When I was in junior high way back in the day, the biggest and most important papers we had to write about the books we read all focused on one thing: theme. I hated writing these papers. They killed my love of reading in general and my love for the book I had just finished in particular, because my teachers always let us know that there was one theme for every book: the correct, teacher-divined and dictated one. You could slog away for days writing a beautifully thought-out and paragraphed essay following the teacher-ordained format exactly, but . . . get the theme “wrong” and there went the grade.

My experience has made me want to give my students much more freedom in thinking through and formulating ideas about theme in the books they are reading. But too much freedom can lead to a great deal of confusion. After all, theme is a complicated idea, one that takes a lot of careful thinking and theorizing to arrive at, whether one is reading a picture book like Margaret Wild’s Fox or a middle-grade novel like Sara Pennypacker’s Pax. I think my colleague Julieanne Harmatz said it best when she described theme this way:

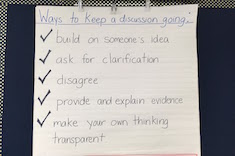

In my sixth-grade class, we approach the process of thinking about theme by asking the following questions:

Rather than focus on a single word to describe theme, which can lead to cliches (for example, “Honesty is always the best policy”), or cliches that can lead to formulaic thinking (such as “Don’t judge a book by its cover”), I ask my students to consider the following universal themes that Cornelius Minor shared with us during a workshop at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project:

These themes are both thoughtful and general. They give students something meaty to build their thinking around as they practice the tricky business of evidence gathering in their texts. We use these universal themes as ideas to begin with, even as we recognize that there might be other topics to consider extending out into thematic statements:

I find it helpful to use a visual to show students that literary elements form the building blocks of theme, so they know where to look for clues as they begin forming their theories:

And then, of course, we practice with read-alouds. Here’s what we came up with after reading Those Shoes by Maribeth Boelts:

Practicing with a few read-alouds allows students the freedom to experiment with taking a topic from the idea bank and stretching it out into a well-developed thematic statement, or choosing one of the universal themes. Both can be supported with evidence from the text.

Arriving at conclusions about the theme of a story is hard work involving many layers of thinking, as evidenced by this definition from the Common Core Standards:

Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text.

Students need an organized approach to access this deep thinking, some scaffolds to stand on, and practice through read-alouds and class discussion. Bit by bit, they get to the heart of determining theme, which deeply enriches their reading lives forever after.