“You’re not stepping into the ball,” Kurt said as he hit another tennis ball my way.

A hundred other directions marched through my brain as I concentrated on moving my feet, watching the ball, taking my arm back but not too far, keeping the racket head up, making sure the ball hit the center of the strings . . .

“Just step into the ball,” he said again. “Stop thinking about so much.”

I shut my brain down and followed his direction. Wham!

“Way better,” Kurt said as the ball whizzed over the net. “Just keep thinking about stepping in.”

From Tennis to Conventions

Sometimes practicing tennis reminds me of learning conventions. If there are too many things to work on without having the muscle memory of at least some of them, then it’s tough to hit a great forehand. Likewise, when students are learning to write, they are juggling many new skills all at once. Before we even throw punctuation and spelling into the mix, a third-grade narrative writer is working on the following:

- Letter formation

- Neatness

- Remembering their story

- Following a plan

- Including some description, action, and talk

- Bringing characters to life

- Using transition words

- Working toward an ending

And this lists consists only of items that have to do with the process of writing—it doesn’t include any social interactions or distractions that could be happening over the course of an independent writing session! My point? These students are juggling a lot!

I’d love to have a dollar for every time a teacher has said to me, “I’ve taught them to use end punctuation [or quotation marks, or comma usage, or sentence structure—you can fill in the blank . . .] and they don’t do it.” Just like I’ve heard tennis pros tell me over and over again to step into the ball, sometimes it doesn’t happen. Not because I don’t know it. Not because I don’t want to. Not because I’m not trying. It’s just that sometimes there are too many things to think of!

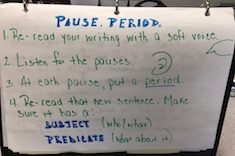

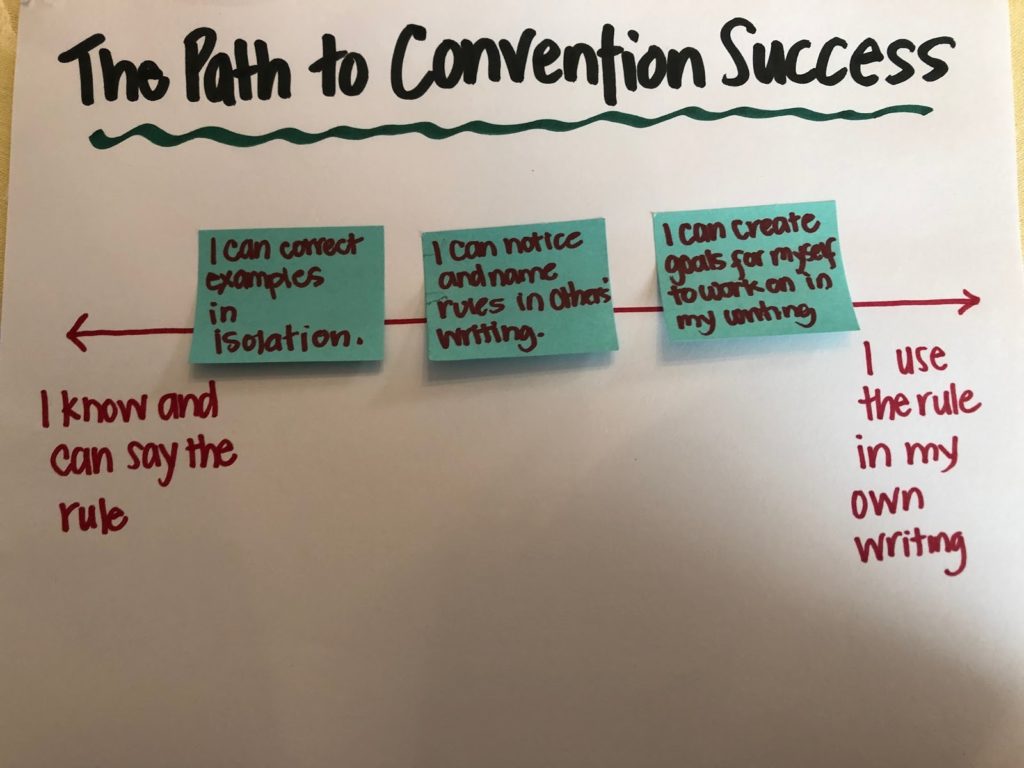

To respond to some teachers about the convention conundrum (the continual issue of I’ve taught it but they haven’t learned it), I created the graphic below:

This graphic allows us to talk about the stages students are in as they are learning new concepts within the overall category of conventions. Maybe they know and can say the rule, “A sentence has someone or something thinking or being or doing something. We put a punctuation mark at the end.” Or maybe they are able to notice and name rules in other people’s writing. Somehow it is much easier for almost everyone to spot and correct mistakes that aren’t their own! As they get closer to mastery, students may be able to recognize what they need to do as convention users and set goals for themselves.

Having this graphic allowed us to have more meaningful conversations about how we could provide the most effective instruction since students in different stages along the continuum benefit from different activities and lessons.

When Students Can Do the Work in Isolation

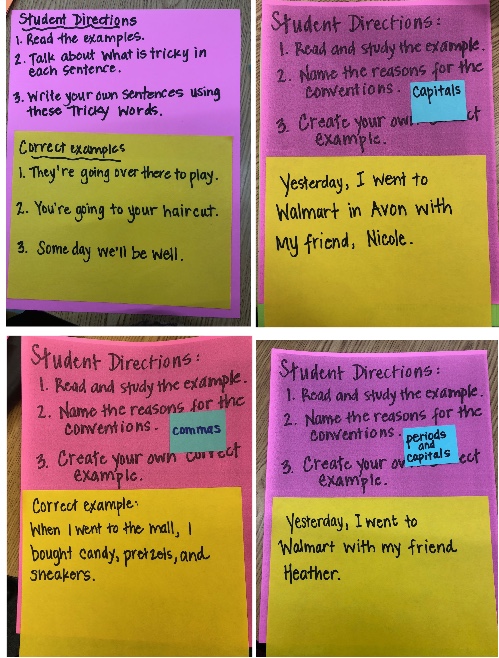

One of my favorite ways to work with students who are on the continuum but still working on mastery is to set up stations for them to notice a skill, name it, and then practice it. Although many teachers gravitate toward worksheets or online drills and activities in this stage, I find great benefit in asking students to create something of their own.

If you look at the directions on my pink cards, you’ll see that I have set up convention-oriented activities to be independent and targeted, challenging students to move up the ladder of cognitive work, with creating toward the top of that ladder.

The cards I have shared above are examples. When you notice patterns of mistakes in your students’ writing, you can use them to inspire your own practice center. For example, if students are consistently struggling with the correct use of quotation marks (which is common!), then set up a center where the quotation marks are used correctly and they have to create their own example.

Please note: I don’t ever show students incorrect examples, at least not on purpose. I want them to remember the correct way to use conventions, and not just that they are complicated or tricky.

When Students Can Correct the Work of Others

Even when my lesson is about structure or development, there are students who love to point out punctuation mistakes or spelling errors, although they often have plenty of conventions to correct in their own writing. If they can see it in other people’s writing, it’s hard to understand why they can’t make the leap and see the mistakes in their own writing, but for whatever reason, that’s tough for many learners.

One way to handle these students is to make sure they explicitly show the evidence of their correct work. “Show me” is a playful activity that students can play in partnerships. If there’s a list of expected conventions (and there should be), then one partner can select a given skill and ask first if it’s done correctly, and then ask for it to be shown or pointed out. The conversation could go something like this:

Partner A: Do you have all of your names capitalized?

Partner B: Yes!

Partner A: Show me.

At that point, Partner A has to go into their writing and show Partner B where they have used correct capitalization for names.

An important aspect of this activity is that both partners are engaged in the language and expectations of the skills. Many times, this repeated exposure helps shift the skill from approximation toward automaticity, which is what we want to have happen. Just like in tennis, at some point we shouldn’t have to think about taking small steps toward the ball—we just do it.

When Students Can Set Goals for Themselves

Not everyone needs to work on the same skills all the time. It empowers students to make decisions about the specific skills they are going to work on and hold themselves accountable for. If a student always capitalizes the first letter of a sentence, then there’s no need for that aspect of capitalization to be on their checklist. But maybe they know that titles of movies and books should be capitalized but forget to do it in their own writing. In that case, movie and book titles become a goal for capitalization.

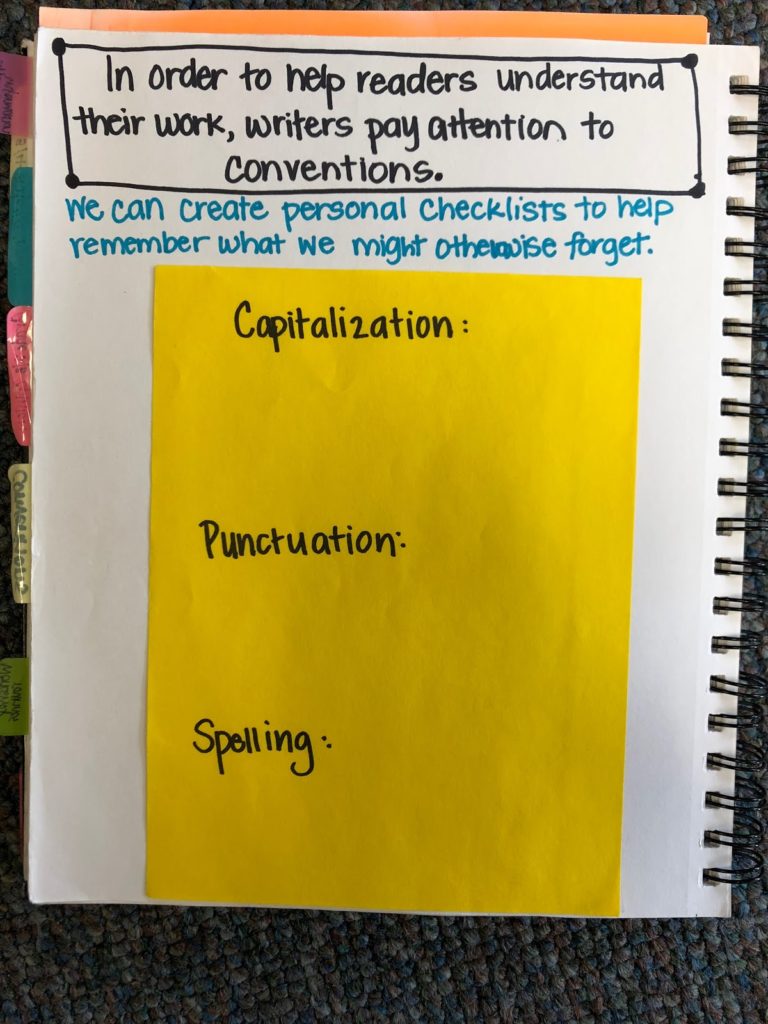

I like dividing conventions into categories to make them feel a little less overwhelming. Students can fill in their own checklist or goal sheet that encourages self-efficacy and personal responsibility for learning. As they master skills, they can cross them off or create new pages for themselves.

When I am practicing tennis regularly, I have a better and better sense of what I’m doing well, what I need to work on, and how I can make the most progress. I don’t need Kurt to tell me I’m not stepping in—I can figure that out myself, and I can make my own adjustment. Just like within my tennis life, when we know where students are functioning along a continuum, we can understand better how to move them forward in ways that have the most potential for retention and transfer.