The writing process is simple and complex all rolled into one ball. There are a handful of phases and as many ways to execute each step as there are writers on the globe. This truth makes it tricky to balance both the steps of the writing process and individual needs when helping students discover the writing process and what it means for them.

The writing process is simple and complex all rolled into one ball. There are a handful of phases and as many ways to execute each step as there are writers on the globe. This truth makes it tricky to balance both the steps of the writing process and individual needs when helping students discover the writing process and what it means for them.

One of the things I struggled with in writing workshop was how to allow for students to move at different paces. Inevitably there are some writers in the room who plan in 60 seconds and others who don’t have a plan after 60 minutes. There are some who can crank out a draft in one day and others who need several days for one draft. Some writers form a complete plan, whereas others draft a little, then plan a little. It is easy to become overwhelmed by the diversity of the writers in a classroom.

The more I write, the more I realize I don’t always develop a plan first, nor do I revise everything I draft. My notebook is a tool I use throughout the process, not only during “prewriting.”

The more I considered the ways I expected students to work through the writing process in writing workshop, the more I realized many of my expectations contradicted what I do as a writer. My writing process is not lockstep. I do not march through each step and neatly develop perfect writing. Anyone who says otherwise is teaching writing without writing themselves. It’s unfair to send students the message that writing works like this.

Writing is a messy business, yet it is predictable as well. Here is where my quest began to help a classroom full of diverse writers develop, sustain, and refine their own writing processes.

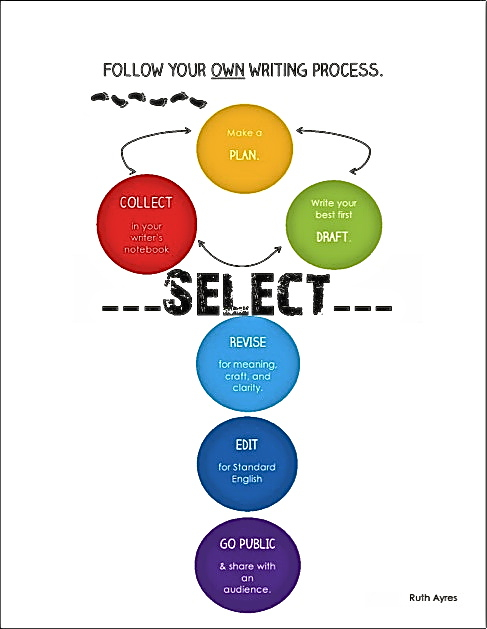

Collect

To begin, I changed the way I talked about prewriting. This term was confusing to me. Did it mean to make a plan, or was it more about jotting ideas? Was sketching prewriting? What if I needed to jot a list while I was in the middle of my draft? Was it still called prewriting? What about the stuff I wrote in my notebook when I didn’t really have an idea for a project, but I wanted to keep it just in case I ever needed it? Was this still prewriting? I found students struggled with the term as well. So I changed it to collecting.

Writers collect in their notebooks. They collect materials around a single idea when beginning a project. They also collect possibilities for revision. They collect ideas for future projects. And they collect bits and pieces of life that may (or may not) have significance. Collection can happen throughout the writing process and encompasses more than prewriting.

Plan

Writers also plan. For me, this is a different step in the writing process from collecting. I still use my notebook to capture a plan, but it is for a specific writing project. Planning is thinking through the parts of a writing project. In addition to planning the parts, I also plan for research, as well as the timeline I foresee for completing the project.

Draft

Writers write their best first draft. This is not a sloppy copy. A best first draft is when writers intentionally mold their words, developing meaning through craft and conventions.

Circular, Not Linear

Instead of these three phases creating a linear path, I see them as a circle. Writers enter writing projects at any one of these three phases. You might begin by collecting writing around an idea. However, sometimes a writer makes a plan first, and other times (as is the case for this article), a writer could begin drafting first. Writers can enter into the writing process at any of these three points.

Because they form a circle, one phase doesn’t supersede another. They are all important, and writers use all three of these initial phases of the writing process. Another advantage to thinking through the writing process in this way is that when students say, “I’m done!” we can respond, “Great! Start another project.”

Then they begin their work again, starting with collecting or planning or drafting an entirely new project. This gives students the chance to practice, as well as allowing everyone to work through the writing process at their own pace. During this time, minilessons focus on the nuances of the genre as well as craft techniques. Sometimes there might be a convention lesson to support students in writing their best first drafts, or in adding voice to their writing through conventions.

By expecting students to write at least two different best first drafts for a unit of study, we provide them with ample opportunities to practice. Before, when I shared a linear writing process with students, they wrote one draft, revised, edited, and said, “I’m done!” It was difficult to get them to keep writing, because they felt they had accomplished the task I had set before them.

Selection

After students have written more than one best first draft (this means they’ve drafted two or more entirely different projects—not rewritten the same draft two times), it is time to move into selection. This is a truth for all writers: we don’t publish everything we write. There are many articles I’ve written that will stay in a drafts folder on my computer. They aren’t worth my time to revise, edit, and publish (and they definitely aren’t worth your time to read). They are, and will always be, drafts. I’m done with them, so to speak. However, it is also truth that from time to time writers share our work with others.

It is important to teach students how to select a draft worthy of sharing with an audience. What project has the most potential? What can you see yourself spending lots of time rereading and reworking? What can’t you wait to share with others? This is the project worth your effort to prepare for publication.

Revise

When preparing a draft for publication, it is important to revise for meaning. Writers typically do four things when revising: delete, add, restructure, or rewrite. The commonality is that everything we do in revision is about strengthening meaning. We can delete unnecessary parts and add new parts. We can restructure by moving parts around or combining sentences. Sometimes we simply try again. Sometimes it is best to rewrite a part, not to improve penmanship, but to strengthen meaning. This is hard work, which is why we select a draft that is worthy of our attention.

Edit

This step of the writing process is about Standard English. It is important to make writing as conventional as possible. Conventions hold power, and when writing is going to go into the world, it is best if it meets the rules of Standard English. At the same time, writing workshop is first about teaching writers, not about perfect conventions. If the writer is five, then the writing should reflect their age and development. This step in the writing process is about getting as close to conventional as possible for young writers.

Go Public

Finally, writers share their writing with an audience. Writing for others makes the hard work of revision and editing worthwhile. Make certain students have audiences both inside and outside the classroom walls. Provide students with the opportunity to go global with their words. Allowing them to share via social networking sites helps students realize that their words matter both inside the classroom and outside.

Forever Writers

Mem Fox says, “I wish we could create powerful writers forever, instead of indifferent writers for school.” One way to do this is to help students find a meaningful writing process. An approach like this provides students enough structure to be efficient, and enough choice to be effective. It takes a little structure and a little choice to make the writing process work for students.