I am a big fan of Yotam Ottolenghi’s cookbooks. I love the unique flavors in his recipes and the way he incorporates so many vegetables into each dish. On the weekends, I look through Ottolenghi’s recipes and choose the ones I want to make. Like other cookbooks, his recipes list the ingredients I need and the steps I will complete, but I still need to do a bit of planning before I begin. I collect the ingredients and make decisions about the type of bowls and cooking utensils I will use. As I gather the items, I picture myself following the steps in the recipe, a process that helps me remember what I need to do.

When students begin a project, the process is no different. They also need to think,

What am I trying to accomplish?

What tools do I need right now? and

How will I use these tools?

Unfortunately, sometimes students don’t get this opportunity. Teachers have already collected the items, so everything is all set. But I wonder how many students look at the neat pile, basket, or organized folder of resources and wonder, What is all this stuff for?

I know. I know. We have explained and modeled how to use these resources, but that isn’t the same as collecting the supplies and thinking through the steps on your own. When we hand the resources to students, it is a little like watching a cooking show and then trying to make the recipe from memory. It is tricky, even for the best cooks.

Book clubs are one social structure in the classroom where students can take the lead and collect what they need. Besides choosing which text to read, here are a few ways to give students ownership when they begin book clubs.

How will you record your thinking during book club meetings?

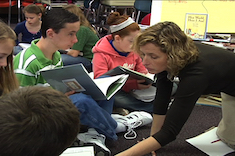

Students spend most of their time in book clubs talking about the texts they read, but I expect students to write twice during each book club meeting:

- Students come to the book club with an idea they want to discuss. They write the idea down so the group can see everyone’s ideas before the conversation begins.

- After the group has finished their discussion, students write down new insights or ideas they have uncovered.

These are the steps students need to complete, just like the steps I need to follow in Ottolenghi’s recipes. But we can give students some decision-making power about how they record their ideas. Do they want to record their thoughts in a notebook, on chart paper, or in a Google Doc? When students choose where to record, they are more apt to remember to do it.

What mark-making tools do you want to use?

When students arrive at the book club, we want them to be able to record their ideas simultaneously. Therefore, each person in the group needs a mark-making tool or digital device. When the kids decide what they need, collect them, and choose where to put them so they are available for every book club meeting, the responsibility for materials shifts from the teacher to the students.

What anchor charts do you need?

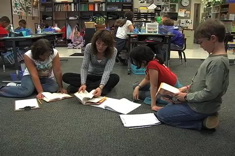

Charts of book club norms—lists of ways to begin conversations, build on someone else’s ideas, or disagree respectfully—can be helpful. However, these charts are useful only if students use them. Instead of handing out smaller versions of our classroom anchor charts, book club members can create what they need.

Each group reviews the classroom anchor charts and decides which prompts will support their work and how they want them displayed. Do they want to make a chart with the most helpful prompts on chart paper? Or might they want to put each prompt on an index card and lay out the cards before they begin a conversation? Some groups might want each member to have an individual chart they can have out in front of them.

I encourage groups to create charts that will help them lift the level of their conversations—and not list prompts they already use. Students grab chart paper, blank paper, blue books, or digital devices and make what they need. Once they finish, the group decides where these materials will be stored and how they will display them during book club conversations.

Putting students in charge of the decision-making process has changed the way they approach book clubs. Instead of some students being unsure what to do, most understand the process because they helped create it. I see more students participating—whether that means laying out the anchor charts, making sure they record ideas at the end of a book club meeting, or using the new language to lift the quality of the conversation. When students have a voice in the tools they use, just like when I decide what to cook and which materials around my kitchen I will use, we increase student engagement and agency.