Peer-to-peer feedback is something we value in our classroom. We expect that the feedback that peers give to one another can lead to meaningful revision, just like the feedback we strive to give our students. This is the expectation that guides the work that we do in teaching our students how to give feedback to one another.

We know that your schedules are tight and that to find the time to let students give feedback to one another, you need to find the value in this practice. It seems that what they say to each other can sometimes be cursory and nonspecific. How can telling a peer that they like his writing help him become a better writer? We feel your pain, and starting out the school year, we often hear what we’ll call “agreeable talk.” Agreeable talk might sound like this:

Partner reads writing while partner B nods and makes eye contact to show good listening skills.

Partner B: “I like your story. It sounds good.”

Partner A: “Thanks.”

This kind of agreeable talk may give a temporary feeling of pride to the writer that her work was appreciated, but it doesn’t let her know what exactly made it good that she could try to repeat or what her next step could be to improve.

Now, don’t get us wrong; we’re not trying to stifle our students’ voices and feed them words that don’t belong to them. We want feedback that kids give to be authentic and come from the heart. But for the feedback to be effective and purposeful (and time in a classroom is too valuable to be spent on anything that feels ineffective or purposeless!), kids need to recognize the specific elements of writing that make it stronger. Specific feedback leads to possible revision strategies for the current piece of writing and new writing tools for future pieces.

Now imagine this conversation in a fourth-grade peer conference:

Partner A reads a section of an informational article that describes how fast cheetahs are. Partner B nods and makes eye contact to shows he’s listening.

Partner B: “Wow, I learned a lot. I like how you used a comparison to show how fast a cheetah was when you compared a cheetah running to a moving car. That really helped me picture in my mind just how fast a cheetah is. I wonder if you could try using comparisons in other parts of your article.”

Partner A: “Thanks. I like that part too. Can you help me find another part where I could try that?”

Partners A and B look over another section, searching for a part where a comparison could work.

Feedback that was actionable, meaningful, and still sounded like it came from the mouth of a fourth grader. How do we get our kids to do that?

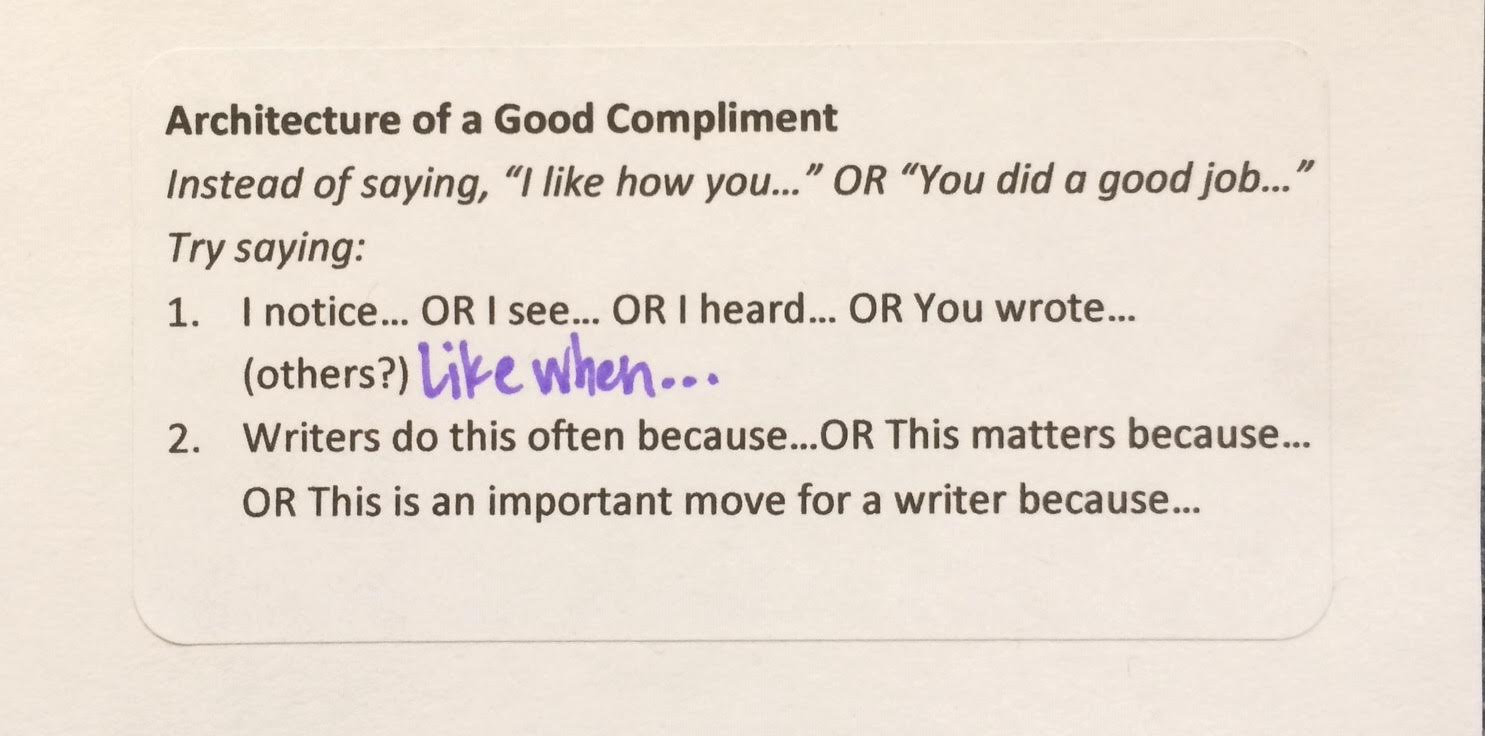

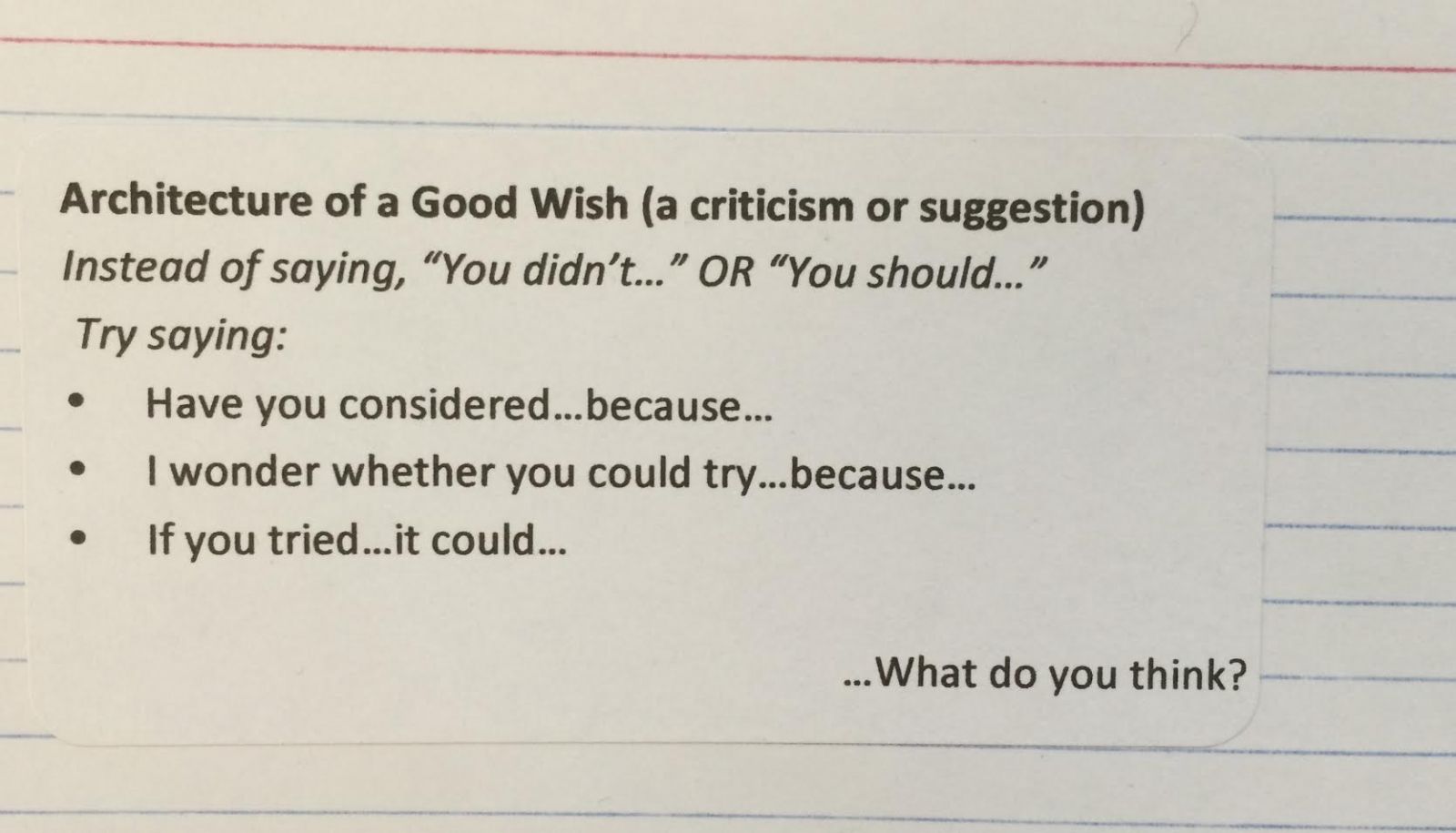

After listening to agreeable talk in our classroom, we decided that although we wanted kids’ conversation to come from an authentic and natural place, they needed guidance to help them get started. So we teach kids how to use this scaffold very early in the school year:

This card, which is made by printing the text on labels and then sticking the labels to the two sides of an index card, helps our students see the value and purpose of giving peers feedback and breaks down what they’re doing into steps.

This card is a scaffold and, like all scaffolds, temporary. Students will use the card for as long as they need it, and once they’ve internalized these steps, you won’t see the card come out as much or at all. (Our students keep this card and others that are given to them during minilessons, conferences, or small groups in a library pocket in the back of their writer’s notebook so they always have access to them during writing.) They may paraphrase the language, but they’ve internalized the steps so they won’t need the card. This happens at different times for different students, and it’s what we expect to happen.

This type of feedback is good for the writer receiving the feedback and good for the partner giving the feedback. The process of looking critically at writing and naming what’s there as well as what might not be there makes both partners more likely to begin doing that work in their own writing.