific evidence from the text.

The state test requires that students cite evidence from the text in the open response answers. After looking at multiple data sources, these teachers had a specific area on which to focus their instruction – using evidence in the text to support inferences. They then set out to plan lessons to teach students how to do this during interactive read aloud and literature circles.

5. Look at Data Across Time Intervals

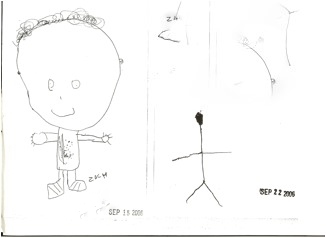

If you look closely at the dates on these self-portraits . . . this page illustrates quickly whywe do not want to make an assumption about a student based on one data point.

If we were only to look at Seth’s self portrait from September 22, we would have real concerns about his fine motor abilities. Once you look at the data over time, however, you begin to look at Seth differently. One week prior, he was quite capable of drawing a detailed self portrait. We could take a look at other drawing samples from Seth and maybe talk with him about his drawing to get better insights as to why he drew his self portrait differently on September 22. When we look at data, we always want to look at change over time to understand how a student is performing in relation to him/herself rather than just one point in time.

With the current relentless push for more assessments, we need to make sure we are using assessments to help us understand the students we are teaching and to lift the quality of our instruction. There is no one assessment that can give us all the information we need to make good educational decisions. Formal, informal, interim, formative and summative assessments need to be balanced to provide teachers with a full profile of a student. If we depend too much on one measure, we risk the danger of making judgments without truly understanding why a student is struggling and worse yet, basing our pedagogy on getting students to perform well on one test.