I’ve been reading Street Data by Shane Safir and Jamila Dugan, as well as listening to the accompanying podcast. This book and podcast are about gathering and using the kind of data that truly measures equity and learning. One idea that keeps popping up is the idea of slowing down. Slowing down to really listen. Slowing down to reflect. Slowing down to “see the whole learner.” This is something that has resonated deeply, because I see educators literally running around, trying to do their best in a system that is about speeding up.

When everyone is talking about acceleration and catching kids up for “learning loss,” slowing down seems counterintuitive, maybe even irresponsible. As educators we’re told we need to work with urgency, because the kids don’t have time to waste. It’s true kids don’t have time to waste. But when I reflect on some of the teaching practices I engaged in when I was working with urgency—relying on extrinsic rewards to manage behavior, over-scaffolding tasks so kids would seem successful, teaching to the dreaded state test—I realize that none of them made long-lasting impacts on my students’ learning. Slowing down isn’t really about taking more time to do things, but about taking the time to prioritize and focus on how we spend our energy and time.

In just about every school I’ve been supporting this year, teachers are working under tremendous pressure to get kids ready for test after test after test, not just in the spring, but all year long. Many report that they don’t have time to do things like give kids choice in their writing or allow them to read their independent books because they are teaching kids how to write for the test or read passages and answer questions that look like those they’ll find on the test. However, what they’re also finding is that kids aren’t motivated to do any of the work, and neither students nor teachers are finding joy in teaching and learning.

So when we intentionally slow down, what areas of our teaching do we want to prioritize?

Voice and Choice in Writing

Last week I worked with a group of teachers who are under the same testing pressures as everyone else, maybe even more so, because they are under greater district scrutiny this year. Just before the pandemic, we started working together to implement the writing workshop structure. However, once instruction went online, it was difficult to continue the momentum, and once school was reopened, teachers felt pressured to “catch kids up.” The writing process and workshop was dropped.

However, we were able to restart that work again last week, and what we saw was the joy of slowing down! Instead of planning a unit that would focus on the state test coming in spring, we prioritized student voice and choice. In one class, third graders started writing reviews, and in the fourth- and fifth-grade classes, writers began information books on personal expertise topics. In each class, every student tried out the writing, with most students excited and eager to do the work. Even students who had been reluctant gave it a go. And not once did we hear a kid ask, “How much do we have to write?” It was clear that all the test prep wasn’t really helping students. How could we teach them how to write clearly if they weren’t writing at all?

Joyful Reading Experiences

In another school I support, our focus is on planning and implementing interactive read alouds. The primary teachers I work with are required to administer an assessment that relies heavily on kids reading nonsense words and very minimal comprehension skills. In a well-intentioned effort to increase those scores, a great amount of their language arts block is taken up by isolated phonics work. (This is not an argument about phonics! Kids need it, but research shows that the amount of time spent on explicit phonics instruction should be limited to be effective.) What has been pushed to the side are shared reading and read alouds, two practices that not only build readers’ skills but are also joyful.

When teachers and I went into classrooms to try some new read aloud work, kids were smiling, they were engaging with the text, they were engaging with each other. We realized that the thinking work we were asking kids to do had been missing from the day but was sorely needed.

Actual Reading

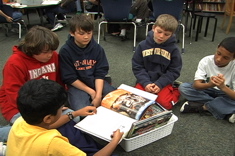

In addition to community reading experiences, kids need more time to actually… read. So much of the day gets taken up with reading-adjacent tasks. Read this passage and annotate it for the main idea and details. Read this passage and answer these comprehension questions. Read this passage and write a response. The amount of time reading is a much smaller percentage than the time it takes to complete these activities. Also, the reading material itself is assigned with little or no student choice.

The International Literacy Association makes the importance of reading time clear: “The more students read, the better their background knowledge, comprehension, fluency, vocabulary, self-efficacy as readers, and attitudes toward reading for pleasure” (2018). Time spent reading, especially self-selected reading material, not only brings more joy to students but will also increase their skills as readers.

Slowing down in a time when the message is go, go, go can help us refocus on the practices that will have a greater effect on students’ learning, bring more pleasure to all of our work, and help students make gains on their dreaded tests.