In a second-grade classroom reading workshop, completely remote this year, students gather around the virtual hearth to read independently. The teacher, Mrs. H, has set students up to stop and jot their questions and exclamations on sticky notes as they read while she confers with pairs or small groups in breakout rooms.

As a coach, I popped in and out of virtual spaces to listen in on student talk midway through reading time. The depth and breadth of their comments astounded me.

“Brown and Black people are not always treated nicely,” I overheard one child say. “But that doesn’t mean be mean to white people.”

“This book has an equal number of white people and people of color,” said another student.

“I noticed the white characters are the main ones and if there’s a Black character, that person is a sidekick,” a young boy said, “not usually the main dude.”

Although these lines were collected from various visits, what strikes me is the students’ abilities to name plainly what adults often dance around. I find myself thinking,

How do teachers cultivate inquisitive stances in students?

How do educators support students in building muscles of informed empathy, rather than sympathy?

Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings, in a recent talk on justice in education, made plain the difference between breeding a condolence mindset when thinking about people in different walks of life and understanding what others are experiencing. Building an inquisitive stance and informed empathy in students is critical to a robust literacy program, but more importantly, to cultivating citizens of the world. By asking students to imagine scenarios not in their typical worldviews, they are offered windows through which to see more. Dr. Rudine Sims Bishop, who coined the concept of windows, mirrors, and sliding doors in the 1990s, further explains that white children need to see more than white narratives because of the danger of otherwise developing an exaggerated sense of self.

Adults might wriggle in discomfort and cringe at unpracticed conversations, but young children learn easily how to discuss matters of race, representation, and inequity without the nuances adults worry about. In the classroom where I captured the conversations above, the teacher attributes part of her students’ reflection, wonderings, and noticings about diversity and injustice to thoughtful mentor texts—ones that exalt people from all walks of life.

Although equity work and peeling back the layers of injustice is an ongoing journey that requires turning a critical lens toward all of our curricular materials, systems, and school practices, one small step is to grow curious minds, particularly around rich, inclusive picture-book read alouds, and allowing space for students to grapple with, talk about, and learn from the pages. There is no single Band-Aid approach. There is no single social justice curriculum. Instead, there is purposeful, open conversation-building around positive portrayals of diverse cultures.

When using your own read alouds, use suggested booklists from reputable organizations and mentors, and be sure to read the entire text before sharing it with students. Think across your year so that students aren’t getting a single text swap or solely stories of trauma and hardship of Black and Brown people, but instead, a more comprehensive and complete picture of all humanity.

The following three picture books are gorgeously varied stories written by people of color (#OwnVoices) that clearly affirm cultures beyond the typically dominant Eurocentric narrative. Though each picture book is in a different genre—fiction, wordless fiction, and nonfiction—the questions transcend a single narrative style. The questions embedded below each text are suggestions that support student exploration.

Thank You, Omu! by Oge Mora

Thank You, Omu! by Oge Mora is a lovely, nourishing story about an older woman concocting a delicious stew that ends up feeding the entire town, until she herself doesn’t have any food for her own evening meal. But the community takes care of her and ends up celebrating communal friendship as a result. Guiding questions like the ones below support skill-building around informed empathy, ensuring that students see Black joy on the pages—not just stories of slavery and civil rights struggles. In moving beyond a sliced trope of diversity and allowing students to talk about positive, character-building narratives with inclusivity of voice, teachers can build the muscle in students to have frank conversations about injustice. Depending on grade level, students might stop and jot or draw their thoughts about these questions ahead of talk time.

- How does the character take care of others?

- What meals have you shared with others you love?

- How does the community take care of one another?

- In what ways does the community thank and show appreciation for each other?

Wallpaper by Thao Lam

Wallpaper by Thao Lam centers on a little girl who is new to her neighborhood and hears children playing outside. She’s too shy to introduce herself, so she sits alone in her new room and peels back the wallpaper—only to discover furry monsters and an entire imagined world behind her walls. It’s a wordless tale told in collage images about being brave. An expansive definition of reading—telling a story by images alone—supports students’ confident storytelling abilities while reading this book, too. When teachers read texts without words by telling the story across pages in reading pictures, students build confidence to do the same.

Again, the questions and prompts below cultivate space for students to make connections to a character who might not necessarily look like them but feels similar emotions.

- Tell about a time you felt nervous or embarrassed.

- What might the little girl be fearful about?

- Why do you think the little girl feels uncomfortable at the beginning of the story?

- How do you think the girl becomes more brave as the story progresses?

- What kinds of experiences have made you grow braver?

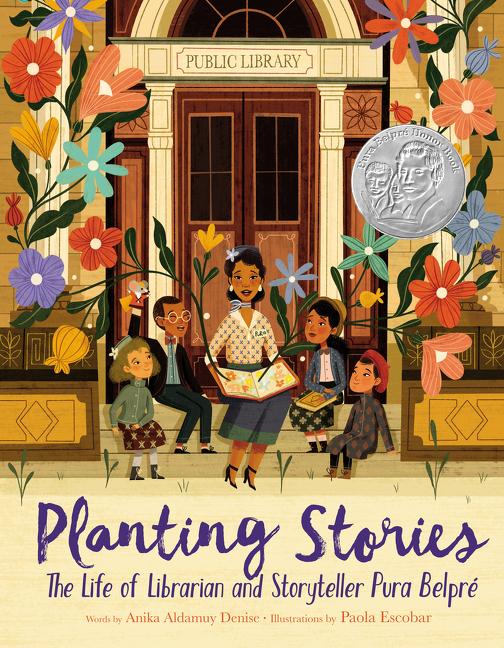

Planting Stories: The Life of Librarian and Storyteller Pura Belpre by Anika Aldamuy Denise

Planting Stories: The Life of Librarian and Storyteller Pura Belpre by Anika Aldamuy Denise is an inspirational story about the first Puerto Rican librarian in New York City and includes beautifully fluid translanguaging—seamlessly peppering in Spanish words—and nonfiction facts that exalt Latinx identities of intellect. Pura Belpre brought Spanish-language stories to the library when there weren’t any, and shared Latinx folktales when they weren’t commonly known. She knew then, before her passing in 1982, that representation matters. It is important to use nonfiction picture books with positive portrayals of people of color in classrooms to ensure students see the varied and deep contributions that all kinds of people have made to society. Every story matters.

The questions below might prove to be useful guides when including other nonfiction picture books, in asking students to frame contributions as gifts and think beyond the pages to ways we can make a difference.

- How can we be change makers?

- How did Pura Belpre make change in her circle of influence?

- What was important to Pura Belpre, and how did she share her ideas with others?

- What do you feel is important to share with others?

- What did you learn about Latinx folktales?

- What was Pura Belpre’s legacy? What do you want your legacy to be?

Purposefully selected picture books not only are fun to read and look at with students but also provide windows into new cultures. When such books are chosen wisely, with general guiding questions that teach informed empathy, students begin to grow their abilities to look with criticality at text beyond classroom walls, thus shaping the ways they see the world. When teachers make space for students to talk about texts openly, they need not worry too much about directing the conversation (barring hurtful comments, which must be handled swiftly). Children make sense of the world by observing, absorbing, and creating, crafting their own conversations and realizations toward a more thorough understanding of humanity.

As teachers of literacy, we are responsible for supporting student comprehension in reading and writing in unique and meaningful ways that speak to widely varied ways of life. To cultivate students with informed empathy—those who are curious and genuinely interested in learning more about the world around them—we must expose all students to thoughtful, inclusive texts. These picture books provide a start.