My state and district standards require that seventh grade students should be able to write persuasively. Traditionally, teachers meet this standard by assigning a speech or a paper, and I found myself stuck when trying to think of anything else to do. Then one fall, a small group of Ron Paul supporters appeared with a banner and some pamphlets across the street from my classroom. My students and I stared out at them, before I closed the shades to continue with class.

As I watched the activists, I found myself wondering how many times during the past few months people had tried to hand me some kind of written material as I walked down the street. There were too many to count. I realized that despite the amount of information available on the Internet, politicians (and businesses) still rely on good old-fashioned pamphlets to get out their message. And, with a practicality that would have made those activists proud, I realized how cheap and easy it would be to reproduce this idea in the classroom.

Prewriting

To begin a persuasive pamphlet unit, I ask my students about election mail their parents receive at home or material that they get handed in the street. This sparks a lively conversation, in which seventh graders eagerly share their parents’ annoyance with the amount of mail they’d been receiving. I assign them to bring that mail in so we could look at it. Students and parents are only too happy to comply. For a few days, we dedicate the first part of each class period to sharing mail that has been brought in. As we do this, we keep a class list of the persuasive techniques that we see used in the mail. The mail is displayed on the bulletin board so we can be reminded of it. Students also learn about fact and opinion, and practice distinguishing between the two. (As a side note, in non-election years I start off a persuasive pamphlet unit by having students bring in business advertisements and sharing pamphlets I’ve accumulated.)

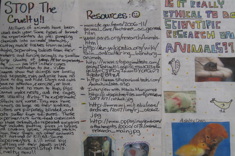

Once students are familiar with persuasive techniques, they begin work on their own topics. First, they brainstorm and share lists of things they have strong opinions on. By sharing brainstorm lists with each other, every student is able to come up with a topic of interest. I try to give students complete freedom in their topic choice, as long as it can be supported by facts. Favorite topics have included why scooters are better than skateboards, why animal testing is wrong, and why a certain video game system is the best.

Research

Students conduct research for their topics in a variety of ways. I try to schedule a day or two of computer time to research topics such as animal testing. I also encourage students to find experts in the classroom. Many of the political pamphlets we’ve analyzed contain quotes, and I ask students to gather some of their own. The boy who rides his scooter all the time or the girl who owns all the Nintendo Wii games suddenly become sought-after celebrities. Sometimes students create a chart or graph based on their classroom interviews, proving that their opinion is supported by the majority of first-period students. Students also write persuasive narratives about their own or others’ experiences, as this is another technique politicians love to use.

Writing

“Writing” a pamphlet actually involves equal amounts of writing and design. This is where the mail that students have brought in really comes in handy. We review persuasive techniques we’ve seen and also examine designs before students begin to create their pamphlet. Students sketch out a rough draft on notebook paper, before using white computer paper to make their pamphlets. I remind students that the paper is fairly thin, so they should avoid sharpies and stick to colored pencils. Construction paper could also be used. Most students prefer to create a pamphlet on paper that has been folded in thirds; however, some students with larger handwriting prefer to fold their paper in half.

Since pamphlets do not require as much writing as other projects, I’ve found they are really accessible for students who are still learning revision techniques. We peer edit for spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. A minilesson on how to punctuate quotations fits really well in this unit.

Persuasive pamphlets are the first time I teach my seventh graders about sources. We do not cite them in a formal Modern Language Association (MLA) format, as politicians usually do not (however, teachers may choose to introduce MLA in this unit). I do require students to use a certain number of sources, and to list them somewhere in the pamphlet (they usually choose a back panel). Students enjoy learning the correct spelling of each other’s names, and pamphlets also present the opportunity for minilessons on assessing Internet sources.

Publication

When the pamphlets are done, students share them with each other. Since classroom management is always an issue in middle school, I do this by dividing the class into halves or thirds, depending on the size. Each group of students forms a circle with their chairs. I use a stopwatch projected from the internet (www.online-stopwatch.com) to give students about two minutes to examine each pamphlet. Once their time is up, they pass the pamphlets clockwise around the circle. Although it sounds forced, the class is usually silently absorbed in reading the pamphlets, chatting only when I say it’s time to pass the pamphlet on. I haven’t seen this level of absorption when I ask them to walk around the room to look at each other’s work.

When students have looked at all the pamphlets in their group, I then ask them to share favorite pamphlets with the class. I ask students to tell what the author did well. The period closes with a short written evaluation, focusing on the following questions:

- What was the opinion in your pamphlet? What was the best fact you found to support your opinion?

- What persuasive techniques did you use when writing

your pamphlet?

- What was one of your favorite pamphlets that a classmate wrote? What persuasive techniques did they use to create their pamphlet?

Once I’ve graded the pamphlets, they take the place of the professional persuasive items that had previously been displayed. Students love looking at each other’s pamphlets.

Possible Extensions

In classrooms with more access to technology, pamphlets could be printed using computer software, which would allow multiple copies of them to be distributed. Other teachers might be able to come up with ideas as to how to share pamphlets outside the classroom. Pamphlets also bring up tough and relevant questions on how research can be manipulated, and this is an interesting conversation to have with students. The unit could be infused or combined with a Media Literacy unit. I will certainly continue to develop the persuasive pamphlets unit.

My students often tell me that persuasive pamphlets are one of their favorite units. For students who struggle with writing, this is a way to build confidence. Since pamphlets are divided into panels, organization is fairly intuitive, and students who struggle with paragraphs later in the year can be reminded how they grouped pamphlet information. Finally, persuasive pamphlets are a somewhat selfish thing for me: I have bad memories of hours spent in the library crafting five-paragraph essays on a persuasive topic. In exploring pamphlets with my students, I’ve begun to see what an interesting genre persuasive writing can be. The media for expressing opinions are nearly endless, extending far beyond the classroom essays and libraries.