As our district’s writing coordinator, I love working with children who are struggling to write. Yes, I love to work with the gushing writers, but there’s something really rewarding about convincing a nonbeliever that their stories are so important that there’s no option other than to write them down. Who cares how to spell the words?

Below are options that I’ve tried in many classrooms and that teachers have easily duplicated on their own. These are the techniques that have worked many times with those writers who just. won’t. write.

-

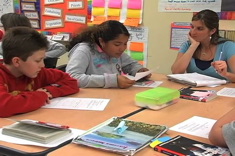

Pay attention to how you make your striving writers feel. We all remember how people make us feel more than we remember what they say. If somehow you can make them feel like a writer, like a person with stories that matter, like a person who uses words to affect your feelings and reactions, you’ll have a better chance of getting that striver to write. If you let on that you can’t read their writing, or if you correct their spelling, letter formation, or overall illegibility, they’re going to feel incompetent. Shutting down often feels better than incompetence.

-

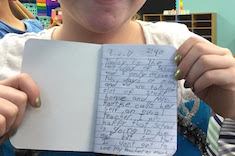

Have special pens. I can’t tell you how many times a nonwriter has become a writer because I’ve pulled out a super-special Flair pen or offered them a choice of colors. Sometimes I warn these writers that the pen they’ve selected writes really, really fast. Sometimes, a gimmick is all it takes.

-

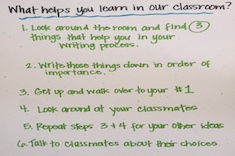

Gimmicks don’t always work, so I have a few go-to tools in my coaching bag. One of my tools is a folder of paper choices. I have a variety of paper choices with varying picture-box sizes and varying lines. Some paper choices have only one line and a large space for a picture. Others have several lines and a small picture box. I also have packets of three pages, so that I can nudge writers to write across pages and think in terms of beginning, middle, and end. The number of lines sends a subtle but powerful message to writers. I want my writers to think, Yes, I can fill up those pages! I don’t want them to think, There’s no way I can write that much.

-

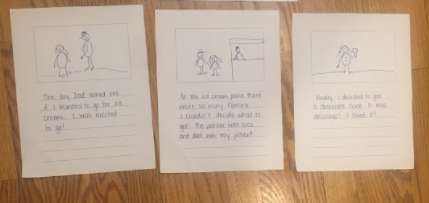

Showing students what the work looks like on a continuum is powerful, but for striving writers, it’s especially useful to have examples of the work well below what they probably can do independently. Maybe this is because they’ve had so much experience with not being successful that they don’t even try to write what they are capable of writing. In any case, one of the tools I use a lot with children who are hesitant to get going is a continuum going from kindergarten up through the end of first grade. My model story is about going for an ice cream cone with my father. I have the kindergarten version that contains only labels, followed by a version with a single sentence and another version with a few sentences. I have a fourth version of the same story that spans three pages.

I ask students to think about what version they think their story could be like, and many times, they choose the option I’d hope they would. If they choose a lower option, I’m okay with that—sometimes I choose an easier exercise class on a given day. What I’ve seen happen over and over again is that they experience success and satisfaction, and then they progress.

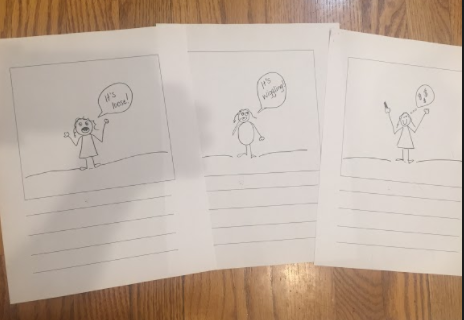

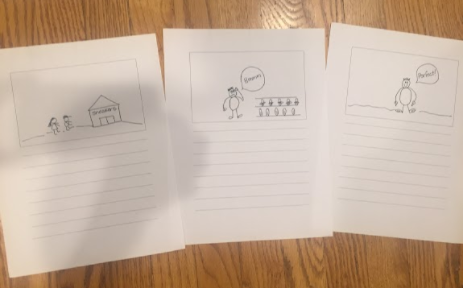

5. One last tool I have in my bag is one I try not to take out too often: the story jump-starter. But it comes in handy every now and then, and it’s for those students who will NOT or can NOT think of an idea. Any suggestion I have gets a no, any lesson I offer is a fail, any brainstorming session comes to a dead end. I have several three-page booklets with pictures already drawn that tell a story most children have experienced. For example, I have made one about losing a tooth.

Almost all of them can relate to having a loose tooth that falls out. I also have one about picking out perfect sneakers.

This one tends to entice boys. I have a few others, including ones about not being able to think of a story, sliding down the playground slide, skinning a knee, and losing my homework. When a child is really stuck, I offer a choice of two or three of these templates—not all of them—and have them write the story to go along with the pictures. As you can tell from the pictures, I vary the number of lines that I offer, and sometimes the options I offer children have more to do with the number of lines than the topic.

Originally, I created several choices so that I could give the same student another and another until they could think of their own idea. What I have found is that I’ve never had to give a child more than two of these, and most children need only one before they are up and running with their own ideas and story topics.

Oftentimes, teachers ask for the samples and for the continua, and sometimes, they even create their own demonstration texts. I am always on a quest to empower writers, and one of these ideas almost always gets even the most resistant writer to start.