I have always done a study of nonfiction as part of our year in writing workshop. This study of nonfiction writing seems critical for students in the upper elementary grades, because we know that they will need good nonfiction writing skills throughout their schooling and lives. In our district, writing literary nonfiction is a focus unit for our fourth graders.

As I began to plan my nonfiction unit, I fell right back into a research emphasis in the planning — my students would choose a topic, research, collaborate with peers, and write. However, the more I thought about it, the more I realized that when I did this unit, the focus was more on research than on nonfiction writing skills that I knew my students would need. Research skills are essential — but do they need to be the focus of every nonfiction unit?

I thought about nonfiction writing in the real world — most people write about what they know well. I never write about whales — I usually choose topics that I already know a great deal about. Asking my kids to research something related to the required science or social studies content seemed a mismatch for the writing skills I wanted them to gain. If they focused on the writing, and not learning new information, my theory is that their nonfiction writing would improve greatly.

I thought about my students’ writing, and asked myself what my goals were for them. Focus is a big issue in student writing. They can stay on topic, but there is little order to sentences or paragraphs. A student might write a story about their birthday party, but it would be everything from how they made the cake to who was invited. Focusing their writing would be a key skill to learn that could be applied across multiple genres. I also saw several great strategies in their writing notebooks — lively language, use of similes, excellent leads, and strong verbs — that I wanted them to transfer to their nonfiction writing.

When we have focused on nonfiction writing in the past, students seem to be drawn to the format and layout. They use all that they know about nonfiction text features to create nonfiction text with headings and captions. Using a variety of text features well can be important in nonfiction, but it isn’t necessarily the crucial element in strong nonfiction writing. Often when students focus on the visual nature of the nonfiction, they don’t pay enough attention to the craft of the writing. Nonfiction writers need to do both.

When I reflected on what was stifling students’ nonfiction writing, I realized that I didn’t give them time to play with nonfiction writing in their writers’ notebooks. It was hard to write nonfiction and to play with the craft before we researched and learned about a topic. I decided to let kids play with nonfiction writing, learning about it as they wrote about things they know well.

Starting Points for Redefining a Nonfiction Unit

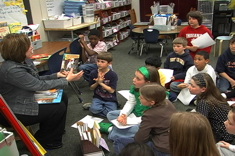

Because one of my goals was promoting better focus in writing, we started out studying the writing of authors as they described people. We were able to look at the craft of writing in fiction and nonfiction. We learned the many ways that authors write about people, and we also analyzed the important things that writers wanted us to know. We read picture book biographies like Martin’s Big Words by Doreen Rappaport. We also looked at sports star blurbs in current issues of Sports Illustrated for Kids

, and the poem “Not Enough Emilys” from Jean Little’s Hey World, Here I Am

.

After discovering many ways that authors describe people, we played with these techniques in our notebooks, writing about the people we knew well in our lives. We thought about the important things we wanted our audience to provide focus for the writing. I was amazed at how much writing improved when students could write nonfiction about familiar people.

Moving On with More Models

As we moved on, we brainstormed other familiar nonfiction topics. I modeled my own list for them, which included Guatemala, adoption, boot camp, books, teaching, Italian traditions, and being a mom. Students had fun generating and sharing their lists. We then moved on, studying some high quality nonfiction writing while we played with the nonfiction writing in our notebooks.

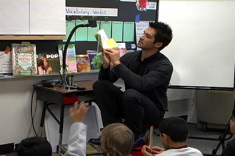

Together we discovered terrific mentor texts to learn from. Similar to the way we looked for authors who wrote about people, we each collected samples of nonfiction writing — things we would like to try in our own writing. I shared the books that had become mentor texts for me, including It’s a Butterfly’s Life by Irene Kelly and A Seed is Sleepy

by Dianna Hutts Aston. Both of these books use language in surprising ways to help the reader learn new things about the topics. Students then found their own mentor texts and tried some writing in their notebooks, playing with topics they knew well.

This study was not that much different from units on nonfiction writing that I have done in the past. Much of the difference was in my mindset. I focused my energies on working on nonfiction writing skills rather than on research. The transfer of skills to other research topics will be more natural for kids now. They were given the time to experiment in their notebooks and discover more about themselves as writers, before they moved on to content-related topics where the content was so new. I am not sure where the rest of the unit will go, but I know that my own change in focus – from research to the craft of nonfiction writing — was key to the growth my students showed.