The past year has been a steep learning curve for Kate. After nine years in a fourth-grade classroom, she moved to a literacy interventionist position, in which she pulls struggling readers who are at least two reading levels below the grade-level benchmark to provide daily reading support. The groups range in size from one student to four, and include first, second, and third graders. Most of the groups meet for 20 minutes, and two meet for 30 minutes. The groups follow a guided reading structure.

Although working with struggling readers isn’t new to us, the population (more than 85 percent Hispanic, and the majority of that ELLs) is new, and so presents new challenges. Across the reading levels and grade levels, the students seem to lack confidence in talking about their reading—both literally and inferentially—and sometimes are not even sure how to start telling what they just read.

If we were in the classroom, we would use daily read alouds to model and support talking and thinking about texts. The way my groups are structured doesn’t allow for daily read aloud, though, because the students need to have books in their hands and be reading for most of our time together.

We’ve settled on a weekly goal for each group, allowing the goal to spill into the following week or two if necessary, based on how students are doing. That way, we focus on one strategy to support their talking about reading multiple times across the week so that, ideally, there’s improvement in their talk and familiarity with the strategy by the end of the week. These are some of the goals we set for groups:

- Literal retelling. (We started with fiction because we thought that was more familiar to students, and then introduced retelling an informational text by teaching what you learned.)

- Talking about ideas

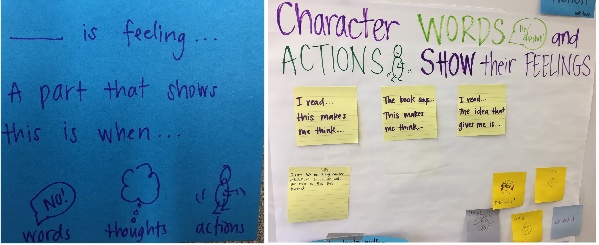

- Supporting ideas about character feelings with evidence. (The type of evidence varied, depending on the reading levels of each group. For levels K and below, we focused on both words and pictures as supportive of our ideas. For levels L and above, pictures were less supportive, and the evidence had to be found in the words of the text.)

- Supporting ideas about character traits with evidence

- Identifying lessons in texts

Retelling Events with Hands

Rehearse across the week—We began with a chart with a hand and phrases to start talking about the literal events of a story on each finger. We modeled retelling a story that was familiar to the students, holding up another finger as we retold five important events across the story so that by the end of my retell, all five fingers were up.

Students held their fingers up as we modeled. After the modeling, students practiced in pairs or alternating with the teacher, using the story that we had read that day or the day before. We repeated this across the week until they seemed comfortable with the literal retelling of a story.

Build in more components: characters, setting, problem, lesson. Once the students were comfortable with telling events of the story in order, I added some components to help lift the level of their retelling. The components we focused on were using character names, and adding the setting, the problem, and the lesson. We added one at a time, gradually, across a few weeks. I added them to the chart in the middle of the hand on sticky notes (some are pictured above) so I could point to them and remind students to use them during their retell.

Scaffolds for Thinking, Talking, and Writing

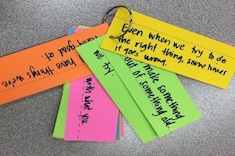

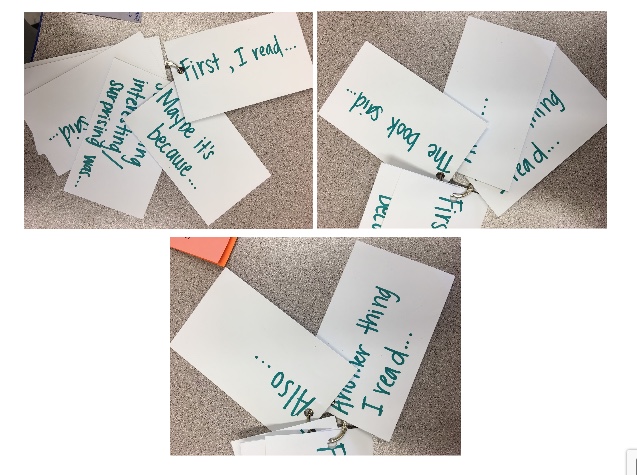

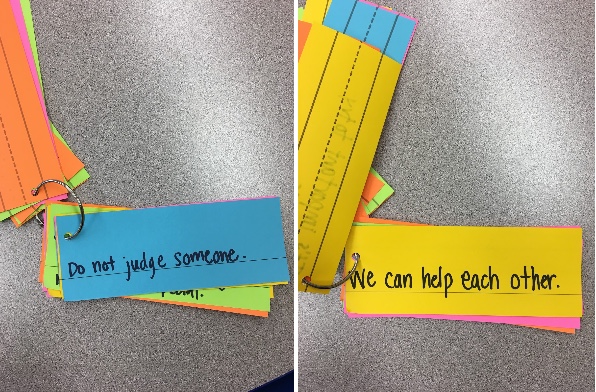

Phrases for literal retelling on a ring. For a student who struggled with retelling during a running record, we made a ring with phrases for her to use anytime she talks about her books. During the running record, she answered questions accurately, but she wasn’t able to get herself started talking independently about her reading. It was clear she had an understanding of the text, because she could answer questions with significant detail, but she was having difficulty retrieving what she had read.

The phrases we made on note cards are similar to phrases on the retelling-across-our-hands charts, except they don’t set the student up to retell a story sequentially. Rather, they’re more open-ended phrases so the student can flip through and choose which ones are appropriate for her reading. There was almost immediate improvement in her talking independently about her reading once she started using the phrases. On a running record only a week later, she independently took the phrases out and confidently flipped through them, using them to talk about what she had read.

We commented on how some of the phrases were ones she had already memorized, and that she can use them anytime she’s thinking, talking, or writing about her reading.

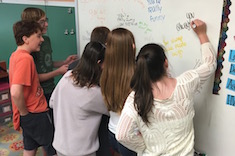

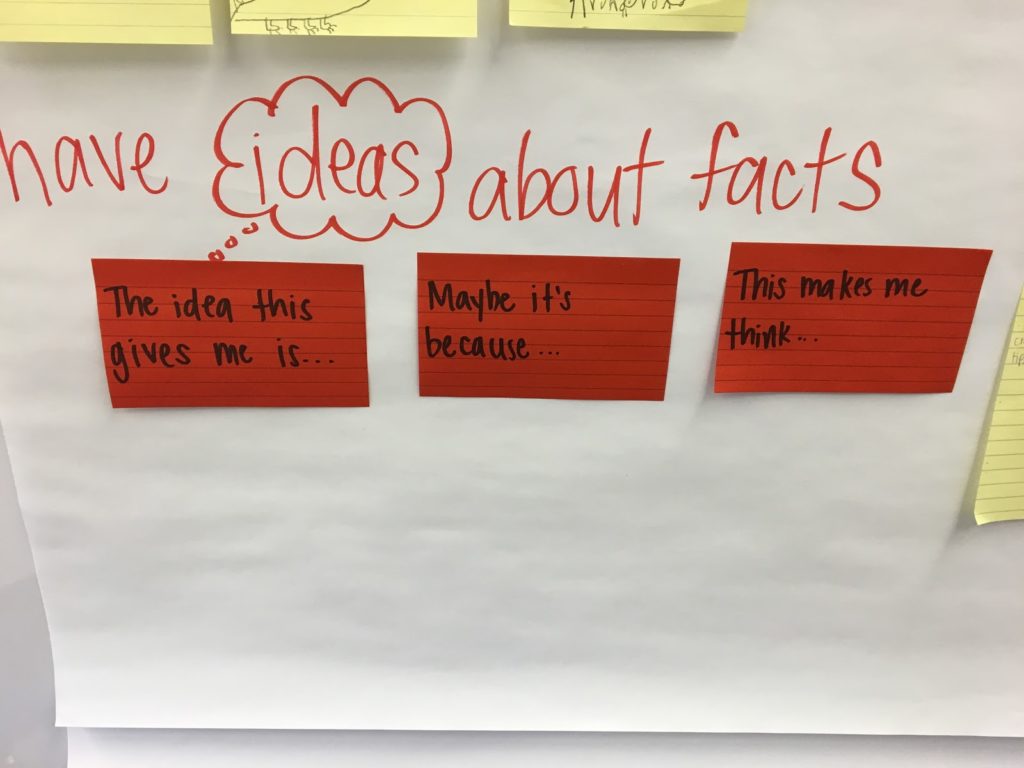

Phrases for talking about ideas—A chart with some sentence starters that all lead students from talking about events to ideas has been helpful to refer to during conferences or discussions as a group. When a student retells an important event from the story, we might say, “What does that make you think? Choose a phrase,” and point to the chart. Similarly, we might just answer a student’s retell of an event with one of the phrases from the chart, prompting them to repeat the phrase and then try to finish it with an idea.

Once we began this work in fiction, we tried it in information texts, using some similar phrases:

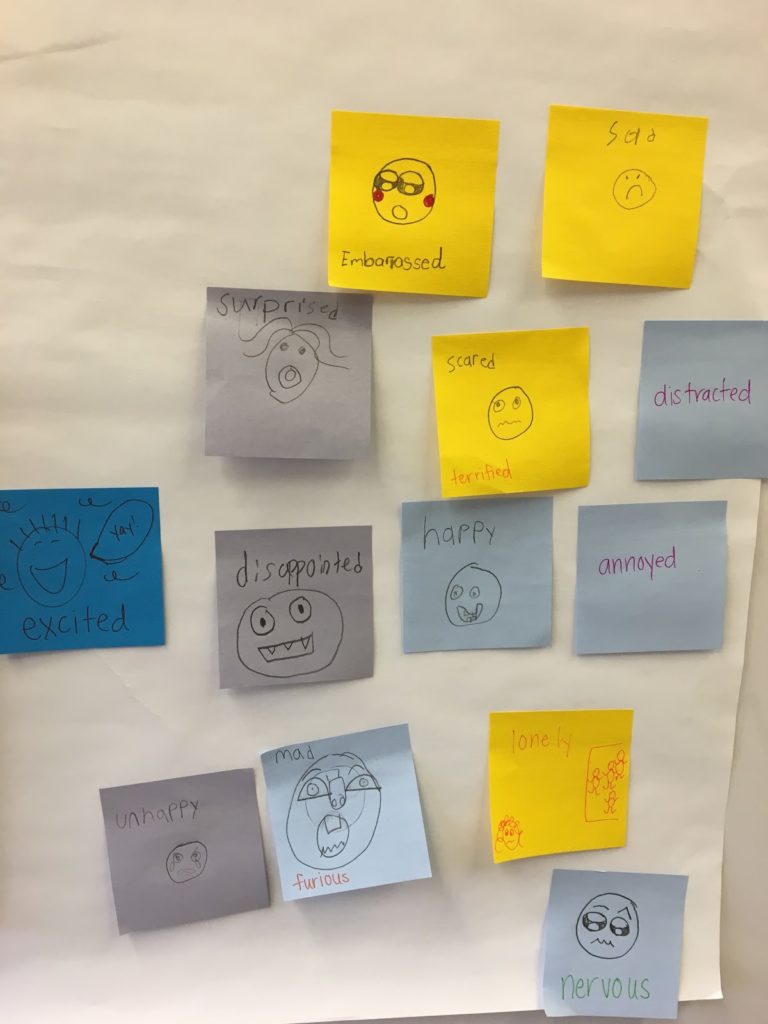

Vocabulary for feelings and traits with pictures—Anytime a student mentioned an idea about a character feeling, I’d give him a sticky note and help him write the feeling down. The student would add a picture to show the feeling and then stick it to a chart. The sticky notes became a resource for students to use when they were talking about their ideas about character feelings. Students later worked to sort the feelings into three columns on the chart, marked with a +, +/-, and -, to show feelings that were positive, negative, and neither positive nor negative or either, depending on the circumstances. Interacting with the vocabulary and organizing it in this way provided an additional support for students and an opportunity to think and talk around the words.

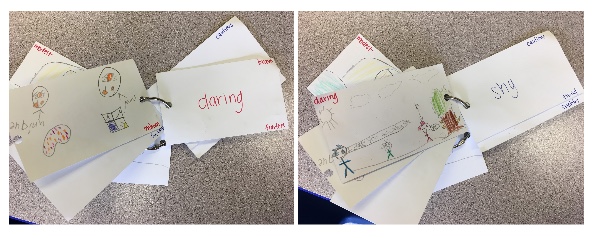

As we read through stories and talked about character traits, we also made word cards with the traits in the middle and synonyms in the corner. Students helped illustrate the trait on the back, and we’d refer to them as we talked and wrote about our ideas about characters.

Also on the chart were phrases to help them name an idea with evidence. We tried two different versions of the phrases—some starting with the evidence and others starting with the idea—so that students found one that they were successful with using.

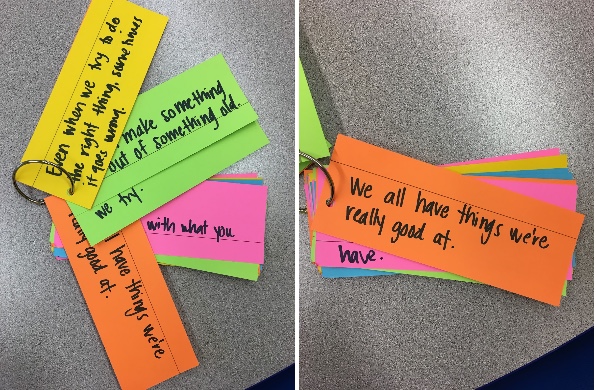

Ring with lessons, messages, and themes—As students read stories and discussed lessons and messages from the stories, we wrote them down on sentence strips and added them to a ring. Since many lessons are true across different texts, students struggling with naming a lesson from the story could flip through the sentence strips on the ring and talk about which lessons fit with the new story we had read and why.

In this way, the ring became a collection of lessons we’ve seen and discussed in texts, but also a resource to support students in thinking and talking about lessons in new books.

The reality is that many of these goals were revisited over and over again across more than two weeks, and it didn’t work as neatly as focusing on one goal each week. Reading requires many skills at once, after all, and so rather than having one as a singular focus for each week, we often ended up doing work across these goals. For students like the ones we’re working with—struggling with reading or learning to read while at the same time learning the language—our ideas about what we’ll accomplish may have been overly ambitious.

We’re learning that repeated exposure to and use of academic language is an essential part of language development. After spending a few weeks on retelling using the phrases, students were more comfortable and confident when they talked about their reading. The phrases also became more internalized, which allows for the scaffolds that the charts provide to be removed so that students begin to feel what it’s like to talk about their reading more independently.