Fifth-grade teacher Pam was encouraged by her principal to transition from mostly whole-group instruction to include more small-group instruction, especially in the area of reading. The previous year she’d used a one-minute reading probe to sort her students into groups using leveled books. A reading inventory, running records, and classroom observations helped us group the students this year. We’d also moved the conversation from guided reading only, to guiding readers with self-selected independent texts with a strategy focus. In order to plan, we’d looked at a variety of strategy categories that successful readers need. Now we were at the point where we needed to structure the group sessions.

Predictable Structures and Routines

One of Jennifer Serravallo’s tenets in her book Teaching Reading in Small Groups is that small-group instruction should follow predictable structures and routines. She sees her small-group work in four parts: connect and compliment, teach, engage, and link. My colleague Amanda Adrian uses the structure of name it (the strategy), model it (what it should look and sound like), and practice it (opportunities to apply the strategy on the spot), which is her adaptation from The Daily Five

by Gail Boushey and Joan Moser.

My own structure is three parts: what, so what, and now what. The what is stating why the students are in the group and the objective. Then the so what is my demonstration if necessary of why that strategy makes one a better reader or writer. Finally, the now what is releasing the strategy to the students and discussing how it will be practiced.

Jennifer uses four verbs, Amanda uses three verbs + it, and I use three forms of what. All three have in common many aspects of good instruction:

- Including an explicit introduction, “Today we are going to…”

- Explaining this strategy has been chosen specifically for that student/s, not just because it’s up on the curriculum queue.

- Modeling the strategy if needed or appropriate.

- Naming, labeling or inviting the kids to say what the strategy looks like/sounds like.

- Releasing the strategy to the student and guides in the moment.

- Concluding with the student summarizing the strategy, why it’s important as a reader and a plan to check in later.

Provide the Structure or Co-create?

In my fifth year as an instructional coach, I’m thoughtful about the learning styles of each of the unique educators I work with. Andrea is a third-grade teacher who wants me to spell it out for her. She’s said to me, “I have no need to be creative. Other people have figured out what works; I just want to know what it is and how to do it.” For Andrea, I would share an excerpt from Jennifer’s book that we could read together, highlighting the four components of small-group instruction and then transferring them to a planning sheet.

On the other hand, Caroline is constantly modifying things even before she teaches them for the first time to her fourth graders. She’ll say, “I think I would do that first because that’s more like our routine” or “I’ll remember it better if I call it something different.” With Caroline, I’d share the common traits of high-quality small-group conferring, and co-create the components with her. It doesn’t matter so much what we call the structures for our planning purposes. It does matter that it means something to the teacher so it can become a routine.

Pam, a fifth-grade teacher, was more like Caroline, and she jotted notes with chronological transitions that made sense to her. We co-planned the small groups she wanted to observe. Her notes read:

“First Heather will let the kids know why we are pulling the group and what the learning objective is.

“Then she’s going to model what it looks like.

“Next she’ll let them do it.

“Finally she’s going to ask them what they learned and make a plan to apply it.”

Modeling Small-Group Instruction

I often encourage the teachers I work with to give me their perplexing students to meet with first. These opportunities open up rich discussions. Pam was grateful that I was willing to start with the group that was not engaged with reading.

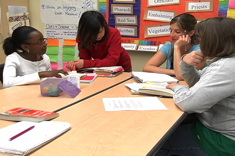

We called Chase, Isabel, and Emerson to the table. Pam was going to take notes on my language next to the first, then, next, and finally planning notes she’d written. Here is some talk from our small-group conference:

“Thanks for coming back quickly so we can get started. You are all here in a group because you said during our conversation about reading that you don’t see yourselves as readers. We appreciated your honesty, and you telling us that you aren’t crazy about the books you read—that reading is more of chore than something you enjoy. Our objective for the next 10 minutes is that you are going to leave this table with a book you are excited about that you’ll be able to read for the next half hour this morning and then report back. Sound good?”

At this point the kids were leaning forward and eyeing the books I had stacked in front of them.

“Chase, you told us that you liked comedy a lot. So I have two books that might appeal to you. Guys Write for Guys Read and Guys Read: Funny Business

. Both are collections edited by Jon Scieszka.” I read the table of contents and a paragraph from one of the pieces by Jack Gantos. “The cool thing about this book is it’s made up of short stories so you could read the ones that appeal to you and skip the ones that don’t.

“Another book that is made up of short stories, or in this case, letters, is Dear Bully: Seventy Authors Tell Their Stories. Isabel, this made me think of you because you like nonfiction.” I mentioned a couple of the authors I knew who wrote pieces for the collection. Mo Willems has a piece called “Bullies for Me” and there was a catchy title that I knew would appeal to Isabel “Who Gives the Popular People Power? Who???”

“Emerson, you said that you preferred nonfiction.” I opened a book to eye-catching spreads about spies, and another about fast cars. “You just saw me read the back, look at the table of contents, and read a small part. I’d like you to do the same thing now, so reach for the book that—”

Pam and I laughed as the kids lunged for the books they wanted to preview. After a minute I moved quietly next to each child and asked what they were thinking. Isabel said, “I think I’m really going to like this bully book because it seems like mature, but I don’t have to read the whole thing.” We pulled back together as they held on tight to their chosen books.

“Why did we gather today?” I asked.

“Because we all didn’t really like the books we were reading.”

“What is a strategy to help with that?”

“You guys thought about what we liked and gave us some suggestions.”

“True, and in the future, we are going to teach you how to think about the genres you like, the authors you like, and the types of books you like to read so you can create your own pile.

“What did you do to preview?”

“We read the back, the table of whatever—”

“Contents,” I said.

“Have you ever done that before?” All three kids shook their heads.

“And what is your job now?”

“To go read them,” Chase said.

“And?” I raised my eyebrows.

“Be crazy about them,” Emerson joked, dramatically pulling the book to his chest.

“And I’m going to check in with you in 30 minutes,” Pam said.

What’s Next?

We looked back at Pam’s notes. Next to each step she’d recorded words and phrases I’d used.

“I noticed that you previewed each book quickly, but you connected why we’d picked them to what we knew about kids as readers or what they were like. The table of contents was a really good place to spend time because it connected kids to authors they’ve known—even from picture books—and the titles were catchy. I wouldn’t have thought that something like this is a legitimate small-group topic, or think about the structure of it. But now I see it’s not just legitimate, but necessary if I’m going to get those kids engaged in the other strategies we’ve talked about.”

Pam emailed me later that day to let me know that Chase had asked—for the first time ever—if he could read when he was done with his math. While at first she had observed him jumping around from short story to short story, he soon flipped to the front of the book and was reading them all, and smirking from time to time.