It was writing workshop time on a mid-October Wednesday, and the buzz of four children chattering in excited voices was a dead giveaway that something wonderful was about to happen. A team of kids put the finishing touches on their part of our weekly class newsletter at a nearby table. For the prior two days, the kids had been puzzling their way through a challenging writing task. They wanted to write a special page about our school's custodian. From across the room, I could see that while they worked in a cooperative and productive manner, the kids were stuck and struggling with the process.

I watched them from afar, fighting the urge that all classroom teachers wrestle with each day. I stayed away from them, and stopped myself from joining this table of collaborating writers before they really need me. Because we care so much, teachers often help too much or we want to help too soon. The dilemma is that when we get involved before children have a chance to work through a challenge and bring a solution to the situation, we take away learning opportunities that are more powerful than any grade level's standard. Standing still is so hard when teachers are constantly focused on moving forward.

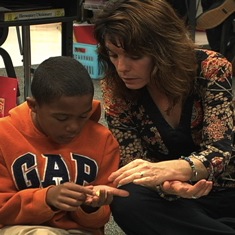

And so I waited. I told myself that I would not get up from my conferring table and talk to the team unless there was a fire drill, a medical emergency, or my biggest hope — a call from the four writers hard at work on our newsletter. As I wrapped up one and then a second writing conference, I realized that my brain had drifted during my 1:1 conferences, distracted by the nearby table of collaborating writers. I'd been working like an undercover detective, secretly watching the writers rereading their edition of the weekly newsletter. I promised myself that I would sit, wait, and not move until I got the call from this writing group. What a challenge.

Finally, the moment came.

I saw all four heads lift and turn in my direction and then they looked at one another.

"We are ready," announced Ayla to her peers. I made eye contact, ready for their call to meet. They shuffled papers and I wiggled in my chair. "She is free right now . . . let's call Mrs. Smith over."

"Mrs. Smith? . . ." Ayla called.

"Yes," I said casually as I glided across the room (fighting my urge to rush over). "How is the newsletter coming along? Is it ready for a class review?"

"It is much better since we started listening to each other's ideas," Cole confessed.

As I listened to Cole, I realized our weekly newsletter has also become much better since we've integrated the process into our writing workshop. The newsletter has become a vehicle for building relationships across the school community, for honing nonfiction reading and writing skills, and for helping students learn to negotiate with each other.

The Nuts and Bolts of Our Weekly Newsletter

Each week, a team of students is asked to contribute to our classroom newsletter, a publication shared in hard copy and e-copy formats with our families and community members. The team was responsible for interviewing our beloved custodian and creating a "Paparazzi Page," a weekly installment that highlights important support staff in our building. Knowing members of the school community is such a positive way to build lasting support in a school.

The team is responsible for helping me select newsletter topics and drafting selections for the publication. Monday through Wednesday, the team writes entries for our Friday newsletter. This gives the team time to gather information before writing their pieces. Students may need to interview staff members or classmates. They may also need to review our student handbook to explain important elements of our school day, such as why we have fire and tornado drills.

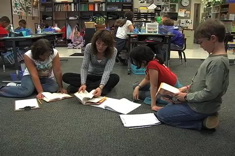

On Thursdays, our draft newsletter is presented to other students during our morning meeting, and the class helps to edit and revise any sections or provide constructive comments before it is copied and emailed to families. Working with a partner, each student reads and leaves comments on the draft during a quick ten-minute review session so the newsletter can be improved before publication.

On Friday morning, kids deliver hard copies of our newsletter to staff members in our building. If our principal, secretaries, custodian, and support teachers have time, messengers share at least one part of the newsletter, reading aloud to that key adult in our learning community. Sharing our classroom news attaches value to our "newspaper" as the kids call it, and builds the idea that short information pieces are just as important as longer nonfiction resources. The newsletter supports the idea that informational reading is valuable and fun at the same time, especially when it communicates school news or information about meaningful topics such as our learning community, projects, and the lives of classmates.

Friday afternoon finds students taking the publication one step further with a special review time. I pass out hard copies of the newsletter right before students prepare for dismissal. Students are asked to read the newsletter, reviewing it one more time, and they highlight at least one entry that they want to make sure that their parents read.

Printed newsletters are displayed in a clear plastic pocket outside our door so visitors, other students, and families can read the newsletters. Back copies are saved in a binder and shared with new students and visiting community members. The kids even read the latest newsletters and reread archived newsletters during indoor recess time when they want to talk about and remember events in our classroom.

Learning in the Midst: Back to the Workshop

Let's return to the group of students who were drafting the latest issue of the newsletter. Their interaction demonstrated to me how many skills students were using simultaneously.

"So tell me about how you started listening to one another," I said.

"We knew that we wanted our page to include an interview or a story and pictures of Mr. Rod since custodians are so important you know. And we wanted people to know and care about Mr. Rod," said Ayla as she was interrupted by a teammate.

"But our story was boring because it was a big list of facts that were smooshed together, so we decided to take the facts we got from our interview with Mr. Rod and use them in different ways." said Anna, finishing Ayla's idea.

"We noticed the problem right away when we read our first draft," explained Cole.

Ayla chimed back in the conversation. "I was in charge of pictures, right? I thought that each picture needed to show what Mr. Rod does and why he is important to us every day. I took great pictures but then after we put them in the newsletter, I realized that each picture was just sitting there and it needed to say and show something. Each photo needed a power word to show what his picture stood for. See this picture here? It is Mr. Rod fixing a table. Well, I decided that the picture needed the title of 'Problem Solver' and then it needed a caption to explain how Mr. Rod solves problems all day long."

Zach, a quiet writer until now, added, "We thought the titles and captions made Ayla's pictures so much better because her titles and captions really told the reader what she was trying to prove with her pictures."

"Tell me more about the fact box over here." I pointed to a sidebar composed of a title and a list of interesting facts about Mr. Rod.

Anna began the discussion. "Well, we used all of the information from our interview survey. When I started to write about Mr. Rod, some of the facts seemed important — the kind of information we needed to really know about him . . . but some of the ideas were just cool facts that you wanted to know but they seemed to just drag along in the paragraph."

"Remember last week when we talked about how nonfiction books are put together? You know the way helpful writers let you focus on important ideas and save the extra facts for side reading? Good writers have texts with big ideas — the important things we want to learn. They save the factoids for side thinking. You know, like that zebra page we looked at last week? Remember the writer explained zebras' color patterns and how they live in a herd for survival? Then, on the side of the page, the writer put a fact box listing the size, weight, life span and other super small facts about zebras. These were facts that might not make a big difference in understanding zebras' lives, but they were cool to know. The fact box had interesting facts, but not the most important ideas on the page."

Zach continued, "So we decided to use that writing plan. We think Mr. Rod is a great custodian because he does his job just like he is our dad when we are at school. He treats us like he is taking care of his family. So Anna wrote about how he has a family and he comes to school each day ready to show kids good ways to live and learn. He wants us to know what he thinks is important."

Anna added, "Zach made the fact box. We talked about how people are nosy and like factoids too."

"We wanted kids to know fun facts about Mr. Rod, like his birthday, favorite sports teams, favorite foods and snacks . . . you know the fun stuff. So I wrote the 'Big Idea Paragraph' and Zach made the fact box on the side with cool facts."

I looked over at Cole, who was patiently waiting his turn.

"I wrote about Mr. Rod's favorite books. Actually, I listed the books he liked to share with his kids when they were growing up and I also listed the sports magazines he reads for fun because he loves all kinds of sports. Since the class decided that our school interviews needed to include book stuff, we wanted to give kids different kinds of reading ideas." Cole said, with a proud voice.

"This was really fun." said Ayla. "We hope the class likes our part of the newsletter."

"It was kind of hard, but we worked it out once we realized that our first draft was super boring . . ." added Anna.

"And we did this all by ourselves. But now we need you to edit this and maybe help us with words that just don't sound right before the class sees it on Thursday," Cole requested.

"Do you have a minute?" asked Zach.

"Of course," I said, settling down in a chair, while four kids hovered over my shoulder, waiting with pride and a sense of accomplishment sparkling around them.

Lesson learned: Know when to sit still and wait, and know when it is time to move ahead or get involved.

Reflections on the Newsletter

When I had quiet time after school, I reflected on why student involvement in classroom newsletters and team writing projects were such powerful learning experience for all students in our classroom. I thought about why our news-writing teams had become a critical foundational routine and ritual in our nonfiction reading and writing program. Why was a student-created newsletter valued? How did I pull this off week after week?

Co-writing a classroom newsletter with students is not an unusual practice in elementary classrooms. Many teachers and students collaborate and write weekly newsletters that are published and shared with families and community members. When the newsletter production, editing, review process, and sharing experiences are presented with students' information reading and writing lives in mind, the newsletter provides powerful and intentional curricular connections when you consider all of its possibilities.

Previewing and highlighting the newsletter is important for several reasons. I want the newsletters to do more than present information. I want kids to share their excitement about what we are doing at school and transfer that enthusiasm to their parents. When kids are a part of the writing process, newsletters become more than crumpled pages at the bottom of backpack or quick emails sent to their parents. Writing, previewing, and marking the newsletter insures that kids will encourage parents to take time to read them, because our learning community is invested in these newsletters.

Sharing the writing and reporting of classroom information has not only improved family awareness of weekly life in our classroom, but the newsletter process helps students realize how fun and important informational reading and writing can be. The routine of a weekly newsletter is already in place in a majority of classrooms; recognizing the maximum potential of our newsletters can strengthen a learning community while supporting the attitude that reading and writing informational resources is practical, valuable, and fun.